Vito

Vito

Written and directed by Jeffrey Schwarz

HBO Films

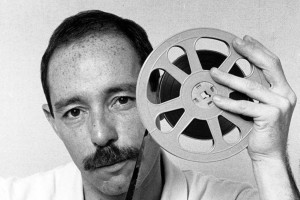

THIRTY-ONE YEARS AGO, Vito Russo published a groundbreaking study of the history of cinema called The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. The book would become one of the founding texts in the study of queer representation in the media. And, lest we forget, Russo did that work as a self-educated scholar and film buff in the era before videotape. As we learn from Vito, Jeffrey Schwarz’ important and moving documentary, Russo worked in the film archive at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the mid-1970’s. In that archive, he found one part of his life’s work.

Thanks to this powerful documentary, we now have a much more multidimensional picture of Vito Russo as activist, troublemaker, peacemaker, and lover. Russo witnessed the rioting at the Stonewall Inn in the summer of 1969, but he did not participate. However, less than a year later, he was part of the founding of the Gay Activists Alliance. He was fully committed to being part of the movement for social change, but he also wanted to have fun. Part of the fun, for Vito, was movie night, when he would show classic films of all kinds to his GAA friends and associates. Watching those films with an all-gay audience, he began to notice patterns in the kinds of scenes and characters that everyone responded to in unison. This recognition became the germ of his work as a film historian. Russo spent many years showing clips, giving lectures, and talking about the book he was writing. The Celluloid Closet was published in 1981 (revised in 1987), and it was an instant classic.

During the 70’s, Russo was a freelance journalist, publishing interviews with celebrities and writing about politics and popular culture. He developed a close friendship with Lily Tomlin, who speaks lovingly in the film about her own coming out and the ways in which Vito helped her along in that process. To make ends meet, Russo also worked the overnight shift at Continental Baths, where he became friendly with the resident entertainer, Bette Midler. He enlisted her help in the pride march of 1973, when the various constituencies—the gay men, the lesbians, and the trans folk—couldn’t get along. The documentary shows a frustrated, somewhat heartbroken Russo imploring the crowd to support and love one another—and to stop fighting. Even Bette Midler couldn’t quiet that crowd. To watch this footage from almost forty years ago is a great education for many of us who are too young to remember this era firsthand.

During the 70’s, Russo was a freelance journalist, publishing interviews with celebrities and writing about politics and popular culture. He developed a close friendship with Lily Tomlin, who speaks lovingly in the film about her own coming out and the ways in which Vito helped her along in that process. To make ends meet, Russo also worked the overnight shift at Continental Baths, where he became friendly with the resident entertainer, Bette Midler. He enlisted her help in the pride march of 1973, when the various constituencies—the gay men, the lesbians, and the trans folk—couldn’t get along. The documentary shows a frustrated, somewhat heartbroken Russo imploring the crowd to support and love one another—and to stop fighting. Even Bette Midler couldn’t quiet that crowd. To watch this footage from almost forty years ago is a great education for many of us who are too young to remember this era firsthand.

In 1983, based on the success of his book, Russo hosted a show called Our Time on New York City public television. In addition to covering news, film, and pop culture on the program, Russo also dealt with the early years of the AIDS epidemic. Some people who are not familiar with Russo the cineaste might remember him from another important documentary, the Academy Award-winning Common Threads (1989), made by Jeffrey Epstein and Rob Friedman. Russo is seen in that film as an activist and as a bereaved lover. His partner, Jeffrey Sevcik, died in the first wave of AIDS deaths in the mid-1980’s, and Russo himself was diagnosed during that time.

Vito provides significant information on the early days of the new disease, tracing it from GRID to AIDS. It also documents the emergence of glaad (the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) in response to homophobic coverage of AIDS and the gay community in The New York Post. There’s Vito Russo again, front and center, making trouble for our enemies. The activist work, including the staging of “zaps” to confront homophobia directly, laid the groundwork for his deep involvement with act up. Not long before he died, Russo made his way to Larry Kramer’s apartment, and the two men watched the 1990 gay pride parade together. The huge contingent from act up chanted “Vito!” as they moved past Kramer’s balcony. “These are our children,” said Larry to Vito. This is one of many historically significant moments depicted in Schwarz’s film.

Epstein and Friedman (of Common Threads) went on to collaborate with Armistead Maupin and Lily Tomlin to make The Celluloid Closet into a documentary in the mid-90’s. Schwartz’ film reveals how the book came to be written against the backdrop of Russo’s life, starting with his childhood in suburban New Jersey, the move to the Big City, the meteoric rise and fall. One of the funniest and saddest moments in the film occurs when the very ill Russo refuses his mother’s request that he move back in with the family so she can take care of him. Vito responds: “I’d rather die in New York than live in New Jersey.” It was Vito’s sense of humor that balanced his passionate commitment to the serious cause of gay liberation and eventually to saving gay lives. Vito is a loving portrait of a man who helped change the way many of us see the world and our place in it.