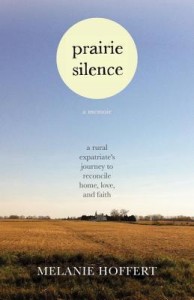

Prairie Silence: A Memoir

Prairie Silence: A Memoir

by Melanie Hoffert

Beacon Press. 238 pages, $24.95

IF IT’S TRUE what they say about everybody “having a book in them,” there’s a good chance that the book is a personal memoir. In what seems lately to be a large subset of a genre—the gay-coming-of-age literary memoir—comes Melanie Hoffert, a surprisingly Zen breath of fresh air.

Years ago, in the midst of a casual conversation with an old friend, Hoffert suddenly found herself expressing a longing to return to her childhood roots in the prairies of North Dakota. This longing had been forming in the back of her mind, but it surprised her to say it out loud. She’d hated growing up on an isolated farm in North Dakota, ten miles from a grocery store, three miles from playmates, a half-day’s drive to any major city. She had said good riddance to small-town life and the nonstop work of the farm. But sitting in a cold office in Minneapolis, she realized how much she missed the prairie and especially, inexplicably, harvest time. When the longing for home became too great, she took a leave of absence from the job she loved, deciding to dip her toes back into the land.

But in reconnecting with memories of vast openness and the kind of taciturn silence that comes when stoic neighbors are miles apart, Hoffert keenly remembered what made her flee the prairie in the first place. She knew at a young age that she was different from other girls: she figured she’d eventually kiss a boy, but she really yearned for another kind of love. She dreamed of holding hands with a woman and, to that end, she became smitten with her best high school friend Jessica, which was something she absolutely couldn’t talk about to anyone on the prairie. Still, that puppy love for Jessica changed her in ways that were encouraged by prairie mores: Jessica led Hoffert to Jesus—though Hoffert was anguished by this convergence of religion and homosexuality.

And yet, when she was able to act, however tentatively, upon her burgeoning lesbian feelings, Hoffert chose to trust the wrong person: her first encounter horrified and embarrassed her, leaving her traumatized and reaching for the comforts of home. Years after that jarring event, Hoffert, now totally comfortable with her sexuality, can share her sweet yet angst-ridden memories and her journey of self-rediscovery. Her descriptions are evocative of those cool summer nights, bonfire-and-wapatui parties with high school jocks, and cold-cut sandwiches eaten in the field on a tractor—experiences that most Midwestern farm kids are familiar with.

But there’s a sadness in this memoir, a lingering regret that Hoffert lost so much by hiding herself and her feelings from friends and family for so long. There’s also innocence and outright naïveté here: Hoffert, after all, dreamed of a chaste encounter with another woman and little more, which may make readers wonder if she really wanted now to taste life as it was, or if her experiment with farming was just a way of exploring feelings of nostalgia. Either way, readers are treated to a gorgeous book filled with quiet reverence for an unpretentious way of life, for determined self-examination, and for folks who, to Hoffert’s surprise, never really discouraged her from being who she was.

________________________________________________________

Terri Schlichenmeyer is a freelance writer based in Wisconsin.