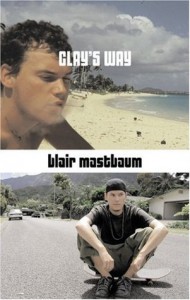

Clay’s Way

Clay’s Way

by Blair Mastbaum

Alyson Books. 242 pages, $12.95

BLAIR MASTBAUM’S impressive comic debut novel, set in Hawaii, presents the serious love choices of its fifteen-turning-sixteen-year-old narrator Sam, an unskilled skateboarder who has a crush on the slightly older Clay, an accomplished surfer. Rebel Sam listens to music “with lyrics about not fitting in and hating the status quo.” Clay likes anarchic punk rock but aspires to the unexamined life of “cool brahs, hot chicks, good waves.” The novel traces Sam from the alienation and anomie he shares with his friends—who drink, take drugs, and party all night—to a transforming awakening achieved through an examination of his desire for love and intimacy with Clay.

When the macho Clay seduces the eager Sam and professes “I love you, man” but doesn’t follow through emotionally, Sam must confront his reasons for choosing Clay as a love object. Do we fall in love with our opposite, the person we want to be? Sam confesses that surfers like Clay have “egos that I hate, but at the same time they turn me on.” The physical charge that Clay gives Sam is not enough, causing Sam to ask, “Why can’t [Clay] be a genius at expressing himself, making me feel loved and cared about?” Sam’s young woman friend Kendra tells him she knows he’s gay and provides Sam with a clue to the surface of Clay’s masculinity, saying that his macho surfer attitudes—his ego—could have been developed to hide the fact that he might be gay himself.

The drama with Clay inspires Sam to write his eccentric version of haiku poetry, which, like his skateboarding skill, turns out to be more enthusiastic than accomplished. Midway through the novel he asserts art’s pre-eminence and his own solace: “I’m an emotional haiku poet. I have the right to cry over the boy I love.” Sam records his first rapture in one poem (italicized in original):“Clay’s bed, summer, afternoon sweat is love, riding home smiling.” The emotion changes when Clay doesn’t match Sam’s love: “Lonely boy tears, mixing with raindrops, can’t tell the difference.”

Sam expresses his physical relationships with exhilaratingly adolescent perceptions. He appreciates his own body and its smells, and when Clay and Sam argue, he notes: “His anger smells like a rancid variation of how he smells during sex.” Sam’s later desire for the hippie Anar hits him unexpectedly: “I want to strip him naked and rub my face all over his body, smelling him from his knees to his dick to his head.”

Sam reveals his writer’s æsthetic in terms of Clay’s body, which is “skinny but with muscles like the perfect amount—not from working out, but from surfing. They’re real muscles, not decoration.” That æsthetic describes the style of Mastbaum’s touching novel. Lean prose moves the story swiftly to display powerful but not overblown emotion. Sam’s bald statement that “the world is not worth being in without Clay” is heartbreaking. His simple description of “the healthy scent of oncoming rain” evokes a Hawaiian nature that’s more elemental and sustaining than are overwrought descriptions found in travel writing.

Clay’s sexual identity remains ambiguous, but the affair gives Sam “something to be miserable about, and writers need that.” The book ends before Sam becomes a fully realized artist, one who might even write a novel. Twenty-five-year-old novelist Mastbaum’s quirky narrator and comic verve propel the reader through this story of painful yet instructive young love made art for readers of all ages.

_____________________________________________________

Dan Luckenbill, who works at the UCLA Library, is a writer and archivist based in Los Angeles.