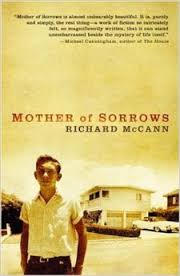

Mother of Sorrows

Mother of Sorrows

by Richard McCann

Pantheon. 192 pages, $20.

“CREATIVE NON-POETRY” is how Richard McCann half-jokingly described his unassumingly moving new book, Mother of Sorrows, at a reading. In a fusion of poetic memoir and fictional prose, McCann gently skews the facts both to guard his own past and to acquire artistic liberties. Throughout these ten overlapping vignettes, fiction becomes reality’s shadow-twin, and vice versa. McCann knows how and when to suspend the key mysteries, leaving things unsaid. His previous book, 1994’s award-winning Ghost Letters, collected his Rilkean meditations and poems on the ravages of the AIDS epidemic. Here, McCann employs similar tactics with a different thematic scope, namely the construction and disintegration of an American family.

Family is undoubtedly the overarching topic in the American literary canon, much of which focuses on the father and his torments. Decades pass under the gaze of McCann’s gay male narrator. During those years we watch his mother (whose name, Marie Dolores, translates into the book’s title) change from a glamorous young Washington-via-Brooklyn socialite to a widow wracked with worry and unexpressed grief. In the end she’s a typical older woman surrounded by her domestic bric-à-brac, “a stained-glass Serenity Prayer in her kitchen window … cut-glass dishes, filled with sugarless candies.” When her sons visit, troubled by their own burdens, she can only offer the small consolation of sandwiches and canned fruit.

At least since Freud, the bond between mothers and their gay sons has stirred up a fascinating, at times maddening, discourse. The success of recent films like Pedro Almodóvar’s All About My Mother and Jonathan Caouette’s documentary Tarnation suggests that interest in the subject is as strong as ever. But McCann’s book spends nearly equal time on the bond between gay brothers, where it’s often reminiscent of Clifford Chase’s 1995 memoir, The Hurry-Up Song. Offsetting the socially inclined (if introspective) temperament of McCann’s narrator, his brother Davis forms the darker half of this fraternal pair, eventually succumbing to an unmoored lifestyle and a drug overdose. There are allusions to Cain and Abel, but McCann avoids making them too obvious or overwrought.

McCann has an uncanny knack for remembering gorgeous details, especially when it comes to pop cultural artifacts and lost brand names like Tru-Ade, Brylcreem, and Burma Shave, which should thrill readers who came of age in the 1960’s. After devoting the first half of the book to his childhood (cross-dressing curiosities, fallout shelters, an abandoned diary), he abruptly shifts away from the suburban image of brothers trying to assemble a model of the Visible Man soon after their father’s death, and fast-forwards to forays abroad in the cities of Morocco and Europe years later in “Some Threads Through the Medina.” By means of a deft transition, McCann is able to use this juxtaposition to demonstrate just how much more internally liberated and “visible” a person he’s become. But the contrast between “then” and “now” underscores the strains in his attempts to reconnect with the past, notably with his increasingly estranged family. His path winds its way through the loss of friends and lovers to AIDS and finally to his narrator’s own HIV diagnosis, which he explores with great depth and originality in the closing chapter, “The Universe, Concealed.”

Eighteen years in the making—complications from a liver transplant delayed the writing of the book—Mother of Sorrows might have turned into quite a different book had McCann finished it years ago. Time has blessed him with the perspective to see his parents and his brother as their own people with their own lives and histories. When the narrator’s father leaves his frightened young son standing alone on the riverbank during a fishing expedition, what the narrator feels in remembering the incident is not anger or blame; instead, he writes of the father, “For whatever reasons of his own—something as simple as shyness, perhaps—he could not come to get me.”

Mother of Sorrows is redolent with forgiveness of a kind that only the passage of time makes possible. The book’s final insight is that families are merely clusters of people gathering around their deaths. Slowly, they’re overtaken by their own justifiable failings, and sometimes by the gravity of their own tenderness, as the world speeds past, changing around them.

_____________________________________________________

Jason Roush’s first book of poems, After Hours, is forthcoming.