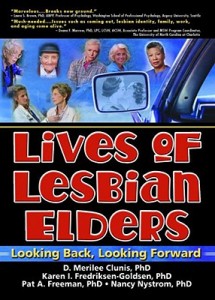

The following excerpt is the Conclusion to a new book entitled The Lives of Lesbian Elders: Looking Back, Looking Forward (Haworth Press), which describes the four authors’ research on older lesbians in the U.S. They interviewed a total of 62 women living in California, Oregon, and Washington and ranging in age from 56 to 95. An open-ended questionnaire yielded a qualitative portrait of the women’s lives now and in their earlier years, providing a window onto the “bad old days” prior to Stonewall and the gay and lesbian rights movement.

The following excerpt is the Conclusion to a new book entitled The Lives of Lesbian Elders: Looking Back, Looking Forward (Haworth Press), which describes the four authors’ research on older lesbians in the U.S. They interviewed a total of 62 women living in California, Oregon, and Washington and ranging in age from 56 to 95. An open-ended questionnaire yielded a qualitative portrait of the women’s lives now and in their earlier years, providing a window onto the “bad old days” prior to Stonewall and the gay and lesbian rights movement.

AN INTERGENERATIONAL REALITY permeates the lives of the lesbian elders in this study and marks their place in the world. With their years came a sense of being truly settled in the present, yet they acutely understood the need for change in the future. Deeply satisfied with their lives and with being gay, the women were vibrant, diverse, and active. Through their resilience, they brought an adaptive flexibility and resourcefulness to creating successful and gratifying lives for themselves and for those they love.

The importance of the generational and historical context of these women’s lives cannot be overstated. Understanding the periods during which the women came of age and first recognized their lesbianism is essential because their history continues to shape their lives today. For all the strengths and capabilities of the women we interviewed, they remain a largely invisible population in large part due to the historical conditions under which they came of age.

As highlighted throughout our research, the women came of age at a time when homosexuality was severely stigmatized and lesbian invisibility reigned. There were few public portrayals of lesbian life, and those that existed depicted a life of despair, shame, and loneliness. Mainstream society’s attitudes largely governed the language the women used to describe themselves and their beliefs about how they were supposed to live their lives.

The women’s orientation to life, to being gay, to being part of a community, and to aging differed depending on their age. The lives of those in their seventies to nineties who had lived a gay life at a relatively young age tended to be cloaked in silence. Most accepted the public code of silence without question. Some went even further; they adapted to the repression of the era by “blending”: never mentioning or discussing their sexuality, even with one another. As one woman reminisced, “I haven’t talked about it. … When I found partners, we never talked about it—ever. Blended in, never discussing anything.”

Although these women generally had few avenues available for meeting other lesbians, they talked of their “liaisons” or the “friends” they had met ever so discreetly and, in some cases, they then went on to grow old together. Most of them recognized an increased level of social acceptance, but the majority made it clear that the closet door that had never opened would remain shut. Despite tremendous risk and all the societal pressures of the times, a few of these lesbian elders—rebels, really—refused to hide or to deny their lesbianism even in the very early years.

Many of the younger women—those in their mid-fifties and sixties—who had come out to themselves early in life talked of having lived a “double life.” They came of age during a period of severe repression, when gays were publicly humiliated and persecuted. It was also a time when more avenues existed for women to meet one another including at clubs, bars, and on sports teams. With the opportunity to meet others, however, came the risk of discovery. Many lived separate gay and straight lives. They maintained a public image of heterosexuality at work and in straight society, and lived an underground lesbian life after work and on the weekends. It was important that their private lives never be made public.

Among those who had self-identified as lesbian much later in life, many were aware of their lesbian “tendencies” at a younger age but repressed them. Often they were scared; they desperately did not want to be gay so they sought safer avenues such as marriage and motherhood. The lives of those who tried not to be gay were often marked with adversity. Some sought to escape their pain through alcohol and drug abuse or suicide attempts. If they sought help, their needs were met most often with ignorance and disapproval. They were told their homosexuality could be cured or that it was just a “phase” to be ignored and disregarded.

The women in their mid-fifties to sixties who became aware of being gay much later in life often found more support in assuming a lesbian identity. Many of these women came out within the context of the women’s and gay liberation movements in the late 1960’s and 1970’s. Both the gay liberation movement and the women’s movement provided social support and a social context that countered the homophobia of the previous fifty years. With increased cultural acceptance came added social support. Even when seeking professional help, many of the women found new levels of acceptance and assistance to live their lives. For the majority of the women in this study, however, it was too late. Their secrecy and denial were so ingrained that despite societal changes and more accepting attitudes, they were not comfortable with the increased visibility—and perceived vulnerability—that accompanied coming out.

Despite age differences, all of the women shared the reality of being different, and each had to struggle to varying degrees to come to terms with her own identity. While sexual orientation was a primary aspect of personal identity for most of the women, many also talked of the importance of other identities, such as their racial and ethnic heritage, professional identity, and their spirituality. With resiliency and resourcefulness, they all faced a similar paradox in their daily lives: there was a cost to being themselves and a cost not to being themselves. This situation created the conditions for contradiction, compromise, adversity—and strength.

Once they accepted being gay, most talked of experiencing a deep sense of relief. Some described a feeling of coming home and finally achieving a sense of belonging. As one woman shared, “It was like coming from the stage of the cocoon to a butterfly. It’s a process. It’s like from one way of being to another way of being. And more than that, though, it was to know who I was—really know who I was for the first time. It was like an ‘aha!’” The women traveled unique paths to self-acceptance, The particular journey each woman walked was influenced by a number of factors, such as her individual temperament and personality, the historical context when she first recognized her lesbianism, her life circumstances, the support she received, and the critical turning points she experienced in life.

The overwhelming influence of the family and the broader culture was evident in the women’s stories. Early life experiences exerted a powerful influence throughout the lives of these women. Some parents offered encouragement, a loving environment, and promoted a “can-do” attitude. Other women were met with parental disapproval, disregard, or abuse. As the women entered into lesbian relationships, a few parents provided support; most refused to acknowledge the obvious; some completely disowned their daughters.

For the women in this study, the concept of family had evolved over time. For many of the women growing up in the 1930’s and 1940’s, norms were set for a future of marriage, children, and grandchildren. Consequently, as young women most defined families simply through biology or marriage, and the majority maintained connections with family members even when this required silence and disrespect. Over time, though, many parents and other family members became more accepting of the women’s sexual orientation and their relationships. In the later years, most had buried their parents or were caring for their parents as they aged. Regardless of the relationship they had with them, the women generally came to a place of acceptance of their parents’ strengths and shortcomings. They talked about the entirety of their relationships with their parents changing over the course of time.

Now, in their later years, most identified family as those who offered support, acceptance, and love through good times and bad. Family was important to these women. The majority of them developed a dynamic yet enduring network, including partners, children, friends, relatives—a chosen family—that provided acceptance and validation. The women rarely relied on a single source of support, but rather garnered support from multiple sources. Partners were a primary source of support, with some long-term relationships spanning more than sixty years. Many had children, and motherhood and grandparenthood continued to be significant in their lives. All of the women with children showed a desire for understanding and acceptance from their children, and most felt they had strong and positive relationships with their children, as well as grandchildren.

Other important sources of support included networks of friends, church groups, volunteer groups, twelve-step programs, lesbian support groups, and various other political and community groups. The women recognized the importance of support in their lives as a key to their self-fulfillment. Without it, they may not have had the strength to be true to themselves. From such support grew internal strength—fostering self-confidence and the drive needed to overturn the barriers society placed in their way.

This was a highly self-sufficient group of women who tended to achieve personal and professional success despite the numerous obstacles they faced. The security of their livelihood was of paramount importance, and work played a prominent role in their lives. Many had lived through the Depression and for a few poverty was an overriding aspect of growing up. The women who had recognized their lesbianism early in life knew that they needed to provide for themselves. They were well aware of the reality of discrimination, and they worked hard to succeed in their working lives, not wanting to jeopardize their success through the discovery of being gay. Some used a “cover,” such as dating men, to ensure their professional successes.

Despite rampant homophobia, workplaces—including the military—provided an opportunity for women to meet one another. However, the danger of being discovered was ever present and the consequences were severe. Most of these older lesbians accepted the need for secrecy and double lives as they learned to live with the constant fear of exposure. Despite the obstacles and stresses they faced, almost all of the women reported satisfaction from their work. Some looked forward to working as long as possible, while others looked forward to retirement. A few of the women were very concerned about ever being financially able to retire.

For a great number of those interviewed, however, their working years were well behind them, and in retirement they were free to be more open about being lesbian as well as to find satisfaction in other endeavors such as volunteer work, travel, and relationships. Retirement provided an opportunity for the women to be themselves more openly and to have the time to pursue their own interests. As one woman commented, “This is the best period in my life. I feel like I can be myself and I don’t care whether people accept me or not. I’m accepted by the people who are important to me and that’s all I really care about.”

In their later years these women tended to face the joys and challenges of aging with a certain flexibility and adaptiveness. Having already dealt with a major shift in their identities, most brought resourcefulness to their older years. Long and challenging lives shone through in the women’s perspectives on aging and the future. Having confronted adversity helped position these women for their later years. They faced the reality of their aging with a certain frankness and optimism. Whether they currently were experiencing challenges or knew they would in the future, most had an ingrained sense of fortitude, knowing that they would carry on despite the obstacles they might face. As they aged and retired, many of the women found a new sense of freedom.

The women faced the reality of their own aging with both concern and hope. Their primary concerns centered on their financial security, physical health, mental acuity, housing, caregiving, and decision-making. Overall, they expressed an ardent desire to remain independent. Many of their concerns were similar to people in general as they age, but as older lesbians they also had some unique needs. They were particularly concerned about their lack of access to supportive housing, the need to ensure control over their own lives and choices, and the importance of providing legal protection for their partners and other family members. These unique needs illustrate the importance of developing appropriate and sensitive aging services in the lesbian community as well as in society at large.

The women indicated that services will need to be developed with a clear understanding and respect for their lives and choices. The lesbian elders we spoke with were heterogeneous in age, culture, ability, income, and so on. Services will need to be developed that are responsive to this diversity. The majority of these women will most likely remain independent as long as possible and refrain from receiving outside assistance in part due to a lived history of oppression and discrimination. Among those needing services, many of the older lesbians we interviewed will most likely receive services within traditional aging agencies and will not openly identify themselves as lesbian.

As we provide opportunities for these women to receive assistance, it will be possible only if our language and the services we offer are respectful and inclusive of their life experiences. We need to ask who is important to them and with whom they have shared their lives. The women may also need special assistance to ensure legal protection for themselves, their partners, and other extended family members. Such legal planning is absolutely necessary to ensure that their life choices are honored and that those they love have access during times of serious illness or disability and that their life partners are fully recognized at the time of their deaths.

The younger women we interviewed are more likely than older lesbians to be comfortable using aging-related services in the lesbian community, and will be more assertive about their needs and rights. Service providers in the lesbian and gay community will also need to receive training regarding aging issues to ensure sensitivity and appropriate assistance. In either case, access to affordable services is critical. Many of the women that we talked with simply could not afford to pay for services.

Advocacy is also necessary to change public policies to fully recognize older lesbians and their families, to provide social security disability and survivor benefits, to protect against all types of discrimination such as in employment and housing, and to ensure full access to other public benefits. Older lesbians may be one of the most vulnerable groups of the growing aging population. The aging and lesbian and gay communities need to recognize their needs and take active steps to ensure inclusion and support. It will be important to engage the older women themselves to ensure they have an active role in service development and delivery. Lesbian elders have tremendous talents to be shared and experiences to be honored.

Many of the women we interviewed faced tremendous hardships as they sought to overcome the difficulties that accompanied being lesbian in the repressive homophobic and patriarchal society of their day. Even when they experienced extreme difficulties—being disowned by parents, losing a job, enduring a military interrogation or discharge, facing the damage created by alcoholism, or surviving the death of a partner—rarely did such hardships define their lives. Rather, they became threads woven among many other life experiences. Their stories reflect their survival and even their triumph in the face of great obstacles. How did they do it?

They took control of their lives. Cultivating rich sources of support, strengthening their own internal resources, and finding a larger meaning in life helped these women triumph over the difficult times in their lives. One of the greatest sources of strength and support for the women came from within. They tended to cultivate a strong sense of self and inner strength as they faced and overcame the adversity in their lives. Others credit their relationships or their spirituality with providing essential strength and support. A few had lesbian mentors to ease the way, but most learned through individual trial and error. Their courage and tenacity in the struggle to discover and be who they are cannot help but inspire our respect and admiration. They did what needed to be done to be independent and to accomplish their goals. They are all survivors and, generally, they are proud of who they are.

Many of the women had faced turning points in their lives that helped them to better know themselves and their place in the world. For some, these key events occurred when they were young; for most, they happened later in life. Important turning points included facing serious illness, recognizing mortality or impending death, or surviving the death of a loved one. Many of the subsequent life changes related to how the women found meaning in their lives. Some reported that facing serious illness or death compelled them to clarify what is most important in life. Despite the pressures and the imagined as well as actual negative consequences of living as lesbians, these women persevered—loving women, seeking and finding answers to who they are, and following the rhythm of their own hearts.

Many found meaning and purpose in their lives through their relationship with God or other spiritual practices. For others, meaning was created through a commitment to their personal relationships or through community involvement—helping to build a better world. Meaning was also found in the little things in everyday life. As one woman stated, “Every day there’s something beautiful. … I think that’s the thing that’s held me together all my life, whether it’s that you see a flower or running the dog or you get to hear kids laughing or even watch the squirrels scramble in the trees out there. There’s something always that holds me and holds me up. That gives me meaning. Having the capacity to be me.”

As we move forward in our quest to consider fully the lives of older lesbians, it is time to seek more depth and move beyond descriptive, cursive accounts and to begin providing opportunities for deepening our understanding of specific aspects of their lives, such as retirement, sexuality, grandparenthood, or “widowhood,” to name a few. As we look for commonalities and shared experienced, we must not lose sight of the heterogeneity within this community. It is as diverse as it is rich in varied life experiences.

It will be important to find ways to reach out further to this largely hidden population and to make additional efforts to ensure that the diversity of the community is included in our efforts. We need to hear more from older lesbians of color, those of various religious and spiritual beliefs, and those of all abilities and disabilities. We need to develop new ways to access those who remain hidden. Those who are the hardest to reach are those we hear from the least. Their stories continue to go untold and will soon be lost to history. We need to invite them into a participatory process to ensure their stories are told and to allow our ideas and ourselves to be transformed.

Although these women developed much strength through the adversity they faced, they also knew intimately the costs of forbidden love, and many were adamant that they would never reveal their lesbianism. Yet these same women were still willing to participate in this project. Why? As elders, these women want the world to be a better place for those who follow them—for their own children and for younger gays and lesbians. These women want to contribute in building that world. Although most felt that the gay liberation movement had minimal effects in their lives, they were grateful for the positive effects in the lives of younger gays and lesbians. Multigenerational connections are needed in a community that has long been denied its history. Passing on knowledge and values is an important tool to creating a healthy community and world.

Most of the women spoke of an acceptance of both the joys and the struggles they experienced as they lived and aged. The diversity in their lives, their concerns, and their dreams reflected the range of their lived experiences. Overall, these women defied common stereotypes. Contrary to popular myth, the vast majority were satisfied, engaged in life, and enjoyed loving and supportive relationships. Their lives reflected resourcefulness, capacities and strengths forged often through hardship and adversity. Although most of the women fared well despite the difficulties they encountered, not all triumphed over the obstacles they faced. Some of the women clearly lived with deep scars created by prejudice, hatred, and oppression. Unfortunately, there are undoubtedly unheard voices—those who could not fight back, who internalized the shame and despair, who lived a life of deprivation, or who did succeed in killing themselves. The women who were the most isolated and suffered the most may be the hardest to reach. Countless other women are still trying to be something they are not, to live a lie to themselves and to the world around them.

Prior to their involvement in this project, most of the women had never had an opportunity to voice themselves publicly or simply to talk about their lives this way. In fact, many were elated that someone was actually interested in their life stories. As one woman shared, “This is so exciting that I get to contribute to my community.” All of the women had advice they wanted to share with younger lesbians, and most often their advice centered on the importance of being true to oneself. Their shared experience as lesbians brought to the surface consistent messages for women who will follow them: the importance of love, self-truth, and pride figured prominently in their advice to those who will follow. One woman recommended, “Don’t be afraid. You’re entitled to be who you are.” Another woman shared this advice: “Honesty. That’s my first thing. Being able to be yourself. Not be frightened about it, and being able to defend yourself. If you’ve got to fight, do it. Just do it.” Still another woman offered this guidance: “The universal wisdom I would give to anyone—any lesbian or anyone else—I would tell them to love themselves and to thine own self be true.”