Warhol & Mapplethorpe: Guise & Dolls

Wadsworth Atheneum

Museum of Art, Hartford, CT

October 17, 2015–January 24, 2016

Warhol & Mapplethorpe: Guise & Dolls

Edited by Patricia Hickson

Yale University Press. 184 pages, $60.

THE FIRST exhibition ever to consider Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe together—their careers overlapped from the late 1960s to the late ’80s—this show is filled with both lovely surprises and a few letdowns. The star of the show is Warhol’s Ladies and Gentlemen, silkscreen paintings commissioned by Italian art dealer Luciano Anselmo of African-American and Hispanic drag queens, habitués of the Gilded Grape, a Hell’s Kitchen bar.

Mapplethorpe had been aware of Warhol’s work as far back as 1964, when the former was nineteen and young enough to be Warhol’s son. (The exhibit catalog’s detailed timeline puts both artists’ lives in context with one another.) Bob Colacello, a close friend of Warhol, recalled in Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (1990) that he printed some of Mapplethorpe’s work in Interview magazine, of which he was editor, and Colacello and Mapplethorpe became friends. “Andy disliked Robert,” Colacello recalled, and Robert “was afraid Andy would steal his art ideas.” On the other hand, “some would say [that]Robert’s early mix of photography and painting derived directly from Andy.” Patricia Morrisroe states in Mapplethorpe (1995) that his attitude changed from “adulation to competitiveness,” from a desire to be mentored to a desire for friendship, but ultimately he was disappointed by Warhol’s “vacuous personality.”

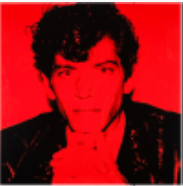

This exhibit includes several images by the two artists of each other, the most compelling of which, both from 1986, are used to illustrate the front and back covers of the exhibit catalog: Warhol’s red silkscreen of Mapplethorpe with his chin resting contemplatively on his fingers, Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Warhol surrounded by a halo of light, possibly an allusion to Warhol’s frequent use of Byzantine iconography. Morrisroe describes Warhol looking “part saint, part ‘Wizard of Oz.’”

Mapplethorpe—whose lover and mentor Sam Wagstaff was curator of painting, prints, and drawings at the Wadsworth Atheneum in the early 1960s—is represented by, among others, images of two of his androgynous muses, musician Patti Smith and bodybuilder Lisa Lyons; brief videos accompany those photographs. There are a few of the S&M images that created such a fuss in 1989 when it came light that the National Endowment for the Arts had partially funded the traveling exhibition—so frequently seen that they’ve lost much of their power to shock. Less frequently seen are beautiful images of the drag queen Aira, made up to represent a 1930s Hollywood screen star.

It is unfortunate that the Wadsworth Atheneum decided not to provide headphones or seating for the three hour-long videos, episodes of the “Factory Diary” series, of which the most coherent is a presentation of the artistic process involved in silkscreening a drag queen. That said, the museum should be lauded for doing something that hasn’t been tried before involving two formidable artists of the last century.