WHAT WAS “THE FIRST GAY NOVEL”? This is the theme of the latest issue of the GLR—which many of you are, I trust, happily reading. But before it came out, readers were asked which of eight novels they would select as “the first.” As reported two weeks ago in this space, E. M. Forster’s Maurice won handily with 30% of the vote, topping Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar and Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray, both of which got about 15%.

The trouble with choosing the Forster novel is that, although it was completed in 1914, it wasn’t actually published, in accord with the author’s wishes, until after his death in 1970. (The book came out a year later.) Although Maurice wasn’t available to the general public for almost sixty years, Forster would sometimes give copies of the manuscript to select friends like Christopher Isherwood, so it’s not as if the book had no audience at all while he was still alive.

And who could blame him for being so cautious? After all, Forster was still a teenager living in England when Oscar Wilde was sent to prison for the crime of sodomy. Surely the other contenders for author of the first gay novel (in English)—James Baldwin, Mary Renault, Christopher Isherwood (who finally brought Maurice to light), and the rest—would not have been as bold in the late Victorian era as they were in their own times.

But wait! There’s one contender for First Gay Novel that I haven’t mentioned yet, namely Radclyffe Hall, whose The Well of Loneliness was published in 1928. While it was written fifteen years after Maurice, Hall had the courage to publish a gay-themed novel while she was still alive, come what may. And it wasn’t as if she didn’t have literary ambitions to match those of her fellow Brit, E. M. Forster. The Well of Loneliness was her fifth novel and represents the high-water mark of her career, which never recovered from the hostile reception it received, including censorship and widely publicized court trials on both sides of the Atlantic.

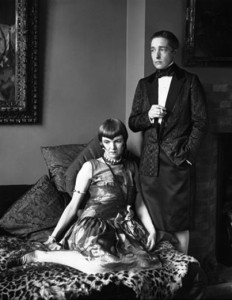

But if The Well derailed a promising career, it is only because of this novel that Radclyffe Hall is still known to us today—one of those odd twists of fame. What’s more, what seems to have hurt Hall’s reputation even more than the press’s moralistic attacks or even the trials was the string of parodies that the book inspired, starting with The Sink of Solitude. But if Hall was no literary match for Forster, at least she had the stones to do something that no one else was doing in the English-speaking world, leastwise a respected author: declare who she was and give it a name. (She called herself an “invert.”) And she posed for photographs, in full drag, with her longtime partner Una Troubridge, leaving a permanent record of her bravery.

Wendy Fenwick is an international writer based in Boston.