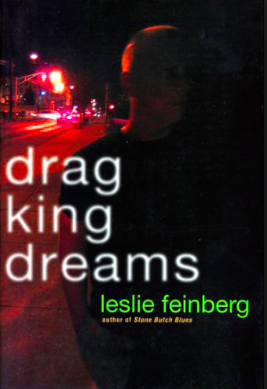

Drag King Dreams

Drag King Dreams

by Leslie Feinberg

Carroll & Graf

302 pages, $15.95 (paper)

NEW YORK WINTER, in the early dawn: a man and a woman exit a PATH train and stand on the crowded platform. They have worked at an all-night club and are heading to their respective homes. The train, crowded with New Yorkers on their way to work, has been the scene of a frightening encounter. Through the windows as it moves out, the couple watch the trouble-maker, who has been unable to escape the crowded train. Max and Vickie talk quietly, and finally Vickie says, “Go home, Max. Go to bed.” Vickie gets on the next train, and Max takes the steps to the street, ducking his head against the cold New York wind. He pulls the brim of his cap down and tugs up his scarf, and thinks, “There is safety in cold like this.” Yet this is the last time Max will see Vickie alive. She is murdered on the last leg of her trip home.

This might be the first scene of a mystery. But, as it turns out, the police do not investigate this murder. No one does. In a post-9/11 New York, undesirables frequently disappear. In fact, the police are often the perpetrators. Max and the rest of the people who populate Leslie Feinberg’s latest novel live on the fringes of society. Paid every morning in cash—Max doesn’t even have an I.D.—treated poorly by his employer, Max tolerates it because the places where he can work are limited. What’s more, in the wake of the terrorist attacks, there are others at risk from the authorities. The electricity is still out in some neighborhoods, yet the round-up of those who resemble “the enemy” has begun.

Feinberg does an interesting thing with the political events of this period. She deftly juxtaposes the plight of Muslims, Arabs, and South Asians with the plight of the transgendered—the disappearance of Hatem, a friend and neighbor, with the death of Vickie, a transgendered performer. Then, with subtlety, she demonstrates the many ways in which the political is the personal.

Max, the first-person narrator, is a likable character. Readers might find themselves comparing him to the “stone butch” character they met thirteen years ago in Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues. But Drag King Dreams is not a sequel—not exactly. The world that Feinberg’s characters inhabit in Dreams has changed a great deal since 1993, when words like “AIDS” and “Internet” weren’t yet in the dictionary. In Max we find the downtrodden activist whose existence is fraught with danger. Immediately after Vickie’s death, his closest friend Ruby is hospitalized for a scary bout of AIDS-related pneumonia. As Ruby fights for her life, she loses her job. The rest of the group from the Star Dust club tries to make a stand for Ruby. They organize a work stoppage, and Max disappoints them by going to work anyway. When he gets there, he finds the club closed for the night. Though Max is closer to Ruby than any of the others, he can’t risk losing his own job.

Max is more mature than Jess (the stone butch). He spends more time ruminating about the past, about the death of his mother, and about a woman he loved who disappeared many years ago after Max abandoned her to escape the police. For Max, wisdom comes from Aunt Raisa, who raised him. “It’s better you should die standing up than live on your knees!” Yet Max lives in a world where even using a public restroom can result in an arrest. He tries to learn a computer game, and even that is taken away when his apartment is vandalized. He thinks about women but not with the hunger of his youth. As Ruby says, “We’ve outlived our life expectancy as drag people, you and me.”

Feinberg also does some interesting things with pronouns, using “he” and “she” according to the gender of the heart rather than of the chromosomes, and she adds “hir” and “ze” to the mix. Feinberg’s sentences are as solid as concrete blocks—no fancy syntax, no winged metaphors. Symbolism is developed through analogy. People who are hated and feared are disposable. Although radically different, the newly dispossessed have much in common with the old guard, and they instinctively know this. They fight back in the beginning, but stop as the losses mount. In a conversation with Ruby about the old days, Max says, “It seems like such a long time ago that you and I were up all night on buses going to D.C. for marches, or sleeping on church floors the night before. I was tired, but it was different then. I didn’t feel so worn out. I had so much energy, so much optimism. … The movement filled up with people who didn’t want you and me in it.” Older readers will remember that lesbians were purged from the women’s movement in the 70’s. Younger readers will find any number of places and events in which transgendered people are rejected. So the outcasts grieve losses, and sentence by sentence, block by concrete block, the shameful truth adds up.

Nevertheless, in this dark existence, Feinberg supplies a few small rays of hope: a neighbor who can be trusted, the kindly owner of the neighborhood deli, the waitress who ejects a group of teenage girls for harassing the transgendered group. And there are the networks of transgendered people who have found each other amid a jungle of fear and hatred. After the “blues” in the title of Feinberg’s first book, perhaps it is a hopeful sign that this title refers to “dreams.”

Martha Miller’s latest book is titled Tales from the Levee. For more about her writing, visit her web site at www.marthamiller.net.