The content of this essay was first presented at the Camp/Anti-Camp Conference at the Hau Theater in Berlin in March 2012, curated by Susanne Sachsse and Marc Siegel. The presentation of the paper was itself intended to be somewhat camp, both in the outdated academic style of the writing and in its mode of performance: The speaker wore black tails and glasses while writing lists of camp categories in chalk on a large blackboard. Whether or not the actual content of the paper was or is designed to be camp is entirely up to the reader to decide.

IN ORDER to gain a new perspective on camp, let us first re-examine some of the precepts of Susan Sontag’s seminal if problematic essay “Notes on Camp,” published in 1964. First and foremost, Sontag points out that camp is a sensibility and, more significantly, a variant of sophistication.

To start things off, and as a prime example of camp that perhaps fits outside of its “normal” definition, let us consider John Cassavetes’ film masterpiece The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. The ultra-campy emcee of the strip joint that Ben Gazzara owns and operates in the film calls himself “Mr. Sophistication.” The role is played by Meade Roberts, who wrote the screenplay for Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke, which verges on good gay camp: Geraldine Page’s mannered acting style, especially her performances in films like Williams’ Sweet Bird of Youth and Woody Allen’s Interiors, always errs on the side of camp. She also appears in Cassavetes’ brilliant Opening Night, which, I would argue, can be classified as (good straight) camp. Stages and staged performances figure prominently in both films, a particular earmark of camp, but both works also contain Cassavetes’ trademark improvisational, naturalistic, almost documentary style, a tendency that would seem to run against the high artifice and theatricality of classic camp. Therefore one could argue that Cassavetes’ œuvre generally embodies two essential qualities that paradoxically reaffirm and eschew camp, evincing a high sophistication of form that would tend to reinforce the former position.

Since Sontag

The essence of camp, according to Sontag, is its love of the unnatural, of artifice and exaggeration. She points to its esoteric nature, amounting to a private code or a secretly shared badge of identity. Further, she states that “to talk about camp is to therefore betray it,” simultaneously reinforcing and rejecting her own deep connection to the camp sensibility. She goes on to say that “to name a sensibility … requires a deep sympathy modified by revulsion,” a remarkable statement considering that her own article on camp can be considered both camp in itself (in its lofty, pretentious pronouncements) and a betrayal of it (in its sympathetic identification). Significantly, Sontag was a lesbian who had a long-term relationship with Annie Liebovitz, a purveyor, in her staged and artificial photography style, of camp, or, more accurately, bad lesbian camp. (Sontag also wrote a rather camp treatise on photography called On Photography (2001).) Sontag identifies camp as “a sensibility that converts the serious into the frivolous” (rendering her article another kind of betrayal by taking camp far too seriously), and as a matter of “taste” that “governs every free (as opposed to rote) human response.” Camp, then, is an existential condition as much as a sensibility: an enormously serious and profound frivolity.

Sontag rightly points out that camp is a certain mode of æstheticism, which is not to say beauty, but a high degree of artifice and stylization. (One could easily argue that the contemporary abandonment of the æsthetic dimension in favor of Realpolitik and mundane, conventional social issues has been disastrous to the gay experience and its formerly highly developed camp sensibility.) But her most crucial betrayal of camp comes in her statement that camp is “neutral to content,” and thereby “disengaged, depoliticized, or at least apolitical.” This is where I most strongly disagree with Sontag’s idea of camp. My perhaps idealized conception is that it is, or was, by its very nature political, subversive, even revolutionary, at least in its most pure and sophisticated manifestations.

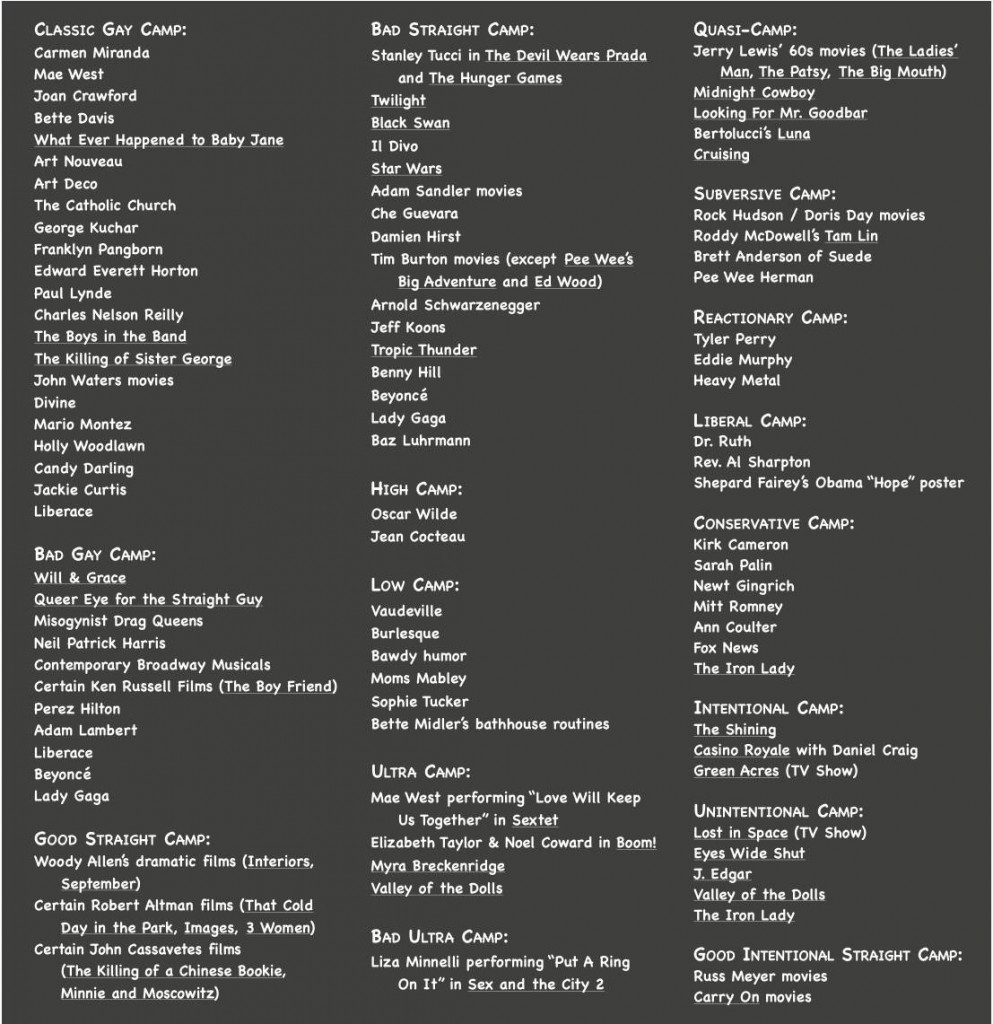

Sontag’s camp manifesto of camp was published fifty years ago, and it’s clear that it is no longer adequate to lump together all styles and modes of camp. Distinctions must be made, and the evolution or devolution of the sensibility, its movement through (accelerated) history, must be taken into consideration. I would go so far as to argue that “camp” has replaced “irony” as the go-to sensibility in popular culture, and it has, at the risk of generalization, long since lost its essential qualities of esoteric sophistication and secret signification, partly owing to the contemporary tendency of the gay sensibility to allow itself to be thoroughly co-opted, its mystery, and therefore its power, hopelessly diffused. In other words, and not to put too fine a point on it, I will argue that now, in this moment, the whole goddamn world is camp.

A critic in Harper’s Bazaar once identified irony as “the ideological white noise of the nineties,” a proclamation that always stuck with me. This wasn’t to say that irony no longer operated as a useful device or sensibility, or that it could no longer be used to subtle or witty effect. It simply meant that irony had itself been normalized and generalized into the default sensibility of the entire popular culture, thereby rendering it more difficult to detect and less effective to use unless expressed very carefully and consciously for a particular effect. The net result was that much of the general populace (now roughly equivalent to “pop culture”) had adopted the posture as a given to the extent that people generally lost track of its meaning or purpose: there was a kind of ironic detachment from everything. People started routinely to say the opposite of what they meant, and meant it, failing to understand that their new “sensibility” had become a betrayal of their actual former set of beliefs or tastes, which they even perhaps once held sacred.

So, in a sense, irony became a malaise, a kind of generalized disaffection that infected the dominant culture. I surmise that this is what opened up the floodgates for the rise of camp culture, or rather the corruption and misinterpretation of camp culture—a certain detached artificiality and forced excess which, in the wrong hands, and in its popularization, one might go so far as to call the ideological white noise of the new millennium.

Bad Straight Camp

Camp is now for the masses. It’s a sensibility that has been appropriated by the mainstream, commodified, turned into a fetish, and exploited by a hyper-capitalist system, as Adorno warned. It still has many of the earmarks of “classic camp”—an emphasis on artifice and exaggeration and the unnatural, a spirit of extravagance, a kind of grand theatricality. It’s still based on a certain æstheticism and stylization. But what’s lacking is the sophistication, and especially the notion of esotericism, something shared by a group of insiders—or rather, outsiders—a secret code shared among a certain “campiscenti.” Sadly, most of it falls under the category of “Bad Straight Camp.”

What is Bad Straight Camp? Examples would include the exaggerated and stylized streetwalker–stripper fashion co-opted by many contemporary pop music celebrities, from Rihanna to Britney and Christina on down, a performative femininity by females filtered through drag queens that has transmogrified into an arguably more “avant-garde” style (Lady Gaga, Nicki Minaj) characterized by hyper-self-referentiality, extreme hyperbole, a crudely obvious, unnuanced female sexuality, and even a vaguely pornographic sensibility which, unhappily, is post-feminist to the point of misogyny: a capitulation to the male gaze and classic tropes of objectification to be found only in the worst nightmares of Laura Mulvey. (Let it be clear that I am obviously opposed neither to pornography nor to male spectatorship per se, but rather to the continued attempt to erase all autonomy of women to control their own destinies outside of their participation in these played-out patriarchal institutions.) Obviously it’s not the form itself that is reactionary: strippers, street-smart drag queens, female porn stars, and hookers have often evinced a radically exaggerated appearance that transcends and deflects patriarchal co-optation. The problem is its utter and complete normalization and de-contextualization away from subversive or transgressive impulses in the service of capitalist exploitation, utterly heteronormative in practice and corporate in tone.

The great gay camp icons of the past—Barbara Stanwyck, Tallulah Bankhead, Marlene Dietrich, Mae West—had a sexual ambiguity that extended deeply into real life. (All were either practicing lesbians or bisexuals or, in the case of West, played with androgyny to the degree that her final performance—her autopsy—was necessary to prove her biological femaleness.) The modern gay camp icons are decidedly straight, although perversely they still attract throngs of homosexual admirers, who seem now to prefer their idols to be sexually conventional females dressed up in extreme and flamboyant style. One need look no further than battered-wife-syndrome star Rihanna or super-conventional, baby-bump exhibitionist Beyoncé, both utterly content to promote themselves tirelessly in the traditional, subservient wife and/or mother roles. (Interestingly, more contemporary camp musical icons like Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston, who most likely evinced unorthodox and “deviant” sexuality in their “real” lives, tend to come to a bad end.) The twin peaks of classic camp, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, both had disastrous relationships with their daughters, whose memoirs turned into camp classics in both cases. Nurturing motherhood and well-balanced heteronormativity have never managed to co-exist with great camp.

Other examples of Bad Straight Camp might include the genres of extreme gross-out comedy (the “Hangover” franchise, Melissa McCarthy movies); certain instances of torture porn (the horror genre has largely been infused now with a camp sensibility, whether self-consciously, such as the “Scream” franchise, or not); and last but not least, reality television, including such camp-fests as Mob Wives, the “Real Housewives” franchise, Toddlers and Tiaras, and Jersey Shore, to name only a few. (The fact that all are probably gay-friendly does little to ameliorate their general heteronormative, capitalist and materialist tenor, with the notable exception of Honey Boo-Boo.)

This new annexation and corruption of the camp sensibility now exists largely without the qualities of sophistication and secret signification that were developed out of necessity by the underground or outsider gay world, which originally created camp as a kind of gay signifying practice not unrelated to black signifying, or even black minstrelsy. It was developed as a secret language in order to identify oneself to like-minded or similarly closeted homosexuals, a shorthand of arcane and coded, almost kabbalistic references and practices developed in order to operate safely apart and without fear of detection from a conservative and conventional world that could be aggressively hostile towards homosexuals, particularly effeminate males and masculine

females. In the contemporary world, in which gays have largely assimilated into the dominant order, such signifying practices have become somewhat obsolete, and the previous forms of camping and camp identification have long since been emptied of camp or gay significance, rendering them easily co-opted, commercialized, and trivialized.

Gay Conservative Camp

This phenomenon has also led to the rise of what I call “conservative camp.” For what are Sarah Palin, Newt Gingrich, Bill O’Reilly, Donald Trump, and Herman Cain other than conservative camp icons enacting a kind of reactionary burlesque on the American political stage? Wholly without substance, their rhetoric exaggerated and stylized, evincing a carefully contrived posture of “compassionate conservatism,” they function merely as a crude spectacle that mocks the unwashed masses by pretending to be one of them while simultaneously offering them policies that are directly antithetical to their authentic needs. Conservative camp has always been around—William F. Buckley, Jr. is a prime example—but it has now become an entire genre, thoroughly entrenched and embraced by the American public.

Alarmingly, with the rise of gay conservatism, there is also another new category of camp to contend with: Conservative Gay Camp. A recent example is the Hollywood movie J. Edgar, featuring two wildly camp performances by presumably straight actors: Leonardo DiCaprio as longtime FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and his reputedly platonic lover, Clyde Tolson, played by Armie Hammer. Written by a young gay screenwriter, Dustin Lance Black, and directed by a classical heterosexual Hollywood director, Clint Eastwood, whose macho posturing has always bordered on straight camp, the film combines a serious, hyper-masculine style with a mocking, self-consciously queer contemporary sensibility that results in a strange confluence of straight and gay camp. The project of the film could be characterized as “conservative drag,” a loose reworking of Hitchcock’s Psycho that attempts to recuperate the ultra-reactionary, cross-dressing J. Edgar by presenting him as a pathetic, repressed Mama’s boy who could have been a great American hero if only he’d been allowed to have an open, sexually honest, and of course monogamous relationship with his handsome, doting right-hand man, Tolson.

This is the essence of gay conservative camp—a baroque fantasy of revisionist history that projects contemporary homosexual conservative values and morals into the past in order to recuperate and reclaim these complex, monstrously pathological characters as themselves mere “queer” victims of a repressed and homophobic society. (Judi Dench as J. Edgar’s mother telling him she would rather have a dead son than a “daffodil” is quintessentially camp.) Aside from amounting to questionably reductive pop psychology (the smothering mother, etc.), it belies the reactionary impulse to attribute sexually “deviant” behavior—cross-dressing, extreme aestheticism, dandyism—to a negative consequence of corrupt and oppressive systems, as opposed to instances of rebellion and revolt and a healthy acting out against such regimes. In other words, such “deviance” wouldn’t be necessary if only the system were liberalized and reformed to reflect a healthy, normalized, and assimilated homosexuality, one that is indistinguishable from the heterosexual status quo save only for its preference for same sex partners—in a word, “homonormativity.”

This kind of conservative camp tends to ignore or revise historical and political context in order to bolster its recuperative project; other recent examples would include, in post-feminist terms, The Queen and The Iron Lady. This new tendency runs in diametrical opposition to the impulses of classic gay camp, which sought to celebrate, elevate, and even worship the qualities of deviance, difference, and eccentricity that characterized the highly æstheticized homosexual experience of past eras.

If I have expressed a rather depressing and unhopeful analysis of camp, or perhaps what might now reasonably be termed “anti-camp,” I can only offer by way of an antidote an express wish to radicalize camp once again, to harness its æsthetic and political potentialities in order to make it once more a tool of subversion and revolution. Camp itself should almost be defined as a kind of madness, a rip in the fabric of reality that we need to reclaim in order to defeat the truly inauthentic, cynical, and deeply reactionary camp—or anti-camp—tendencies of the new world order.

Bruce LaBruce is a Toronto-based filmmaker, writer, director, photographer, and artist. He has directed and starred in numerous films and theatrical productions and his photography has been featured in exhibitions across the U.S. and Canada. This piece, which originated as a presentation in Berlin (see above), was first published in Nat. Brut magazine (www.natbrut.com), Issue 3 (April 2013).

Discussion1 Comment

Pingback: Reflections on My Year as a Windy City Empire Duchess – Imperial Windy City Court of the Prarie State Empire