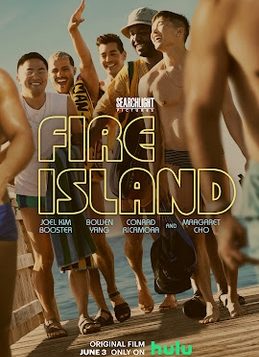

NO MAN IS AN ISLAND, as the English poet John Donne famously put it, and certainly not when he’s on Fire Island. None other than Oscar Wilde visited the gay-friendly vacation spot, specifically Cherry Grove, during his lecture tour of 1882. Roughly a century later, Andrew Holleran, author of Dancer from the Dance, grouped together the “revelries” taking place on Manhattan, Long Island, and Fire Island, but singled out the last as “nothing but a sandbar, as slim as a parenthesis,” the “very last fringe of soil on which a man might put up his house and leave behind him all—absolutely all—of that huge continent to the west.” Joel Kim Booster, the writer of Fire Island, is clearly not ready to leave this last fringe of soil behind. “It’s like a gay Disney World,” he tells us, “fun for the whole family”—except that his definition of family is not the traditional one.

Booster’s Fire Island is not only a light-hearted love letter to its eponymous locale but a randy reimagining of Pride and Prejudice. In the role of Noah (a corollary of Jane Austen’s feisty heroine, Elizabeth Bennet), Booster speaks directly to the audience and helps to translate terms that an “outsider” may not understand. For example, when a bitchy outsider describes his friend circle as “cute little friends,” Noah explains that this is code for “not a fuckable one in the bunch.” What Noah doesn’t decode is that the plot of Fire Island is based on Austen’s novel of 1813, though he told Matt Rogers and Bowen Yang, cohosts of the reigning gay podcast Las Culturistas, who are also his costars in Fire Island, that “we’ve got our gay Darcy!” The friend group at the heart of this entertaining comedy, perfectly timed for summer, mirrors the members of the Bennet family in Austen’s classic novel. Booster told the Late Show’s Stephen Colbert that, long after he watched BBC adaptations of Austen’s novel with his mom as a kid, he didn’t fully identify with Austen’s characters until he took a copy of Pride and Prejudice with him on a trip to Fire Island. “It wasn’t until I went to Fire Island for the first time that I actually brought the book with me to read for the first time, and I was so struck by how relevant it actually felt to my experience … navigating these weird class systems that gay men created for themselves.”

What does Booster mean by “weird class systems,” and how does he represent his journey as an openly gay Asian-American man? Booster was adopted and raised in a Southern Baptist household, which gave him a fiercely critical eye when it comes to the conventions, or “systems,” that rule social life. He has been an outspoken critic of the Grindr profile line “No fats, no fems, no Asians” as particularly toxic. In Fire Island, he puts a pair of Asian friends, Noah and Howie (played by Bowen Yang of Saturday Night Live fame), front and center. They lovingly bicker just as Elizabeth and her older sister Jane do, and in the opening scene Noah rightfully takes aim at Austen’s opener. “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in a want of a wife.” Those 23 words constitute the hastiest generalization in English literature, but it’s a sentence that Austen, with her characteristic irony, endeavors to undermine and ultimately undo as “universally” true. Spoiler alert: Mr. Darcy is one of the richest commoners in 19th-century England, but he has to work for Elizabeth’s affection and ultimately her hand in marriage, rather than simply accepting it as just another accoutrement of white male privilege. In the words of Noah, “That sounds like some hetero nonsense,” which he later criticizes as the golden rule of a “monogamy industry complex.”

Conrad Ricomora (in the role of Will) is the gay Darcy to Noah’s Elizabeth, and the name play is ingenious as readers of Pride and Prejudice learn, late in the novel, that Darcy’s Christian name is Fitzwilliam. “He’s from LA,” says Noah, “he’s super rich and thinks he is way better than all of us.” As the new “gay Darcy,” Ricomora plays Will convincingly as erudite and aloof, the perfect embodiment of what Austen described as Darcy’s “unsocial [and]taciturn disposition.”

It is often said that Austen was a prudish, even asexual, writer. True, in a work of juvenilia, her “History of England,” she makes a playful reference to the closeted King James I as a monarch of such “amiable disposition which inclines to Friendship” and to a “keener penetration [than]other people.” Aside from the frightful possibility that Lydia Bennet might “come upon the town”—become a prostitute—sexuality is otherwise nonexistent in Austen’s fiction.

Noah is well-versed not only in Austen but in such other literary heavyweights as short story writer Alice Monroe—his first meet-cute centers on a debate with Will over the best of Monroe’s works—and poet Walt Whitman. Rejecting the idea that he came to Fire Island solely to have sex, Noah insists that “I contain multitudes” to his four closest friends. These include Howie, the couple Luke (Matt Rogers) and Keegan (Tomas Motas) and the bookish Max (Torian Miller). The catty Luke and Keegan are meant to be versions of Elizabeth’s younger sisters, Kitty and Lydia. Of Max, Noah tells us in a snarky aside: “He claims he doesn’t come on this trip to hook up but he puts out in the meat rack just like the rest of us.” Margaret Cho plays Erin, the den mother and lesbian nurturer in what Noah describes lovingly as our “makeshift little family” and the “closest thing we have to a mother.” What Fire Island celebrates is the importance of a queer person’s “chosen family,” the group of friends and lovers selected for companionship and emotional support. Howie is like a brother to Noah and, sharing a joint on the roof of Erin’s bungalow, confides: “I like the rom-com stuff, like kissing in the rain, standing outside my window with a boombox, or kissing in a gazebo.”

Fire Island is not the first gay film to reimagine Austen’s most popular romance. Before the Fall (2016) was there first, even if it was a little on-the-nose with a pair of lovers named Ben Bennet and Lee Darcy. In a subtler way than Before the Fall, Fire Island borrows Austen’s marriage plot, which she herself borrowed from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing—think of the verbal sparring that functions as another form of foreplay between Beatrice and Benedict—and unites Noah and Will as what Austen calls “the happiest couple in the world.” True to the original, Fire Island delivers a happily-ever-after finale—a heart-to-heart between Noah and Will while sitting on the dock of the bay, a shimmering sunset, even Donna Summer’s “Last Dance”—and the assurance that true and lasting love is always within reach.

Colin Carman, author of The Radical Ecology of the Shelleys and a former fellow of the International Jane Austen Society, teaches British literature at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction, CO.