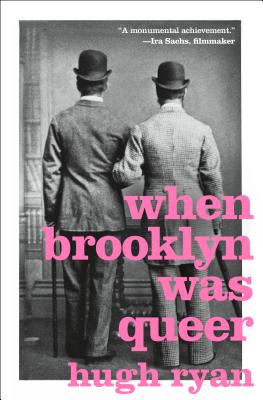

When Brooklyn Was Queer

When Brooklyn Was Queer

by Hugh Ryan

St. Martin’s Press. 320 pages, $29.99

IN 1965, as a senior attending a Jesuit high school in Manhattan, I told the student counselor that I thought I had a calling to the priesthood. Then I told him the bad news: I had strong homosexual urges and had acted upon them several times. He listened sympathetically, expressing no condemnation, and volunteered to arrange an appointment with a Jesuit psychologist who would determine if these desires would be a barrier to my entering seminary.

The psychologist’s office was in Brooklyn Heights and, Bronx boy that I was, the trip there seemed like a journey to a foreign land. After interviewing me and administering a Rorschach test, the shrink suggested I take a walk in the neighborhood while he evaluated the test. Leaving his office, I soon found myself on the Promenade. The view of Manhattan was magnificent, but that wasn’t what captured my attention. Instead, I noticed a stream of men strolling back and forth and eyeing each other, including me. Unlike Times Square, a cruising area where a few gay men were crowded among hundreds of other pedestrians, on the Promenade they predominated. That walk made me realize that my sexual desires were not going away and that life as a priestly servant of God was a fantasy never to be realized.

Little did I grasp that I had stumbled upon one of the last remaining sites from a century-long history of queer life in Brooklyn. But that is one of the many things I learned in reading Hugh Ryan’s immensely absorbing When Brooklyn Was Queer. Stretching from the Brooklyn that helped produce Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in the 1850s to the post-World War II decades when Brooklyn’s queer world seemed to disintegrate, the book brings vividly to life a story largely erased and forgotten.

History is above all a study of change, and Ryan does an excellent job of moving through several eras of the past, each with distinguishing characteristics. Ryan describes the mid-19th century—the decades of Whitman in Brooklyn—as a time when some individuals were coming to recognize themselves as queer. In the decades bordering the start of the 20th century, queer folk began to discover each other more easily and to learn that they were not the only ones. In the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s, Ryan observes that it was “increasingly possible to live a queer life.” But that growing visibility and collective existence was also making it easier to get into trouble for it. An alliance formed among police, doctors, and moral reformers who were interested in identifying and punishing sexual outlaws. The disruptions of World War II, when young men and women by the millions were leaving their families and hometowns to join the military or work in defense industries, created a few years in which a gay world seemed to flourish. But then, in the postwar decades, a century of queer life in Brooklyn began to unravel. With LGBT people seen as threats to the nation, aggressive attacks by the state became the norm, while housing policies and highway construction disrupted Brooklyn’s queer urban spaces. By the time of the Stonewall rebellion and the birth of gay liberation in Manhattan, Brooklyn’s queer life—except perhaps for the cruising in Brooklyn Heights—had faded almost into nothing.

Even as Ryan outlines distinctive eras with characteristics of their own, he also identifies some common threads in this century-long timespan. The waterfront, especially after the opening of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, was a major site for finding queer sex. Several occupations associated with the waterfront—sailor, sex worker, entertainer, artist/writer, female factory worker—had queer connotations. For many decades, working-class bachelor subcultures with their rooming houses and saloons allowed gay males to find willing sex partners. The nightlife that spawned entertainment districts along the waterfront, like Coney Island, supported gender-bending impersonators, both male and female, and thus created a space that allowed queer people to gather and find one another in safety. And, through all these decades, writers keep surfacing who were living in Brooklyn and, through their work, suggested the queer life that Brooklyn sustained. From Walt Whitman and Mary Hallock Foote in the 19th century to Hart Crane, W.H. Auden, and Marianne Moore in the 20th, Ryan makes use of their writings, both published and unpublished, to reconstruct a previously unrecognized social history.

I think what most impressed me about When Brooklyn Was Queer was the creativity that Ryan displays in bringing a century of history to life despite the sometimes limited documentary trail. For every period he covers, he uses a broad range of source material that offers a three-dimensional picture of Brooklyn life—its streets, its commercial life, the neighborhoods where same-sex activity occurred. Then, when he does offer the words of someone we might today describe as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender, I was able to imagine them in their surroundings, the stuff of everyday life fleshed out for me.

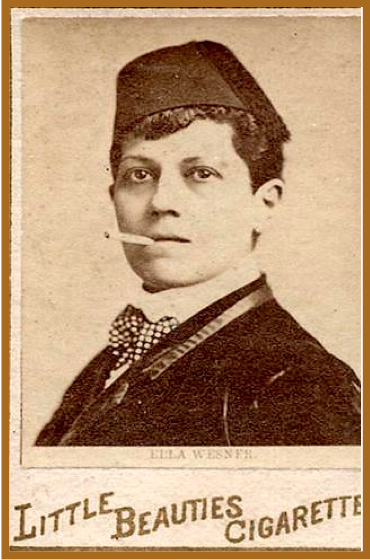

Some characters are unforgettable. There is Ella Wesner, a male impersonator who performed regularly in the post-Civil War era and whose surprisingly public love affair with Josie Mansfield, an actress, was covered by the press—“a singular fancy,” according to one paper. Or Thomas Painter, who proved to be one of Alfred Kinsey’s most voluminous correspondents, filling Kinsey in on seemingly every detail of queer life in Brooklyn that he possessed. Or Rusty Brown, a working-class lesbian who recounted how the World War II years were gloriously liberating, but then how “our world started to collapse” once the war was over.

Inevitably in a history that covers such a long span of time, Ryan has to cope with the limitations imposed by his sources. Much of his material comes from individuals who were writers. They, of course, were the most likely to leave behind a documentary trail; they also were often the most able and likely to leave Brooklyn behind. Ryan does a good job of trying to move outward from their words and experiences, but it left me wanting to know more about the experience of those countless souls who never left, whose working-class lives were firmly implanted in Brooklyn. While When Brooklyn Was Queer is an invaluable resource, I hope there will be future accounts that dig even deeper. In the meantime, Ryan has offered us a fascinating, surprising, and engrossing history of that place across the river from Manhattan, thus displacing the all-too-common misperception in LGBT historical writing that New York is Manhattan.

John D’Emilio, professor emeritus at the U. of Illinois-Chicago, is the author ofLost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin.