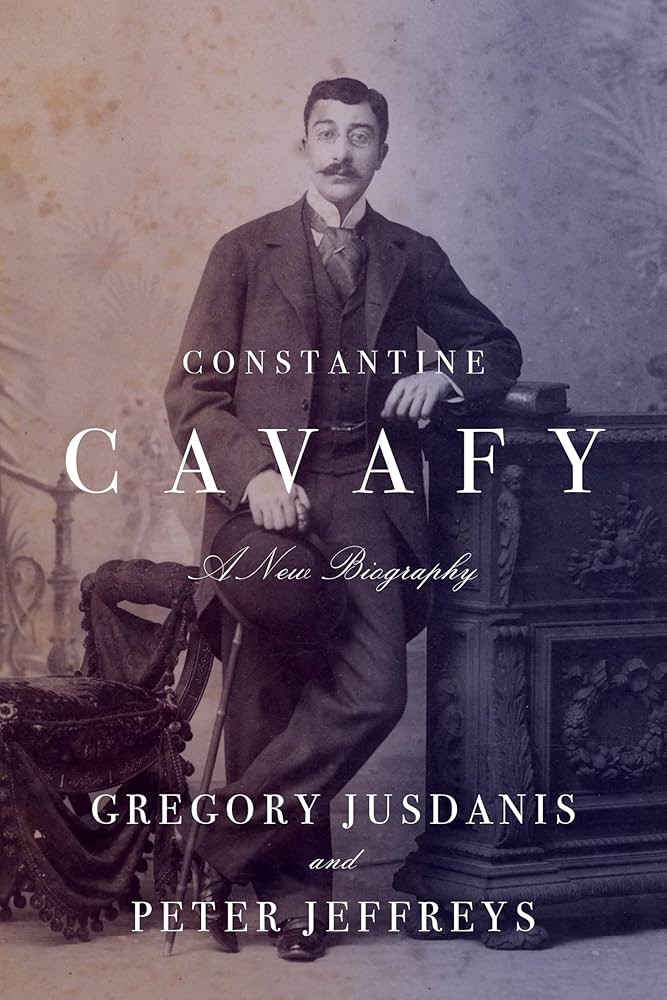

CONSTANTINE CAVAFY

CONSTANTINE CAVAFY

A New Biography

by Gregory Jusdanis & Peter Jeffreys

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

560 pages, $40.

GAY POET Constantine Cavafy (1863–1933) has been called the greatest Greek poet of the 20th century, a serious statement about a nation that produced Yiannis Ritsos and Nobel laureates Odysseus Elytis and George Seferis. Cavafy did not actually visit Greece until his late thirties, having been raised in Egypt, England, and Türkiye in a family of wealthy international businessmen. A friend said that he might as well be considered a Londoner, and he was in fact a British citizen.

Yet Cavafy was very much a part of the Greek cultural community, wrote largely in Greek (though fluent in English and French), and lived most of his life cocooned within the expatriate community in Alexandria, as Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys explain in detail in their new biography of the poet. He rarely emerged from this milieu and brought his young male partners to his apartment on Rue Lepsius, sometimes called “Rue Clapsius” owing to the presence of brothels near Cavafy’s home. His day job was respectable but obscure: a clerk and editor-translator in the local water bureau’s Third Circle of Irrigation, a delightfully Dantean name.

As his wealthy family’s fortunes declined to near penury after his father’s death, Cavafy’s poetic fame slowly increased, largely through constant self-promotion and a fortuitous meeting with E. M. Forster, who worked tirelessly to get English translations published for the reluctant poet, who was notorious for wanting to control every word and comma. When Cavafy died, he was the best-known Greek poet, remarkable because no book of his work was published until two years after his death. Instead, he handed out poems to admirers, often young men from the international literary community, to take with them to promote his work.

Cavafy’s brother Paul was also gay and a sometime poet, which may have been socially confusing until Constantine’s reputation rose and Paul descended into poverty. In addition, there is at least one instance of a fake Cavafy milking the name, which James Merrill noted in a 1975 book review. A credulous young tourist in Greece was visiting the bogus Cavafy, who apparently used the name to attract young men.

Cavafy’s attention outside his family’s connections was focused on the men he met in Alexandria. He liked the scruffier young hunks of the European parts of the city, but also young literary admirers. The latter often found themselves physically as well as professionally caressed while discussing poems with their affectionate host. Cavafy’s amorous tastes did not extend into the broader Egyptian population, though in his late teens and early twenties he probably explored the cosmopolitan bathhouses of Istanbul while living there with his mother. The authors note that in later life Cavafy was willing to pay local working-class youths for sex, while dyeing his hair and gently bemoaning his aging.

Some of these exploits made their way into Cavafy’s poems, as in “He Came To Read”: “He came to read. Two or three/ books lie open; historians and poets./ But after ten minutes of reading,/ he has given them up. He is half-asleep/ on the sofa. He’s completely devoted to books—/ but he’s twenty-three years old and truly handsome;/ and this very afternoon eros/ entered his perfect flesh, his lips./ The erotic passion passed/ into his flesh where all his beauty lies;/ without any foolish shame about what kind of pleasure.”

Cavafy did not write about sex acts in any detail—not a surprise in times and places where gay sex was illegal. In this, his approach was akin to that of James Merrill, Federico García Lorca, or Walt Whitman. Yet his appreciation of young male bodies was quite apparent, especially later in life when he was more willing to speak the name of his love. The authors spend considerable space on Cavafy’s poetics and how he developed his style, focusing on a significant change of approach that included more openness about the nature of male relationships in later poems.

In addition to this superbly researched volume, there is a significant literature about Cavafy and his work, including other books by its authors. The letters of Cavafy and Forster edited by Jeffreys may be of particular interest to gay readers, though Cavafy generally remains formal in these, while Forster chirps and flutters. The two met through a young friend when Forster was employed in Alexandria. This meeting led to Forster’s famous description of Cavafy: “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.” This period is also when 36-year-old Forster had his first sexual relationship, with seventeen-year-old tram conductor Mohammed el Adl.

Like Merrill, Cavafy did not write much about current events. His nationalism, to the extent that it existed, is often described as “Hellenic” rather than Greek, owing to his focus on ancient history. The authors note how Cavafy wrote about the doings of ancient peoples of the Levant, setting poems in their communities or writing as though he had been present. Born in the 19th century and famous in the 20th, he was poetically resident in the 6th century BCE, when his sexual tastes may have been more accepted. Even in the early 1930s he had no radio, phone, or even electricity, the installation of which he declined, preferring to remain mentally and physically in earlier eras.

In the poem “Hidden,” the closing lines by this somewhat melancholy poet speak to hope: “In the future—in a more perfect society—/ Someone made like me/ Will certainly appear and live more freely.” This poem, written in 1908, was not published until 1968, a year before Stonewall. Perfect societies remain to be seen, but today the poet’s Alexandria apartment is a museum to him, and his street is now Rue Cavafy, surely one of few streets in the Islamic world named for a gay man.

Alan Contreras, a frequent G&LR contributor, is a writer and higher education consultant who lives in Eugene, OR.