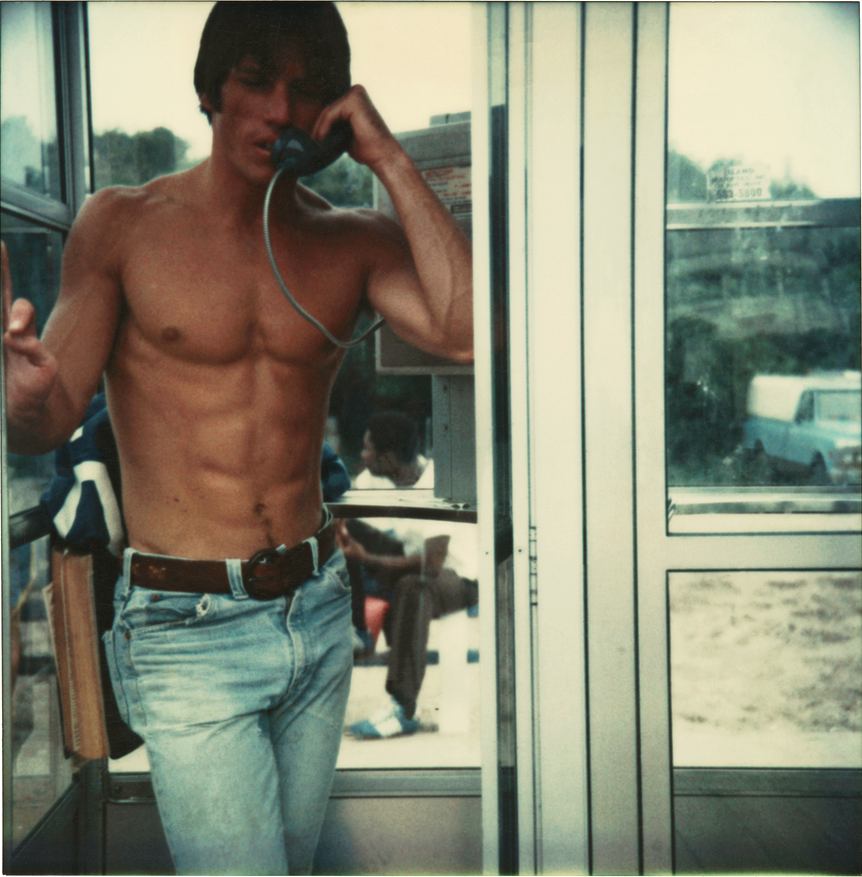

TOM BIANCHI was a corporate lawyer who fell in love with his weekends on Fire Island in the early 1970s. Fortunately for us, he turned away from his suit-and-tie life and became a photographer.

TOM BIANCHI was a corporate lawyer who fell in love with his weekends on Fire Island in the early 1970s. Fortunately for us, he turned away from his suit-and-tie life and became a photographer.

His first book, Out of the Studio (1991), displayed his photographs of beautiful gay men during an ugly time, when most cultural images of gay men were of bodies dying of AIDS, ailing, weak, and peppered with lesions. Bianchi later published an eloquent, small book called In Defense of Beauty (1995) in which he revealed that many of the gorgeous, strong men in his books were HIV positive, some of whom died not long after the images were made. His own partner had died a few months before he did that book. “Those pictures,” he wrote, “were meant to help me stay connected with what I feared I was losing forever.”

Bianchi’s latest book, Fire Island Pines: Polaroids, 1975-1983 (Damiani Books), takes us back even further, to a more idyllic time and to a storied place of glorious summers, sandy beaches, tea dances, and all the rest. But it’s not all about the past: it’s also about the community and about creating beautiful lives for ourselves and for each other.

Tom Bianchi currently lives in Palm Springs, California, with his partner Ben Smales. This interview was conducted by telephone last August.

Chris Freeman: Can you tell me how you decided to lay the book out as a weekend at the Pines? You take us from the dock, through the experience, then back to the dock in a symmetrical way.

Tom Bianchi: When I put the first version of this book together nearly thirty years ago, the material pretty much laid itself out in storyboard form. My effort had been to take the reader to the place, for the experience. When I came back to the material all these years later, I started from the beginning, revisiting the whole cache of Polaroids. I broke it down into chapters: the people, the parties, the dances. My partner Ben and I realized that it would work better as a journey, as close as possible to the actual experience. The book itself can be read as a day or as a summer. I tried to document it as comprehensively as possible. And we knew we must not lose the unusual sensuality of the place.

CF: So Ben was your first reader.

TB: Yes, and he worked with the photographs for two years before he’d ever seen Fire Island for himself. When he finally saw it, it was like time travel—thirty years in the blink of an eye.

CF: In the introduction, you set up the book when you say, “I simply wanted to tell the world that we were here and show them what we looked like.” This is what we might call a “gay pride” attitude, especially coming from that era in the 1970s when Fire Island was way ahead of nearly everywhere else. This statement also points to your whole body of work, documenting gay lives and gay life.

TB: Working on this book clarified for me that essentially I am a documentary artist, and my life is the subject. It’s overlaid with a political agenda because, really, what my life was in those days was a criminal life. We were against the law. I was attracted to the idea of the artist as outlaw—Jean Genet was the subject of my first research paper in college—but I was afraid that I didn’t have the balls to be an outlaw.

CF: Your fellow outlaw, writer Paul Monette, wrote a foreword to your first book, Out in the Studio, more than twenty years ago. He wrote, “The sumptuous geography of [Bianchi’s] imagination is a match for the dream he captures—of men at play, men at ease, men for real.” To me, this is Monette at his best, articulating the heart of your vision as an artist.

TB: It was my editor at St. Martin’s Press, Michael Denneny, who came up with the idea to have Paul write the foreword. He thought that Paul’s well-respected, critical voice would situate my work in a strong way. I only knew Paul casually in Los Angeles, and I resisted the idea because of the agony of Borrowed Time, which I had recently read and which was so painful. Because, of course, I had also just lived it myself, with my lover David. What I was really trying to do in that book was to provide an antidote to the horror of what was all around us. So I wanted to present something beautiful, something sexual. I thought, very realistically, given my own diagnosis, that Out of the Studio might well have been my first and last book. If I was going to go out in the epidemic, I’d go out with a song in my heart.

CF: What you show us in the Pines is a community, a kind of family of choice. That’s part of what made the place and the experience so special.

TB: The idea of the creation of the place as a nurturing space was really profound, and I wanted to depict that. I knew that the world would eventually move in that direction, because it was just so wonderful! I was surrounded by like-minded people, creative people, artists, visionaries. That is what we created. I wanted to show younger gay people what the world had to offer—that was very important to me. I realized that, as artists or just as individuals, we have such enormous power to shape our world. I knew the ugly side of things, not just in the ’90s but also in the ’70s. I knew about drug abuse, about alcoholism, but that didn’t have to be the material of my work, my vision.

CF: I think it’s a good thing that you weren’t able to get this book published back in the early 1980s, when you first tried to.

TB: Absolutely. Timing is everything. First and foremost, the technological advances allowed the book to be much more beautiful, more ambitious. I’m not sure I would have recognized what the best work was back then.

CF: Of course there’s the inevitable “and then AIDS hit” part of the story.

TB: The pictures stopped after the early ’80s, so that record is not part of my archive. But I wrote about it in my introduction, and I’ve written about that in my book In Defense of Beauty.

CF: There’s an kind of resonance in your book with the gorgeous, utopian ending of the 1989 film Longtime Companion, where three of the main characters have returned to Fire Island and say “Imagine what it would be like” if there were a cure. Then all the people who’ve died in the film come back for a party.

TB: Yes, I describe in the introduction walking back to the house on a more recent visit to the island. I wrote, “I was met with waves of warmth. I felt the spirit and saw the smiles of departed friends, welcoming me with a whispered ‘Glad to see you back.’ And oddly, I felt OK. I was home again.” When I first saw that scene in the film, I was amazed, because that was my experience. Living the life of a survivor, which is what I am, gives you a kind of grace or wisdom to see that we are not disconnected from those experiences or from that past. Looking back after all these years, I realize that the young man who took those pictures had a pretty simple idea about what he was doing. I wanted to do good with it, to make a beautiful portrait of my community. But in doing the book, I realized that what I had done was rather audacious.

CF: The new technology of the Polaroid SX-70 was integral to the immediacy and the success of the pictures you took.

TB: It was intended to be a casual, fun technology, not a serious tool for art, though there was an ad campaign where well-known artists, people like Duane Michals, used them. I just gave him a copy of the book. There’s a spread in the book, pages 149 and 150, which is a direct quotation of his work. I was experimenting with bringing his vision into my world and relationships.

CF: There seems to be, of late, a particular nostalgia for the 1970s. There was a recent documentary about the Continental Baths, for example, and now your book. Is nostalgia dangerous? Isn’t then always better than now?

TB: I think part of the human condition is our selective memory. Things go into soft focus as we age and need reading glasses. It can be Pollyanna, but it can also be wisdom. Why did we get upset over something so minor, say, instead of remembering and holding onto the more beautiful moments, the more meaningful ones—the astonishing moments where reality becomes sublime. Shouldn’t we be living our lives in the present, open to that recognition? I don’t see nostalgia as a negative. I see it as a positive way the mind works to remind us of what’s important. If my vision is nostalgic, dreamy, and beautiful, so be it. I like Oscar Wilde’s notion that art presents an idealized “model for being” that the world can go out and try on or try to become. The wonderful queerness of Fire Island is that it was a creative process; it was a work of art. I can imagine nothing worse than being on your deathbed and realizing you’d been afraid to live your fantasies.

CF: In some ways, what you’ve done is show the fact that many people were able to live what they imagined.

TB: Yes, we became beautiful for one another, instead of being the perverts and degenerates that society saw us as. And we did it with a sense of humor. There was a camp spirit to it, and I participated in that, taking Polaroid pictures of the life we were creating.

CF: You are not an anthropologist; you were a participant.

TB: I have never been an artist who makes beautiful objects that say “look but don’t touch.” Much of what the art world saw as beautiful did not, for me, seem true. In the Polaroids, it’s just us hanging out, doing whatever it was we were doing. I think that all of my work is a visual diary. It’s not the work of an artist trying to be an artist. That’s a lesson I learned from Duane Michals: never try to be an artist. Do your work. If it’s true, it will become art.

Chris Freeman teaches English and gender studies at the Univ. of Southern California.