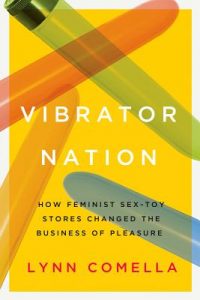

Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy

Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy

Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure

by Lynn Comella

Duke. 266 pages, $25.95

OUR BODIES, OURSELVES (1971) provided my first real lesson in sexuality—certainly more than the I Am Johnny’s Body sex education video in seventh grade or my father’s awkward “the birds and the bees” talk before I left for boarding school: “Ummm… Just avoid girls. They can be trouble.” The book epitomized the perils, pleasures, and politics of the 1970s. A small group of women calling themselves the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective pooled their knowledge and energies to destigmatize women’s bodies and sexuality. They initially produced a booklet (sold for less than a dollar) that would have been considered illegal and obscene at the time (because of the Comstock Laws). Simply depicting women’s sexual anatomy, explaining birth control, extolling female orgasm, or encouraging masturbation were all revolutionary acts of women’s self-empowerment, emancipation, and equality.

It was in this thrilling atmosphere that the feminist sex-toy business sprang up, as documented with great fondness by Lynn Comella in Vibrator Nation. Comella is an associate professor of gender and sexuality at the University of Nevada, and this book represents a two-decade project that became her dissertation in communications. Using archival materials and extensive interviews, the monograph weaves together her own experiences having worked at a sex-toy store in Manhattan with a thoughtful contextualization of the history and politics of feminism. The work is theoretically savvy without being burdened with queer theory jargon. It has a definite queer angle, not only because many of these stores’ owners and workers were lesbians but also because the heady feminist politics of the 1960s would, by the end of the century, have a profound impact on heterosexuality.

“First-wave feminism” of the 19th century relied on an image of female sanctity, sobriety, and maternal instinct to argue for the equality, if not superiority, of women in battles for suffrage and prohibition. “Second-wave feminism” of the ’60s had to undo that puritanical image when claiming the legitimacy and autonomy of female erotic pleasure. Comella rightly highlights Betty Dodson as a pioneer of feminist consciousness-raising thanks to her championing of the beauty and erotic potential of women’s bodies. Trained as an artist, Dodson daringly promoted the æsthetics of female genitalia in her early paintings in 1968—around the time of better known feminist artists like Judy Chicago and Carolee Schneeman, who made the female body their cause. After a sexually unfulfilling first marriage, she and her new lover explored masturbation with an electric vibrator. By the early 1970s she was running “Bodysex Workshops” in her Manhattan apartment. Small groups of women got naked, explored their sexual experiences and attitudes, and then used vibrators to masturbate to orgasm. Her talks at feminist conferences and her publications—most notably Liberating Masturbation: A Meditation on Self-Love (1974)—made her the evangelist for feminist autoeroticism.

Dodson’s work to destigmatize masturbation also entailed debunking the notion of the “vaginal orgasm,” which psychoanalysts claimed was the hallmark of a mature woman’s engagement to (if not enslavement by) a marital penis. For Dodson’s followers, female auto-eroticism became the epitome of the personal as the political: a way not just to destigmatize the female body and orgasm but to achieve women’s autonomy more broadly. Dell Williams attended one of Dodson’s workshops in 1973 and was blown away. After an embarrassing experience at Macy’s purchasing a Hitachi “body massager,” Williams started a mail-order vibrator business. This would become Eve’s Garden in 1975, which sold vibrators and sex-positive feminist books for the “sexually-liberated woman.” Williams was also inspired by Wilhelm Reich’s unorthodox psychoanalytic philosophy extolling the socially liberating power of sex and orgasm. Comella argues that Williams was always committed to feminist ideology more than to sales; this would continue to be a central tension of Eve’s Garden and the feminist sex toy stores it spawned around the country.

Good Vibrations would be the first, and probably the most successful, of these stores. It now includes nine stores in addition to on-line sales. Opened by Joani Blank in 1977 in San Francisco’s Mission District, it was as much a sex therapy resource center as a sex toy store. Blank had a master’s in public health and experience working in family planning. The store became a clearinghouse for advice on women’s sexuality and erotica. Thanks to its sex-positive staff, Good Vibrations become a locus for feminist sexuality debates around issues like pornography, BDSM (bondage and discipline, sadomasochism), lesbian butch/fem roles, and dildos.

In 1976, Bay Area feminists founded Women Against Violence in Pornography and the Media to condemn the sexism and violence of pornography. They also condemned BDSM as the eroticization of patriarchal power, even if engaged in consensually by lesbians. The response to these “anti-pornography feminists” was provided by sex-positive feminists who argued that pornography was not intrinsically sexist or a tool of the patriarchy. Susie Bright started working at Good Vibrations in 1980 and would be inspired to dive into these sexuality debates. In 1984, she and a group of Bay Area lesbians launched On Our Backs, a pro-sex magazine for “adventurous lesbians.” She would soon go on to become a nationally syndicated “sexpert” (and now blogger) appealing not just to a fringe of adventurous lesbians but a broad readership.

Many other lesbians and bisexual women would become leaders in sex-toy production and marketing, like Marilyn Bishara of dildo manufacturer Vixen Creations, and Toys in Babeland founders Rachel Venning and Claire Cavanah. Young, sexually uninhibited lesbians like “Susie Sexpert”(Bright) also coaxed the 60s generation of white, middle-class store owners to move beyond vibrators and to also sell dildos, strap-ons, BDSM paraphernalia, and porn aimed at women. Erotica entrepreneurs like former porn actress Candida Royalle (née Candice Vadala) started by marketing high-quality dildos, then went on to develop lesbian-oriented and women-oriented video erotica. (Royalle died in 2015, and her archives were acquired by the Schlesinger Library at Harvard.) Politics as much as profit coaxed the stores to reach out to women of color as well as to men.

Comella forthrightly examines many of the political and financial challenges the feminist-inspired stores tackled over the decades. The second-wave feminist store founders had to grapple with “third-wave” challenges: the place of women of color and lesbians in a predominantly white, heterosexual, bourgeois-dominated feminist movement; the role for men in the movement and as customers or employees; the inclusion of transsexual women and genderqueer people. Perhaps the greatest financial challenge these stores faced was that their mission prioritized sexual politics and education over commercial goals. Like other leftist business people (e.g., owners of food co-ops or feminist bookstores), sex store founders were ambivalent about, if not overtly hostile, to capitalism. Depending on the store, this attitude eventually led to financial ruin, adoption of a professional business model, or selling out to larger, non-feminist corporations.

Comella makes a good argument for how these feminist stores changed the business of sex shops. Their mission of sex-positivity, education, and safety for women broadly led to improvement in the quality of sex toys and the de-sleazing of sex shops in general. For example, the sex stores near the Los Angeles airport in the 1970s seem stuck in a 1970s time warp: located in seedy strip malls, packed with dusty, sticky merchandise, featuring a “peep show” in the back. Comella points out that the merchandise in these stores (like “pocket pussies” and “novelty” items) were cheap and degrading because they were meant for traveling businessmen who would soon discard them. Feminist stores had to be cleaner and more inviting. They also introduced high-quality, toxin-free silicone toys that were more durable and eco-friendly for a more discriminating and loyal female clientele. New sex stores appealing to all audiences have had to step up their game. That is evident in the Hustler Hollywood stores, which look like Gucci boutiques. Their marketing byline indeed seems cribbed from feminist stores: “an upscale, modern erotic boutique dedicated to providing a sophisticated shopping experience for the sexually curious.” It is ironic that the brand notorious for sexist, sleazy porn would have been influenced by lesbian feminists!

Equally striking is Comella’s analysis of the queering of heterosexual sexuality: that lesbian-run sex stores (and magazines) enlightened straight men to the delights of anal sex procured by their girlfriend’s strap-on. Comella doesn’t have any specific numbers by which to quantify the financial and erotic impact of feminist sex-toy stores on the “business of pleasure” in America. Nevertheless, her wide-ranging analysis is a fascinating survey of the evolving culture of sexuality in America and of a small band of pro-sex feminists who were on the front lines of the sexual revolution.

Vernon Rosario is an Associate Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UCLA and a child psychiatrist with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health.