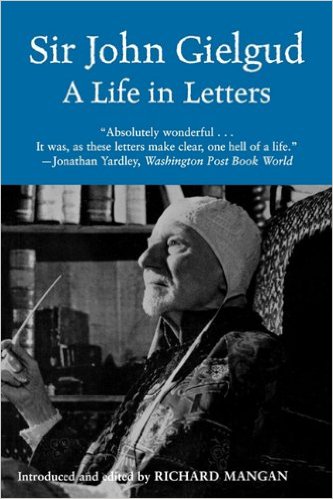

Sir John Gielgud: A Life in Letters

Sir John Gielgud: A Life in Letters

Edited by Richard Mangan

Arcade Publishing. 572 pages. $30.

SIR JOHN GIELGUD (1904–2000) was a towering figure in 20th-century English theatre, an actor to rank alongside Ralph Richardson, Laurence Olivier, Alec Guinness, Richard Burton, and John Mills. In Sir John Gielgud: A Life in Letters, theatre historian Richard Mangan has compiled reams of Gielgud’s extant letters from 1912 to 1999, which offer a one-sided conversation with everyone from Martin Hensler, Gielgud’s longtime lover, to Judith Anderson and Noël Coward.

Gielgud was vastly invested in the theatre, forever conversing about it in his letters, and he was on intimate terms with everybody who was anybody. He was a born critic of other actors’ performances, as well as his own. Well-informed and opinionated, he didn’t hesitate to go against common opinion. He believed, for example, that Audrey Hepburn was a better Eliza Doolittle in the movie version of My Fair Lady than was Julie Andrews on stage. He found it difficult to praise the esteemed British actress Gladys Cooper, but he was immensely fond of Peggy Ashcroft, with whom he shared something in common: after decades of brilliant interpretations of Shakespeare, Chekhov, Wilde, and Shaw, both achieved their greatest fame when Hollywood began to feature them in popular movies. Gielgud is perhaps best remembered for his role as the deadpan butler in 1981’s Arthur. Ashcroft had a more fleeting episode of Hollywood idolatry in the 1980’s with her Oscar-winning performance in A Passage to India.

A Life in Letters offers an auxiliary pleasure through its mundane recollections of an unapologetic gay man navigating the social waters of 20th-century London, New York, and Hollywood. Gielgud would have been a good role model for New Jersey governor Jim McGreevey and all other gay men who wait until their middle years to acknowledge their sexuality. He faced his gayness at an early age and never looked back. His biography may even invite another look at the now all-but-silenced argument against assimilation. Gielgud had a dazzling life and career full of love and success, and he never once wanted to get married, adopt children, or join the army.

With his great intellectual and creative resources, Gielgud exhibited no evidence of 20th-century gay self-hatred. He was what American psychologist Evelyn Hooker called the well-adjusted homosexual who knew how to have fun—and knew that his sexual orientation could be used with glee to create scandal among polite society. On a 1955 trip to Germany he wrote, “Tony Ireland picked up our taxi driver, a cream-faced loon dressed entirely in leather. I trembled and shook, but he turned out to be quite a dear, intensely sentimental, and never left our sides for three mad evenings. Their young men are certainly attractive, and of course they are mad costume and uniform fetishists, so my eye was continually titillated with corduroy, breeches, jackboots et cetera!”

He could be lewd: in assessing Louis Jourdan’s performance in Gigi he speculated that the actor “appears to have a big one.” He could be self-deprecating: on a trip to Spain, he reported “much rich food and vino. I shall have to be very strong-minded or return as Robert Morley.” He could be pithy: on casting a 35-year-old Olivia de Havilland as Juliet, he wrote simply, “Lunatic.” And he could be gracious and even thoughtful: to an ill Laurence Olivier he wrote, “It was wonderful of you to take the trouble to write. You must know how greatly I marvel at your endless courage and resilience despite the wretched inconveniences and setbacks you have endured these last years.”

Mangan writes the briefest of introductions and provides quick facts to contextualize Gielgud’s letters. Otherwise, it’s Gielgud’s epistolary tour de force that carries the burden of the book’s 500-plus pages. This is both an asset and a liability of this volume. There is a certain frustration in hearing Gielgud’s side of the conversation only, similar to eavesdropping on someone’s cell phone conversations. But many of the letters stand on their own and read like speeches that one can imagine being delivered by Gielgud in his distinctively rich, mellifluous voice. In the end it is Gielgud the actor who lives again in these letters.

Matthew Kennedy is the author of Edmund Goulding’s Dark Victory: Hollywood’s Genius Bad Boy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004).