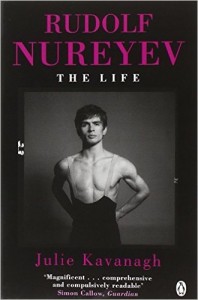

Rudolf Nureyev: The Life

Rudolf Nureyev: The Life

by Julie Kavanagh

Pantheon, 782 pages $37.50

IN APRIL 1962, Rudolf Nureyev was convicted under Soviet article N43 of treason against the state. Traitor number 50,888 was not present to defend himself against the charges, which had resulted from his dramatic defection to the West at Le Bourget airport, Paris, the year before. The judge took evidence of Nureyev’s previous good record into account, and he was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment, rather than to execution. Nureyev’s Russian friends were relieved. Some thought he might even return.

At the time, Nureyev was in London, with no such thoughts, putting the finishing touches on his own autobiography, which was published in English later that year. It contained, inevitably, his own account of the airport drama, which was clearly—we now know—embellished in numerous particulars. There was also a necessarily sanitized sketch of his upbringing in Ufa, a large Soviet city in the predominantly Islamic region of Bashkir, but by any account the middle of nowhere, his desperate struggles throughout his youth to realize his dream and become a dancer, and then his studies with the Kirov in Leningrad (St. Petersburg). Nureyev had to use sleight of hand with many particulars, of course, to protect the friends and acquaintances he had left behind, most of whom he would never see again.

The dancer would later regret the element of hubris in recording his life at the age of 24. (He also managed to get many details wrong in the bestseller—including, astonishingly, the date of his defection.) At the time, however, he must have been advised that it was the best thing to do. The memoir would have seemed like a fast way to deal with the constant importuning by the media. The sensational story of his defection had been one of the Cold War’s most vivid tableaux; it coincided with news of the astonishing performances in Paris that announced his dancing supremacy.

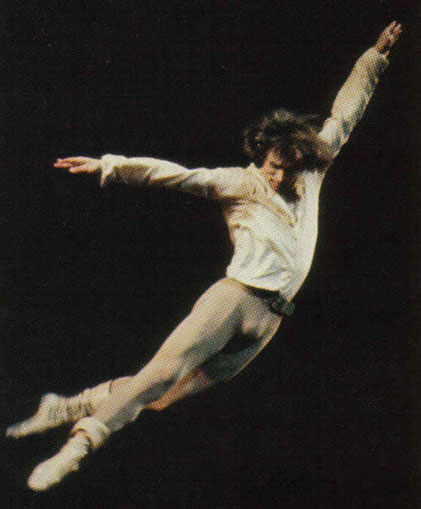

Nureyev had became a global sensation so fast that the media simply couldn’t keep up with him—like some of his dance partners, indeed, one of whom Nureyev famously allowed to crash to the ground. “She has to help me and she didn’t,” he retorted. “I’m not going to drag her up.” Behind this incident lies the fact that—with the sole possible exception of the competitive partnership with the much older Margot Fonteyn at the Royal Ballet in London—Nureyev revolutionized ballet by putting the male performance—namely, his own—first.

This revolutionary move followed decades in which balletic art had become concentrated on the opportunities afforded to the ballerina. Vaslav Nijinsky, the only male performer in the history of ballet with a claim to rival Nureyev’s legend, had, it is true, first developed—and feminized—the potential for men in performance. However, the early truncation of Nijinsky’s career had combined with the failure and/or unwillingness of later choreographers to build on these initiatives. Nureyev may have itched to work with George Balanchine—but Balanchine had said: “Ballet is woman.” He thus had to begin the transformation of ballet into a male-focused art virtually from scratch. Technology here plays a critical role in the foundation of a legend, or legacy. History has left us nothing of the performances that made Nijinsky famous, but we have almost everything that built Nureyev’s career. (Not only was Nijinsky not filmed; the notation of choreography was so rudimentary in his day that much of his style remains a matter of informed conjecture.)

Just as Nureyev grew to appeal directly to his mass audiences, and to ignore the cavils of critics, so too he saw the memoir as a method of bypassing the media. He’d earn well from it also. This money he truly needed in 1962. On defecting, although famous, he became, suddenly, unemployed, and to some degree unemployable, as established companies in the West could not embrace the fugitive without losing their close and lucrative relationships with both the Kirov and the Bolshoi. Nureyev’s first position as a dancer—with Georges de Cuevas’s company—was an obvious comedown; his peers onstage were competent—barely—and the productions were constructed on a shoestring.

He had, then, little time and less patience with journalists. One cheers to learn of his behavior, having been corralled into being interviewed by Andy Warhol, when he was asked “What color are your eyes?” and he replied, “The interview is canceled.” There were, however, two conspicuous exceptions: Nigel and Maude Gosling, who together wrote on dance for the London Observer newspaper under the byline of “Alexander Bland.” His own English was still poor, so Nureyev must have been helped considerably with idiomatic speech by the Goslings, who soon became his adopted London “family.” “Bland” is credited as editor of the memoir and provided an introduction.

Nureyev’s memoir has been superseded by a number of biographies since his death in 1993. However, Julie Kavanagh’s Rudolf Nureyev: The Life—the fruit of over a decade of research—should probably be the final word on the subject, correcting many misconceptions of earlier books. (It won’t be, of course.) Kavanagh’s book is not for the casual fan, however: it runs to about ten times the length of Nureyev’s autobiography. Given this enormous detail, the narrative flow isn’t always transparent. John Carey, however, a professor of English at Oxford, reviewing the work, has written an extraordinary denunciation —not just of Kavanagh’s book but of the very idea of taking ballet seriously at all:

Describing ballet in words comes down, essentially, to long, precise accounts of where people put their arms and legs, and this has severe limitations as reading matter. Further, ballet is mindless compared to other arts—as mindless as, say, football—and this restricts what can be written about it. Despite its fusillade of detail and its grand narrative sweep, Kavanagh’s book does not contain, in all its 800 pages, a single idea—not, that is, a single new or interesting thought about the physical or metaphysical universe. It is impossible to imagine the biography of a novelist or a painter or a scientist about which this could be said. But with ballet it is difficult to avoid, and the consequence is, intellectually, a howling wilderness, swept by gales of trivia, scandal and society gossip.

It is a terribly wrong-headed and philistine response, but Carey has more to say. Nureyev as a subject is intrinsically unworthy because he was “shamelessly exploitative, using people as stepping stones and then discarding them.” There’s clear disapproval of Nureyev’s sexuality, though Carey couches this in terms of his impatience and infidelity, rather than his being attracted to men: “Several of his short-term partners found that all he wanted was ‘mechanical’ sex, without personal involvement. ‘I told him he should hire a robot,’ one protested. Increasingly he gravitated towards anonymous encounters in public lavatories, New York bathhouses and other gay cruising venues.” At this point, I suspect Nureyev emerges as a fascinating figure for many readers. The idea that biographies thrive on the goodness of their subjects, moreover, is of course laughable.

In the memoir, Nureyev—who immersed himself in all of the arts throughout his life—named his three favorite artists as Dostoyevsky, Scriabin, and Van Gogh (citing the “generosity and violence” he found in all three). Not bad for a 24-year-old who had scarcely had a formal education at all. He may often have been associated with pop cultural movements of the 60’s because of his leather cap, his Bohemian clothing, and that signature haircut. Nureyev was, however, distrustful of anything he suspected of gimmickry, and he embodied a widely-displayed Russian tendency to praise only High Art. Nevertheless, Otis Stuart—more of whom shortly—makes a meal of Nureyev lunching with Mick Jagger and immediately speculates upon a sexual link: “Can we talk four fabulous lips in one bed?” Kavanagh corrects this impression, noting that Nureyev found the singer “dead boring” and that the encounter was a dead end. It’s possible that the Rolling Stone remained fixated. (There’s a stunning contradiction throughout a chapter that Stuart entitles “The Great Gay Myth: ‘I Slept with Nureyev.’” He decides, finally, that such stories mostly aren’t mythical after all: “If the number of conquests is perhaps inflated, it is not, one suspects, by much.”)

Nureyev listened to nothing but classical music, and when he could no longer dance, he began a career as a conductor. Here again Carey’s cultural arrogance and snobbery come out. He seemingly can’t stand the idea of an upstart from nowhere improving himself—or doing so very much on his own, extramural terms. Nureyev’s relative reticence on the literature he devoured, for example, has the professor crying foul:

How much he actually read remains uncertain, though, and she [Kavanagh] records nothing of account that he said about books. He sought reflections of himself in literature, and was convinced, for example, that he and Byron were soul mates, despite the fact that he was barely articulate and could not finish Childe Harold. Towards the end of his life, he became intrigued by the idea that he might be a descendant of Milton’s Satan. This was wildly self-aggrandizing, of course, and Milton’s arch-fiend would have been outraged to find himself associated with the peccadilloes of a mere ballet dancer. All the same, in its recognition of Satan’s and his own essential egotism, it shows a more accurate perception than any other of his literary comments.

A “mere ballet dancer”? One can imagine Nureyev’s cursory contempt for Carey’s term-paper jibes. Nureyev wasn’t a student of literature, in any case, but a dancer, whose mastery of technique and record-breaking career longevity required constant training along with all the unendurable demands of the craft. Asking him to exhibit an appropriate intellectual engagement with books on all occasions is like expecting a tutor of literature to ride in and win the rodeo.

KAVANAGH HAS BENEFITED hugely from the political changes in Russia, which have enabled many more of those who knew the dancer to speak since his death. (It helps that so many dancers have unusually long lifespans; when Nureyev took to the Kirov stage again in 1989, he was applauded by the hundred-year-old Anna Udeltsova, his first tutor in Ufa.) A trained dancer herself, Kavanagh brings empathy to her account of Nureyev’s often appallingly childish behavior. She neither excuses nor judges, but reminds us of the pressures of a career like his, at the top of his game and after. There are longeurs, and occasional failures of emphasis, but this book gets closest to explaining a Tatar genius who was—as Winston Churchill famously said of Russia—“a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

Some of the more difficult terrain Kavanagh covers relates to the question of Nureyev’s sexuality. During their partnership, he and Fonteyn struck many, including intimates, as an item. Kavanagh tends to discredit the idea, though Nureyev certainly made love to women on occasion, probably including Xenia, wife of his favorite dance tutor at the Kirov, Alexander Pushkin. (Nureyev acclaimed her later as “great in bed,” but also noted that she “looked more like a boxer than a dancer.”) Equally certain is that he had a strong preference for men sexually. The discretion vital to homosexuals in Stalinist and post-Stalinist Russia means we can know nothing about Nureyev’s erotic awakening there—if it happened at all. His peers have always argued—even now, when discretion isn’t needed—that before his defection Nureyev had no sexual character at all; he only danced.

It’s remarkable to discover, then, the litany of innuendo and presumption that characterizes the worst book on the dancer, Otis Stuart’s Perpetual Motion, which belongs to that subgenre of celebrity biography, the “documentary of excess.” Published right after Nureyev’s AIDS-related demise, this biography was blatantly conceived to capitalize on the notoriety of this cause of death. AIDS talismanically reflects the usual supposed characteristics which make its onset “inevitable”: an addiction to risk, a prevalent fatalism, discontent with one’s homosexuality, sexual passivity, and rampant exhibitionism.

Kavanagh, meanwhile, more dryly observes how Nureyev’s fame across the West coincided with gay men’s sexual liberation, and notes where possible (rarely) what her subject seems to have been up to. It was hardly unusual—notwithstanding such burgeoning opportunities—for gay men to indulge rather secretively, after all, and though Nureyev was about as “out” for the age as it was possible to be, he wanted his movements untraced for understandable other reasons (the KGB). Stuart, however, provides an apparently personal account of watching the dancer climb the stairs at a notorious Parisian gay bar, the Trap. He gave himself to the throng of incredulous patrons who followed him into the back room, Stuart states—though presumably he didn’t follow? Perhaps he could hear what he couldn’t see. This was in the early 1980’s, “when sex was still a verb,” as Stuart oddly puts it. In glancing at this story, Kavanagh makes her only reference to Perpetual Motion—though if she doubts her source, she does not state so.

If Kavanagh shies away from documenting, or ruminating over, Nureyev’s precise sexual tastes, Stuart does so fearlessly: “There are two schools of thought on what position Nureyev preferred in the act. The first is that Nureyev, as a veteran of the era remembers, was interested simply in planting the seed, rather than receiving it; the second, the exact opposite, that Nureyev was, in the words of the writer Joel Rodham, ‘a notorious masochist.’” The two theses are presented as incompatible—though of course many gay men, then as now, have enjoyed experiencing a variety of sexual roles and alternating between them. Nureyev virtually conceded the point in one untypical aside: “’I know what it is to make love as a man and a woman.” Epidemiologists have argued that this fact facilitated the very rapid spread of HIV and AIDS. A range of opportunistic infections struck Nureyev from the late 70’s on, including one vicious attack of pneumonia, suggesting that he contracted the virus early on. At least one later partner, Robert Tracy, died of the syndrome and privately argued that the dancer had infected him: “You know that it is possible considering the kind of sex we had.”

In fact, Stuart repeatedly figures Nureyev’s sexuality in terms of a hungry passivity, and even interprets Nureyev’s power on stage in terms of the allure of his ass. An unnamed “veteran” fellow performer concedes that Nureyev liked to upstage his peers: “There was this thing Rudolf used to do, regularly, when he wasn’t actually dancing but thought the dancing that was being done was less than interesting. He’d walk upstage, turn his back to the audience, and flex his butt. It worked every time.” Perhaps. In terms of his performance, one theory certainly would be that Nureyev accentuated its feminine aspects in response to the ever-growing legions of female fans—not so much to put them off, nor even to beguile male spectators. Probably it wasn’t conscious at all. Carolyn Souter recalls, though, how Nureyev lamented that it was “always the women, never the men” giving roses at the stage door.

But if we’re going to be profane about the sensory attractions of ballet, it’s nevertheless just as true that many spectators were fixated by another attribute of Nureyev’s. This one was frontal. He was famously proud of his cock size, and the tight costumes he insisted on wearing did everything to accentuate it. Nureyev routinely invited stagehands and others—usually women—into his dressing room while naked, staring them down. Souter’s memoir has a vivid account of just such a moment. She opens the door to be confronted by Nureyev “standing black-lit,” “his arms … stretched out, questioning me.” At 42, the dancer nonetheless reminds Souter of Michelangelo’s David in his physical perfection. Like David, perhaps, Nureyev embodies a potency enshrined in—or notwithstanding—a paradoxical inferiority. For Souter notes that she is taller than he. Yet everything coheres to offer a vision of power, size, and strength:

It is impossible not to look at all of him, to take him all in and I know that this is exactly what I am meant to do. He is slightly shorter than me. His skin is pale, almost luminous. It is the most beautiful body that I have ever seen. He is broad chested, every muscle defined, carved, worked, tuned, with a slim waist. His arms are muscular, elegant and end in sinewy shoulders. The fact that he is male is not in question. There can be no doubt. He has huge thighs in comparison to his slim waist, and large calves that end in knotted, dry-skinned, wide, peasant-like feet. His big toes curl inward to rest on the other toes. There is not one inch of him that is not built for purpose, for work and for looking at.

Nureyev had entirely constructed himself. He had been “feeble” in gym class at school, according to one classmate. In this process of self-construction, he built what he needed to dance, certainly, but the result was an almost impossible human form (as photographer Richard Avedon immediately understood, getting Nureyev drunk at the first of many photo sessions and persuading him to pose nude). In this, he resembled no one so closely as Arnold Schwarzenegger, whose own unlikely body Nureyev conspicuously admired when they met. “How do you taste?” he asked, biting Arnie’s finger. (As a teenager, Nureyev had swung from the ropes of the new Ufa Opera House, imitating that earlier Eastern European-turned-American, bodybuilder and actor Johnny Weissmuller, whose Tarzan films he’d seen).

He liked teasing both ladies and men. Naturally, in Souter’s case—and presumably Schwarzenegger’s—Nureyev wasn’t making any sort of pass. He was not so much fearful of women as utterly dismissive of them—and not only sexually: “I am probably a male chauvinist pig but I consider men to have a better organized brain and better able to separate themselves from nature and their own nature. Men respond to music better. They are the leaders in all the visual arts and in architecture. Men are better at the military; men are better cooks; men are better at everything. They also have the highest level of sensibility and sensitivity.” Perhaps he spoke the truth, then, when he told one reporter that his favorite dance partner had been Miss Piggy on The Muppet Show!

Nureyev’s mythical status today owes much to his success at popularizing ballet—and not just on television. Millions may only ever have seen him perform with Miss Piggy in Swine Lake. But they learned his name. If Nureyev became ballet’s first “pop icon,” as Kavanagh has it, it was really because he and Margot Fonteyn had together become a sort of global brand. With Martha Graham and Fonteyn, Nureyev even posed for a lucrative advertisement for fur coats.

Stuart makes no reference to Nureyev’s legendary endowment, which even Miss Piggy in prime time had managed to clock, since his preferred topic is his subject’s supposed anal insatiability. One reported exchange reads: “Don’t you ever get enough sex?” “No.” Even a reference to the “form-fitted boxing shorts” the dancer wore for his lamentable performance as Valentino in Ken Russell’s movie only leads Stuart to point out “a steamy sense of S&M,” not the conspicuous bulge others worried over. In Stuart’s version, Nureyev sought out dominant tops for dangerous sexual acts—essentially because he lacked self-worth. Lingering over the “darker corners” of his subject’s erotic repertoire, Stuart mentions Monique van Vooren, a glamorous actress renowned for her younger lovers. Van Vooren retaliated when Nureyev stole her current beau by penning a trashy roman à clef about him, Night Sanctuary. (Astonishingly, the second, worthier novel based on Nureyev’s life—Colum McCann’s Dancer—manages to make him dull.)

Van Vooren argued to Stuart that “Rudolf was tortured, tormented by his sexuality. He was ashamed of being homosexual. And I think he wanted to be degraded. He liked street boys, toughs, the lowest of the low.” The painter Michael Wishart underlines the point in Diane Solway’s earlier life: the dancer preferred “rough-trade pickups, sailors, lorry drivers and the like” for instant gratification. Van Vooren has an interesting thesis, but it may not be correct. Just as pertinent to Nureyev’s alleged penchant for partners of low social status was his identification with them, not in opposition to them. Nureyev’s every ascent, every incursion into the realms of art, culture, film, sophistication, fame, glamour, money, influence and reputation reminded him that he did not, by rights, deserve it. He was an interloper who brandished the fact: “Always I intrude and always I am made to feel this.” Back at school, his Tatar peers mocked his rare blond features, nicknaming Nureyev “Adolf” after the hated enemy of Russia. It is intriguing that a man who could roundly dismiss women’s contributions to the arts, and their potential in them, excelled in that very discipline in which they had become dominant, albeit by virtue of the choreographing instincts of men, pre-eminently if not exclusively.

Equally compelling is this comment by Nureyev, in which, rather than identifying with the easy certainties of masculine achievements, he argues that any dancer perforce enters into an abusive power dynamic with his or her audience: “Like all performers, I am masochist. Audience is sadist and vice versa. The moment they see blood, see weakness, they will tear you to pieces.” When facing a host of serious health complications relating to his HIV-positive status, Nureyev reacted with characteristic defiance, and phallocentric rhetoric: “I am Tatar. AIDS is not going to fuck me, I’m going to fuck AIDS.”

This belligerence, however, was only one aspect of his conception of the Tatar character—at least as he had framed it in his autobiography in 1962. In the following passage, he not only pinpoints what made his performances so unforgettable and distinctive—the succession of incompatible, often apparently technically impossible masculine and feminine balletic effects—but also suggests that this ability was born of a sort of war within his own temperament, one which related to the instability or unattractiveness of being, or being seen as, one “thing”:

I can’t define exactly what it means to me to be a Tatar and not a Russian but I can sense the difference in my flesh. Our Tatar blood runs faster somehow, is always ready to boil. And yet it seems to me we are more languid than the Russians, more sensuous; we have a certain Asiatic softness in us, yet also the fougue of our ancestors, those lean superb cavaliers. We are a curious mixture of tenderness and brutality. … Tatars are quick to catch fire, quick to get into a fight, unassuming yet at the same time passionate and sometimes cunning as a fox. The Tatar is in fact a pretty complex animal: and that’s what I am.

Nureyev acknowledges here what a school report stated, when he was eleven: that he was “sometimes rude to his friends because he gets mad easily.” The report, however, did not suggest this made him typically “Tatar”; rather, it was a point of special concern. Still, if “Tatar” meant ruthless and aggressive to many, that is what Rudolf later resembled. Everyone ended up using bestial comparisons to describe him as a man and as a performer. Noël Coward found him “a curious wild animal, very beguiling and fairly unpredictable,” pretty much Nureyev’s self-estimate in the quotation above.

Animalistic he must have been. But did he—out of temper over a foiled would-be sexual conquest—shit on the steps of Franco Zeffirelli’s villa? The evidence suggests so, but it’s inconclusive. Shit came to form an interesting part of his vocabulary. “You shit-fuckers, shut up!” he shouted at a hand-clapping audience in Chicago, frustrated by his characteristic lateness. In 1976, he was dismissed as too “earthy” for Glen Tetley’s new piece, Pierrot Lunaire. But Nureyev hounded Tetley: “I’ll do anything you want me to do. I will shove my hand up my ass and pull my shit out and rub it in my hair.” On his final British tour, he warned one unfavored critic who planned to attend a show: “I will get a bucket of shit and throw it on her head.”

BALLERINA Violette Verdy found Nureyev “like a modern Genghis Khan.” Then again, the composer Vladimir Dukelsky had recalled the assertively homosexual founder and chief of the Ballets Russes, Serge Diaghilev, in precisely the same terms. Like Diaghilev, Nureyev argued for costumes and props that were impossibly extravagant, unrealistic, and costly. When he came to run a ballet company in Paris, his belligerence and Diaghilev-like favoritism swiftly alienated everyone in the company. But the real comparison backward in time has to be with Vaslav Nijinsky, whose example—and tragic late years—preyed on Nureyev’s mind. It has been argued that Nijinsky fell in with Diaghilev romantically because of a father-figure complex. An intriguing story concerns Nureyev’s relationship with Hamet, his father—albeit one recalled by a third party he had told. Aged ten, “Rudik” joined his dad for their weekly visit to the public steam bath in Ufa (they lived in one room with no toilet facilities), only to spring a sudden erection. Hamet beat his only son hard.

Hamet was a soldier and card-carrying Communist—entirely unlike Rudolf, who suffered much for his refusal to tickle the euphemistic clitoris of the Party, and not only during his Russian years. In Paris, after his defection, he performed while being pelted with fruit by enraged French Communists. After leaving the USSR, he never saw his father again. But it was his mother Farida whom he missed, often acutely. Consequently, I suspect, he made the mistake of seeking ways for his other female kin to join him in the West. His sister Rosa got out anyway by marriage, bringing her nightmarish daughter Gouzel with her. Rosa’s attempts to mother Rudolf, however, angered the dancer and drove him away from her and her Bashkirian cooking. Soon after they arrived, Rudolf was wailing: “What have we done? Send them back!” Nureyev did return to Ufa once, as both Farida and the Soviet empire stumbled towards their respective ends. It provides a moment of neat narrative closure for biographical storyboarding, but it must have been truly awful for him. Farida scarcely recognized him, did not speak, and died months later. Nureyev understandably blamed the Soviet system for keeping them apart.

I kept thinking over Nureyev’s strong identification with Nijinsky, the Russified Pole whose complexities dissolved into schizophrenia. (One of the great Nureyev “what ifs” concerns a projected biopic about Nijinsky, to be directed by Tony Richardson with a screenplay by Edward Albee). Nijinsky, notoriously, had “betrayed” Diaghilev, his sometime lover, by impulsively marrying Romola Pulszky, a Hungarian countess who had ardently pursued him. Nijinsky had not been sexually satisfied by the effete Diaghilev, whose determination and control predominated only in public; his handshake was the limpest you could find. Still, Nureyev said that the “abnormal” Diaghilev-Nijinsky relationship “produced very interesting things. Then there is the normal relationship, which produced zero. So, what is normalcy?”

The closest connection between the two dancers, strangely enough, may not reside in their sexual temperament but in their magpie-like pursuit of lucre. Nijinsky saw his own opportunity in Romola’s capacity to bankroll his envisaged career. Nureyev—like Dalí, Warhol, and too many others—came to see his own career, regrettably, largely in terms of box office returns, not creativity. Almost none of these earnings ever got near to the taxman: Nureyev wasn’t kidding about his “cunning” in financial affairs. His estate was finally valued at $30 million; he certainly died the wealthiest dancer in history.

The years after Nureyev’s AIDS diagnosis coincided with the inevitable decline of his dancing abilities. But money drove him on. No biographer can shrug off the sense of diminishing achievements over the last decade. Of course, ballet’s cruel treatment of its aging practitioners is notorious, and it isn’t personal. But in Nureyev’s case, worry and fear about his health accompanied the usual sense of loss. He had a superstitious and infelicitous attitude toward medical expertise. He secured the services of one of the most knowledgeable French specialists in hiv/aids, Dr. Michel Canesi. He could afford to employ Canesi exclusively, almost as he had done his masseur earlier in his career, and for a time this is exactly what happened. Remarkably, Canesi seemed able to tolerate his patient’s petulance and unreliability, though his conscience soon required that he leave the dancer with his drugs and instructions, and return to Paris.

Nureyev only fitfully accepted Canesi’s advice. When given AZT, for example, he would take the pills one day, leaving them off the next if he felt better. (Ironically, this waywardness with respect to AZT might just have extended Nureyev’s life.) One thing I found rather touching and surprising was that Nureyev could deploy camp humor as a way of handling the monumental sense of loss that he experienced as his body crumbled. Asked to incline his back further at one dress rehearsal, he retorted: “Darling, the only things that I can arch nowadays are my eyebrows.” He knew that the triumphant reception he received when he danced at age 51 on the stage of the Kirov’s Marinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg was all about the symbolism, not the achievement. Still, Icarus-like, even in his feeblest attempts on stage still to matter, still to count, Nureyev proves moving. If his achievements at his zenith struck audiences as inhuman or otherworldly, his later all-too-evident fallibility restored to him some of the intrinsically representative human qualities he had lacked. In a bizarre way, his own fortunes mimicked those of Mother Russia during the long years of the Cold War.

He recognized this too: “I left USSR when the construction of the Berlin Wall had begun and returned when it was demolished—that’s a symbol, isn’t it?” It can be said of the dancer that he was “a man who stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of [his]age.” These were words used about himself by another gay artist—one whose life had a similar trajectory in some ways and whose status as myth is just as assured. Not Diaghilev or Nijinsky, but that foreign interloper in fin-de-siècle London, Oscar Wilde. Nureyev’s mantra was, “I want to do what I want,” a passable summary of Wilde’s creed in “The Soul of Man under Socialism.” For both men, inversion, paradox, and contradiction were essential to their artistic legacy as well as to their personal construction and self-understanding. Perhaps—to risk a cliché, and pace Carey—Nureyev inherited all the articulateness for which Wilde was renowned in his day. It emerged in another language entirely, of course, one without words.

References

Carey, John. “Rudolf Nureyev: The Life by Julie Kavanagh,” London Sunday Times, September 30, 2007.

Maybarduk, Linda. The Dancer Who Flew: a Memoir of Rudolf Nureyev. Tundra Books, 1999.

McCann, Colum. Dancer. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2003.

Rudolf Nureyev, Nureyev: His Spectacular Early Years: an Autobiography. Hodder & Stoughton, 1993 (orig. 1962).

Solway, Diane. Nureyev: His Life. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1998.

Souter, Carolyn. The Real Nureyev: An Intimate Memoir of Ballet’s Greatest Hero. Thomas Dunne Books, 2004.

Stuart, Otis. Perpetual Motion: the Public and Private Lives of Rudolf Nureyev. Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Van Vooren, Monique. Night Sanctuary. Summit Books, 1981.

Richard Canning’s most recent books are Between Men and Vital Signs: Essential AIDS Fiction (both Carroll and Graf, 2007) and Oscar Wilde: a Brief Life (Hesperus, 2008).