THE FRONT RUNNER would never have been written if I hadn’t started running myself. It started in summer of 1968, in real life, when I was still married and in the closet. The husband and I made a dare with another couple our age. We were all a bit overweight and desk-bound. So we would train for a year and run in the 1969 Boston Marathon. We’d heard about the Boston Marathon, where every year a few hundred crazy old men got together and ran the 26.2 miles from the town of Hopkinton, Mass., into downtown Boston. We’d also heard that women weren’t allowed to run in this marathon. But the Age of Feminism was dawning; we would deal with that somehow.

The other woman and I both were editors at Reader’s Digest. The best time we could train together (seeking comfort in numbers) was our lunch hour. So, doggedly, every noon we would go to the ladies’ room, haul on our shorts and tennis shoes, and be off, slogging around the grounds of the corporate headquarters in Westchester County.

At first we were doing well to run fifty yards. I was 32 and my pal was about the same. It was awful to be shambling along, confronted so horribly with the reality of one’s own state of unfitness. Our colleagues watched us through their office windows and wondered if we were crazy. But we kept at it. Soon enough the fifty yards was a quarter mile…and a mile. Something wonderful was happening inside our bodies. We were actually getting fit. In a couple of months, we had to get smaller shorts, because we were losing weight.

At first we were doing well to run fifty yards. I was 32 and my pal was about the same. It was awful to be shambling along, confronted so horribly with the reality of one’s own state of unfitness. Our colleagues watched us through their office windows and wondered if we were crazy. But we kept at it. Soon enough the fifty yards was a quarter mile…and a mile. Something wonderful was happening inside our bodies. We were actually getting fit. In a couple of months, we had to get smaller shorts, because we were losing weight.

That winter, the four of us discovered that there was a whole world of long-distance runners out there—not just a few hundred crazy old men, but thousands of people: amateur runners getting together for weekend races, from the Cherry Tree Marathon in New York to the Bay-to-Breakers in San Francisco. Long-distance running had always been done at the Olympics. But popular long-distance running was where President Kennedy’s appeal for national fitness had ended up.

The Road Runners Club (RRC) of America had a chapter in New York. Sanctioned Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) races were going on right in our suburb on weekends—five and ten kilometers. Everybody else, it seemed, was aiming at Boston. A few runners took us under their wing. The first thing they told us was to ditch the tennis shoes and get real running shoes.

By then, our quartet was doing five miles a weekday, usually in the mornings before work. On weekends, ten or fifteen miles at a whack, maybe more. In the RRC, you couldn’t miss the little group of women who were going to run the next Boston Marathon. Several were serious athletes. Sara Berman was a veteran Nordic skier, while Nina Kuscsik had come in from cycling and roller derbies. Kathy Swizter had actually run the Boston in 1968, but unofficially. She narrowly escaped being hauled off the course by the guardians of the rules.

The AAU, which ran all amateur sports in the U.S. at the time, had rules limiting women’s distances. They assured us that if women ran farther than a few miles, we’d fall over dead, or be unable to have children. All of us who’d been running farther than that in training knew this was baloney. In more and more men’s races, a few women were jumping onto the course unofficially, in civil disobedience. Most race directors were sympathetic and looked the other way.

Inevitably, I felt energized by the drama and the politics and the female challenge of all this. So I jumped in with these women to help change the rules. The RRC and its outspoken president, Vince Chiappetta, supported the women 100 percent. Hot fights exploded at the AAU convention, with the union’s leadership saying that hell would freeze before they’d change the rule.

Jump forward to April 1969, and the starting line in Hopkinton. There we were, twelve women crushed in the mob of 900-plus male entrants, and news cameras everywhere. In our little quartet, the husbands had numbers pinned on their T-shirts, but we had none on ours. The race directorship had decided not to mess with us in front of the TV cameras, so we were being left alone.

As the starting gun fired, the mass of humanity surged forward like water through a broken dam. Quickly the field strung out, with the plodders falling far behind. It was a cold, rainy day, close to freezing, so I was wearing tights, mittens, and an extra sweatshirt. I had never run farther than twenty miles in training and thought to myself that the last 6.2 miles should be no big deal. After all, I ran five miles before breakfast every morning.

Along about the twenty-mile mark, slogging to the top of a long, long, long grade in the Boston course that marathoners call Heartbreak Hill, I was having my first moment of truth. Why hadn’t I run the whole distance several times in training? But I was still hopeful that I’d break four hours—not a bad time for a 33-year-old female beginner in this running game. So I kept cranking along.

But when the road finally leveled out at the top of the hill, I could suddenly see way out over the vast city of Boston to the distant tower of the Prudential Building, where the finish line was. The building was half lost in a rainy mist, looking a thousand miles away, and it hit me like a sledge hammer that I was done for. I would never get there, unless I stopped running and walked. Such a temptation… so tired. I was freezing, getting blisters, and my knees were turning to mush.

But the training habit, learned way back on the Reader’s Digest grounds, now kicked in. If you keep going, if you keep pushing, wonderful things can happen. Down the long hill I went, then along the relentless straightaway of Commonwealth Avenue (“Comm. Ave.” to locals), disappearing into that dreadful distance. The “loser’s bus” pulled up beside me. Its job was to pick up stragglers who had broken down on the course. The driver opened the door. “Get in, doll,” he said. “You’ve had it.” Refusing to throw in the towel, I finally turned the corner at the Prudential. That’s when I actually picked up my death-rattle pace a little so that I could cross the finish line looking good. A few other stragglers crossed it with me. They’d keep coming for an hour yet.

The timekeeper wasn’t supposed to tell me my time, but he did—4:20. Not bad, considering how close I’d come to quitting. But the men’s winner, Yoshiaki Unetani, had finished in 2:13.49, which was twice as fast as me. Six of the twelve women would finish. Sara Berman had been the first in. I was fourth. The next day, our colleagues rolled their eyes as my training buddy and I dragged ourselves from the Digest parking lot to our offices. The cold had seared chilblains on my thighs. A week later, both my big toenails turned blue and fell off.

FAST FORWARD to a couple of years later. I was now a veteran of various distances. Our group of women activists was making progress, as more and more race directors pressured the AAU to change the eligibility rules.

At this time I had finally reached another moment, at the top of another long hill, suddenly seeing the vista of denial where I’d been living: the searing clarity that I had to get out of my hetero marriage and be honest with myself. The fact was, I’d been running into other people like myself at the races, and we acknowledged each other quietly, subtly. There were even guarded conversations with a coach or two. I kept thinking to myself, “There are other people like me out here. There must be hundreds of us in sports. Why has nobody ever talked about this?”

In 1971, the AAU finally allowed women to run officially in the New York City Marathon. I got to wear one of those cherished numbers, and came in fourth again in the women’s division. At an RRC holiday party in 1972, I found myself in a corner talking to a former college miler, the second-best in the country. He came out to me, just like that, over two styrofoam cups of carrot juice, told me that he’d decided to give up his shot at the Olympic 1500 meter because he was tired of lying. This way, at the open amateur races, he could be out and himself. He was happy.

For days after that, I couldn’t get his confession out of my mind. Then my imagination made the next step. What if there were a runner who was determined to have it all—to be out and a gold medalist too? What if the coach was a cranky conservative, as deep in denial as I had been, and finally fell in love with that runner? What if…

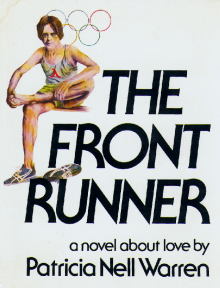

I had already published my first novel, The Last Centennial, in 1971. My agent, John Hawkins, was wondering what I would do next. Four months later, in April 1973, John and I had lunch. My heart pounding, I handed him the box of typescript written in secret, in fear and terror, on my lunch hours at work, keeping it locked in my desk at night. If I had written it at home and the homophobic husband found it, there would have been hell to pay!

So far, the only other person who’d seen the manuscript was RRC president Vince Chiappetta. I’d taken a deep breath and asked him for his opinion. He thought that in real life, it could happen just as I’d written it. “What’s it about?” my agent asked, reaching over his drink to take the box. He looked at the title, The Front Runner. “Politics?” he asked.

“Uh, sports,” I said. I didn’t have enough courage to say the word “gay.” What if my agent read it and hated it?

“I should have known,” John said, rolling his eyes.

A few days later, he called me at my Digest office. He’d read it. Heart pounding, I braced myself for possible rejection. “This is a subject whose time has come,” he said. “I don’t think I’ll have any trouble finding a publisher.”

A week later, editor Jim Landis at William Morrow offered us a contract. Shortly thereafter, I left the husband and came out. And I kept running, for a whole summer on Fire Island, discovering what “the life” was like while working on the final edit of the novel—and running a hundred miles a week. Eight miles barefoot on the beach in the morning, five miles later on the boardwalk with shoes on, still trying to better my not-too-impressive times.

In spring 1974, The Front Runner came out to controversy in the gay and lesbian world. What was a woman doing writing about gay men? I was surprised that this was an issue. There weren’t any women Olympic track coaches. Consequently, for the story to be real, it had to be about men. Meanwhile, the book got on The New York Times bestseller list—followed by the Bantam paperback a year later, and a film option by Paul Newman that never got picked up. At about that time, I had to stop running because my knees were wrecked.

FORTY YEARS LATER, the novel is still in print, out in eleven languages now. The movie is still hoped for. The Front Runner still gets fan mail every week, and a new generation is reading it. Often people ask me, as The Gay & Lesbian Review has asked me, why I think the book has had such a long run.

That’s why I have to go way back and tell the story of a 33-year-old plodder having that moment on Heartbreak Hill, getting just the barest glimpse of what real athletes have to do. If I hadn’t launched myself into the “crazy” personal adventure, I would never have gotten the idea to write the book in the first place.

People often comment to me on how “real” the story seems. It took four years and running around 2500 miles—and losing a few more toenails—to begin framing the story in late 1972. Even on the plane where I operated, the personal “realness” I experienced helped me to come to distance runners and coaches with better questions about training and injuries and psyche—not to mention questions about the social perils that ring sports round, that aim to destroy anyone who breaks the ironclad rules about sex and gender.

John Hawkins was so right—the time had come. Shortly after my book was published, the real athletes started breaking into print. Football player David Kopay came out with The David Kopay Story. Umpire Dave Pallone published Behind the Mask about baseball. Indeed, sports have proven to be one of the biggest, longest battles for GLBT equality—which could explain why my novel has stayed so popular.

Some people have criticized the novel’s ending. My response is that violence lurks in many sports, driven by ideology, both on the playing field and in the stands. In many countries, all you have to do is watch a soccer match erupt into a riot, with referees and athletes being targeted by deadly assault. Here in the U.S., we are seeing more open violence in football and baseball as well. This is a terrifying paradox, in a world where Olympic sports are supposed to promote world peace. Even as the world counts down to the Sochi Winter Games, with all their potential for harm to lesbian and gay athletes and their supporters, I don’t think my 1974 story is any stranger than real life today.

Patricia Nell Warren has published eight novels and two nonfiction anthologies of her short works, of which the most recent is My West: Personal Writings About the American West. She lives in Glendale, California, and is currently working on several new books.