The Man Who Invented Gender:

The Man Who Invented Gender:

Engaging the Ideas of John Money

by Terry Goldie

UBC Press. 244 pages, $32.95

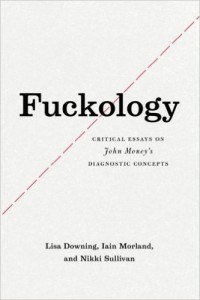

Fuckology: Critical Essays on John Money’s Diagnostic Concepts

Fuckology: Critical Essays on John Money’s Diagnostic Concepts

by Lisa Downing, Iain Morland, and Nikki Sullivan

U. of Chicago Press. 205 pages, $27.50

ADAM WAS TORN between male and female. He was born a perfectly healthy boy and grew up in a middle-class family in a small city in central California. His father was a contractor and his mother a nurse; Adam described her as an “angel.” He excelled in academics and was a star runner in high school and college—tall, lean, and blond. He was gregarious and funny, so he was equally popular with boys and girls. He dated and had sex with girls in high school and college.

But Adam had a secret side. In adolescence he had discovered internet porn. (What kid hasn’t in the past two decades?) But he had rapidly gravitated to porn with “she-males” (biological males who have breasts and a penis, and present themselves socially as female). At first it was a kinky supplement to dating and sex with women, but it grew into a more confusing and time-consuming obsession. Initially, he just fantasized that he played the female role in these porn scenes, but after a few years he started cross-dressing to get turned on. After college (and thanks to phone apps), he started hooking up with men while cross-dressed to engage in anal sex as a bottom. All the while he was still dating women. Leading a double life—plagued by guilt—was painful enough, but he also found himself squandering vast amounts of time masturbating to on-line porn or driving around trying to hook up with men. He would leave his job early or not show up at all, until he was fired. Utterly distraught and financially crippled, he attempted suicide. He was unsuccessful and promptly returned home for several months to recover. His parents were stunned and confused when he revealed his gender conundrum, but they were generally supportive—even about his decision to return to Los Angeles.

Adam soon made his way to my office. I made it clear from the outset that I had no investment in what gender or sexuality he was. I was just there to help him figure out what suited him best and how to build a happy, stable life around these aspects of his persona. It has been a rocky couple of years. Adam still enjoys dating and having sex with women, and this always reinforces his male identification. While he has tried to suppress the female side for periods, he also indulges it from time to time, but now with guilt-free pride in his feminine persona. He even tried female hormones for several months when he was convinced he wanted to change sex, but then decided against it. He realized that sex with men reinforces his femininity more than estrogen does. While Adam’s gender identity, gender role, and his sexuality remain a work in progress, he is not overwhelmed with shame and has even shared his secret with a few close friends. They have been surprised but sympathetic. Gender diversity is not so shocking to a new generation that is used to seeing transgender people, like Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner, on television.

Describing Adam’s experience requires concepts introduced by psychologist John Money (1921-2006), who is the subject of the two books under review here: Terry Goldie’s The Man Who Invented Gender: Engaging the Ideas of John Money and Fuckology: Critical Essays on John Money’s Diagnostic Concepts. Goldie is an English professor at York University in Toronto and author of several works of literary criticism and gay studies, most recently Queersexlife: Autobiographical Notes on Sexuality, Gender and Identity (2008). The provocatively titled Fuckology is a collection of essays by a troika of queer theorists: Lisa Downing, Iain Morland, and Nikki Sullivan from the disciplines of literary criticism, cultural criticism/medical ethics, and cultural studies, respectively. None of these four authors is a clinician. Goldie, however, is keenly appreciative of the clinical context for Money’s scientific publications and interweaves his own personal experiences of grappling with issues of sexuality and gender. Goldie’s book is the place to start for a broad, balanced overview of Money’s long career in sexology. His central (basically psychoanalytic) interpretation is that Money’s sexological radicalism was in reaction to his religiously conservative upbringing in his native New Zealand. Throughout Money’s subsequent career in the U.S., he countered all forms of sexual prudery and Puritanism with a call for more scientific research on sex and greater acceptance of erotic diversity.

For those already familiar with Money’s work, Fuckology provides a focused theoretical and political analysis of Money’s publications as “texts” to be interpreted. The authors’ critical essays (assaults may be more accurate) lose sight of the fact that Money was trying to help real people and allay their suffering. Money’s personality and research were certainly problematic, but he struggled to develop care for a variety of people whose medical and psychological needs had been largely ignored or stigmatized. His work spanned half a century, from the culturally conservative 1950s, through the 1960s “sexual revolution,” the AIDS era, and into the 1990s. In no small part, he fomented that revolution.

Money is widely credited with distinguishing “gender” from “sex” in his 1955 publication on hermaphroditism: the topic of his career, launching his 1952 dissertation in Harvard’s Department of Social Relations. This conceptual distinction has become so ubiquitous (primarily thanks to its adoption by feminist theorists in the 1960s) that it seems like a fact of nature. Conventionally, “sex” refers to the physical and biological traits distinguishing male and female (or other). “Gender” refers to the psychological and cultural aspects of distinguishing males and females (or other). Thanks to psychoanalyst Robert Stoller’s theorizing of “core gender identity” (one’s self-concept as male or female), Money would later distinguish “gender identity” and “gender role” (which encompasses patterns of social behavior). Money argued that that gender was culturally conditioned and not an inevitable product of biological sex.

This became the feminists’ rallying call: that “biology is not destiny,” that women’s social roles and “femininity” itself were historically and politically imposed, not the result of biology (genetics, hormones, anatomy). However, Money did not suggest that gender was free of biological influence, and he would certainly bemoan the misuse of “gender” in many medical contexts, where “gender” is substituted for the politically-incorrect “sex.”

As both books make clear, Money was embraced by feminists for decades and promoted a pro-sex message of feminism in his cherished role as public intellectual. In an array of popular publications and interviews (including for Playboy), he was an indefatigable advocate of sexual liberation—at least his version of it—which included legalizing pornography and freedom for women and children to engage in all forms of consensual erotic pleasure. In 1977, he publicly condemned Anita Bryant’s notoriously homophobic “Save Our Children” campaign to overturn a Dade County anti-discrimination ordinance. (Bryant was successful, leading to a boycott of orange juice, as she was the spokeswoman for the Florida Citrus Commission.)

From his lifelong post as professor of medical psychology at Johns Hopkins, Money published voluminously into the new millennium on his core topics: hermaphroditism (“intersex,” now “DSD/disorders of sex development”), transsexuality, homosexuality, and the paraphilias (fetishism), as well as a range of other matters, including “Negro illegitimacy,” autism, and linguistics. His later sexology books started becoming compendia of his earlier work, and even his colleagues and protégés have noted that he tended to be auto-referential, gave little room to collaborators, and rebuffed any editorial criticism. While the conceptual distinction of “gender” has been enduring, his later propensity for neologisms seems manic, particularly in the area of paraphilias. He came up with: apotem-nophilia, autoassasinophilia, paleodigm, pedeiktophilia, autogonistophilia, and (yes) fuckology (the science of sexual practices). Lisa Dowling rightly points out the parallels to the “taxonomomania” of 19th-century sexologists like Richard von Krafft-Ebing. (But the authors of Fuckology indulge in their own neologism-mania.) Money’s predilection for neo- logisms suited his repeated claims to being a pioneer in all areas of sexology, as if coining a new term, however redundant or unnecessary, guaranteed credit for a new discovery. Not surprisingly, most of his neologisms never caught on.

After the peak of his pop-cultural visibility in the 1970s and ’80s, Money returned to wide public notoriety in 2000 because of journalist John Colapinto’s As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl (HarperCollins). It was a poignant exposé of Money’s most famous case: “John/ Joan”—in reality, Bruce/Brenda/David Reimer. Bruce and his identical twin were born in 1965 in Winnipeg, Manitoba. His penis was burned off in a botched circumcision at eight months. A year later, his parents happened to see a television show where Money discussed transsexual male-to-female (MTF) surgery. The parents eventually consulted Money and followed his recommendation to surgically reassign Bruce’s sex and raise him as a girl—Brenda. Testicle removal and labial construction were done at 22 months.

In several publications, Money trumpeted the case as a success of gender reassignment: it demonstrated that gender identity could be completely molded by appropriate surgery and parenting. However, Brenda’s experience had not actually been so rosy. She had resisted a conventional feminine role, was rebellious and depressed, and fought estrogen treatment at puberty. When finally informed of her medical history at age fourteen, she reverted to a male gender role and identity as David. He eventually had a phalloplasty and married a woman. After the suicide of his twin brother in 2002, and facing separation from his wife, David committed suicide in 2004. Colapinto’s reporting on the case coincided with the rise of a political intersex movement (which I have been a part of). In addition to shifting terminology from “hermaphrodite” to “intersex,” advocates lobbied doctors to fully inform intersex patients and their parents and to defer non-urgent genital surgeries until the child can assent to them. Colapinto’s book presented Money as a clear villain who advocated a simplistic position that gender identity can be reshaped willy-nilly by surgery and child-rearing.

Money’s views on hermaphroditism were far more subtle, and he always took into consideration biological factors. However, he argued there were specific time periods during development from conception through adolescence when biological and psychological factors might be malleable before gender identity and sexuality become fixed. Hermaphrodites had been his foundational cases for testing out this hypothesis, leading to a treatment model of neonates with ambiguous genitalia that favored an early, unambiguous medical decision about ideal sex of rearing. In intersex cases, the medical team considered future fertility and genital functioning in deciding on the sex of the child and recommended the corresponding surgery to the parents to avoid any uncertainty on their part. Based on his clinical experience, Money was optimistic that if this was all done in the critical window before around eighteen months, the child’s gender identity would follow suit.

The Reimer case was doubly problematic: the child had no intersex condition, and the surgery was done relatively late. Nevertheless, Money exploited the case as an “experiment of nature” that supported his gender malleability theory. But when the experiment failed, he neglected to publish this result. Instead, a rival biologist, Milton Diamond, had to expose Money. Diamond had long opposed Money’s position, arguing that gender identity was largely determined by prenatal biological factors. Diamond doggedly tracked down Reimer, publishing the update on the case in 1997, which eventually led to Colapinto’s exposé.

Money was widely assailed by writers in the press and on-line, who often simultaneously dismissed feminism and gay studies in a broad indictment of “social constructionism.” Money’s failure to defend himself only further sank his reputation. By this time, he was starting to suffer from Parkinson’s and dementia, eventually dying in 2006. The clinical approach to intersex had already begun to move on—not only because of intersex activism in the 1990s but also because of advances in medical genetics and growing clinical experience from long-term patient follow-ups. However, as I have pointed out in these pages before (September-October 2009), many intersex cases continue to be diagnostic mysteries with significant treatment challenges. They are not just a matter of identity politics.

The general methodology of the essays in Fuckology is to examine Money’s contributions through various interpretative lenses or to apply diverse metaphors to interpreting his texts (e.g., cybernetics, sedimentation, “humanism”). I’m not convinced that this furthers our understanding of Money’s work, though it does provide an excuse for pyrotechnic displays of the authors’ queer theory skills. Some of the broader analytic points about Money’s work are obscured by theoretical jargon as his texts are fed into the queer theory sausage grinder. Most of Money’s detractors, following Colapinto’s misrepresentations, simplistically present Money as upholding gender as purely molded by the environment after birth. The three authors of Fuckology accurately explain how Money presented an “interactionist” model between “nature” and “nurture” that unfolded sequentially with shifting windows of influence. The book rightly points out that Money was a bit shifty over time about the relative importance of environment and biology, giving greater weight to biology as the scientific research accumulated. They show that despite his radicalism, Money remained a man of his time who saw sex and gender as binary: only male or female are normal outcomes.

Money was bisexual in his own behavior—or a “libertine” according to his protégé, Dr. Richard Green. However, in his publications he largely presented heterosexuality as the norm (due to reproductive and evolutionary imperatives) and everything else as a problem to be explained. Similarly contradictory was his theorizing of “normophilia” (socially acceptable heterosexuality). Money was an enthusiastic promoter of consensual kinky sex and pornographic enjoyment, even by young people. He unremittingly criticized all forms of “antisexualism,” whether from political conservatives or anti-pornography feminists (such as Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin). Paradoxically, he theorized that unrestricted enjoyment of erotica and sex in childhood would encourage “normophilia” rather than paraphilia in adulthood. But the proliferation of highly specialized forms of erotica on-line, available to any child (like Adam), does not seem to be producing a more “normal” sexual terrain; nor is kink losing its kinkiness.

Money’s endorsement of adolescent sexuality leads into that most controversial of paraphilias: pedophilia. Technically, the American Psychiatric Association defines “pedophilic disorder” as primary or exclusive erotic attraction to pre-pubescent children by someone sixteen years of age or older. Money criticized the criminalization of adolescent sexuality and moralistic, antisexual American culture. He even proposed that a sexual relationship between an adult and a prepubescent or pubescent youth might be consensual and not necessarily exploitative or abusive. His position would earn him the label of “pedophile advocate.” Ever a bundle of contradictions, in 1965 Money started advocating the “chemical castration” of repeat male sex offenders (using Depo-Provera, which would decrease or eliminate sex drive). Then as now, chemical castration remains legally and medically controversial.

Time will tell whether public and professional opinion swings back to looking favorably on John Money. As a self-proclaimed pioneer of sexual liberation he significantly contributed to the “sexual revolution” of the 1960s and 70s, but a new generation of revolutionaries turned on him as a representative of the rear guard. His prickly personality also seems to have alienated professional colleagues. Throughout the voluminous writings, the evolving and sometimes politically contradictory theorizing, I remain impressed with Money’s eagerness to wrestle with extremely complex medico-psychological cases that may not have a clear solution or be easily generalized. Each intersex, transgender, or “paraphilia” case is a unique individual who is grappling with the biology s/he was born with and the body s/he aspires to.

One’s experience of gender and sexuality is shaped and defined by culture—which can be replete with conflicting messages and values. There may not be an easy resolution to the internal confusion, contradictions, and resulting suffering that follows. Even in a sexual utopia (however you fantasize that), Adam would still struggle over whether a male or female persona was most fulfilling, or if s/he could accommodate ambivalence and fluidity. It’s one thing to claim an identity as “genderqueer” and another to live it in the real world. This still leaves the challenge of fashioning a life that is happy, productive, and fulfilling—hopefully with other people. While Money left us with dozens of new words for aspects of gender and sexuality, his core mission seems to have been a clinical one: struggling to invent conceptual and medical tools to relieve patients’ sexual suffering. We still have a ways to go.

Vernon Rosario, MD, PhD, is a historian of science and Associate Clinical Professor in the UCLA Dept. of Psychiatry. He is a child psychiatrist in the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health.