FOR MANY YEARS, I taught Irish literature in Chicago, and I would always tell my students: the Irish love to debate, and argue about anything that’s not personal. We like to pontificate with the best of them but when it comes to personal matters, we become awkward, uncomfortable, and unusually quiet. So, when it comes to approaching intimate subjects, decorum is required. You do not rush in where angels fear to tread. Instead, you avoid the subject.

For instance, my coming out was not accompanied by a fanfare. There was no great catharsis to be followed up by a rainbow party. I was forty years old and quite happy inside the musty old closet of my own making. When it came to coming out, I simply moved from Ireland and took up residence with my partner Larry in Chicago. Everyone knew, but no one really said anything about the new situation. My father, a very pious Catholic, never suspected that one of his five sons might be gay. The closest we came to having a discussion on the subject happened quite accidentally. We were driving downtown, when all of a sudden, he pointed at a man walking down the street and said, “See him? He’s a wee bit gay.” When I later told this story to my partner, he said: “You should have asked him, which bit of the man was gay?”

In retrospect, this moment might have been the perfect opportunity for disclosure, but I’m Irish and we don’t do that sort of thing. It’s too personal. My father died none the wiser about my sexual orientation. But when it came to my mother, that’s a different story. She and I never discussed the subject, even though she had stayed at our Chicago home several times. She knew, and I knew she knew, and she knew that I knew she knew. It was an open secret after all.

There’s no doubt in my mind that the matter of my sexuality was scrutinized, dissected, and interrogated by the other family members, but never directly with me. Having my domestic setup an open secret among the family worked for me. It meant that there were no embarrassing questions to answer and no awkward silences to quickly fill with mindless trivia. I could navigate my visits back home without fear of confrontation. At least, I thought I could, until one of the last trips back before my mother also passed away.

We were driving home from the casino. She loved a little flutter and, in Irish terms, our spell at the casino was quality family time. Joined by a common hope of winning, we bonded over the one-armed bandits. On the way back, from a not so lucky afternoon, we ran into traffic and were slowed to a crawl. Music played on the radio, and we laughed about our misfortune. All seemed good until traffic slowed to a halt. As if on cue, the conversation dropped to a more serious tone.

As soon as mother started with “I just want you to be happy,” my heart started racing. I’ve never had an anxiety attack, and I’m not claustrophobic, but in those moments the car wasn’t big enough for both of us, and my nerves were shot. I was convinced that the prelude to mother’s opening comments was inspired by Jerry Springer. For a conservative Irish Catholic, mother enjoyed the freakish absurdities that Springer managed to find. I suppose I should be grateful to Jerry since against the backdrop of these offbeat characters my being gay must have seemed normal to her.

I desperately tried not to fixate on what she was saying. Watching the traffic lights in the distance, I prayed for a distraction, but none came. I’m convinced God was up there laughing his ass off at my increasing discomfort. Her speech hit a crescendo when she confessed to be disappointed at not having grandchildren from me. It was at that point I wanted to laugh out loud. She already had twenty-plus grandkids as it was. One more from me would not have made her life any easier or fuller.

“I thought you’d get married and settled down with children.” I tried to make light of the conversation. “You should be grateful that never happened. There’s enough Boyles around to re-populate the world, should they be called upon to do so.”

My diversion tactic came to naught. Mother could not be dissuaded from her mission. This was the conversation she had wanted to have for years, and I could not stop her. And given that I couldn’t very well push her out of the car, I was forced to accept my fate. As I sat there in my discomfort, I began to understand what an important step this talk was for her. Since it was foreign to our culture to say the things she was attempting to put into words, it was quite a brave thing for her to do.

I can never remember my parents ever being very demonstrative. If they were proud of you or thought well of you, you heard it from a third party. When I graduated with my doctorate, I could tell they were pleased, even if they didn’t fully appreciate the achievement. I didn’t need them to say anything. They came to the ceremony and that was that. Academic accolades are one thing, but they are not personal. Mother was attempting to unlearn her own cultural conditioning, and all I could do was squirm in my seat.

In what seemed like an eternity, but was most likely only ten minutes, she had surpassed me in her ability to evolve beyond our Irish limitations. I was the one more traveled. I was the smart one. But she was the one more open to change. In those minutes, I knew that it is never enough to live with an open secret.

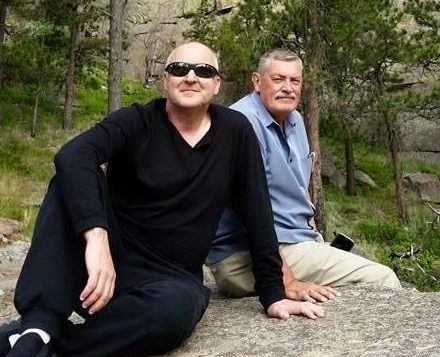

Terry Boyle, originally from Northern Ireland, is a playwright, poet, and former professor of literature who lives in the Palm Springs area with his husband Larry and their two dogs.