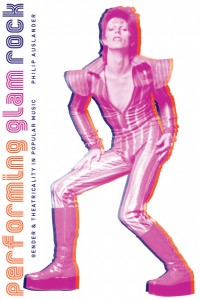

Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music

Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music

by Philip Auslander

University of Michigan Press

259 pages, $24.95

THE NARRATIVE VOICEOVER for Velvet Goldmine (1998), Todd Haynes’ film exploration of the 1970’s glam rock phenomenon, opens with the accurate words, “Histories, like ancient ruins, are the fictions of empires.” In his formidable new study, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music, Philip Auslander mines the complexly layered history of the “glitter era,” with his focus trained largely on the movement’s heightened sexual overtones. Although the actual lifespan of glam rock was brief, limited mostly to a handful of British musicians during a few years in the early 70’s, its habit of breaking traditional rules for artists’ physical appearances and vocal stylings, as well as its dramatic blurring of gender lines and performative boundaries, still have a lingering influence on today’s pop, rock, cabaret, and other genres of musical performance. Without glam rock, there may have been no heavy-metal bands in the 80’s, no risk-takers like Marilyn Manson in the 90’s, and probably no Madonna.

Auslander, a performance studies professor at Georgia Tech, resolves at the outset to distinguish his approach to glam rock: “Most of the work in cultural studies of popular music that focuses on production examines the sociological, institutional, and policy contexts in which popular music is made, not the immediate context of the work of the artists who make it.” Why have critics often avoided taking an inside look at how musical performers themselves operate? The most obvious explanation is that the performer must always remain a kind of enigma, an intentional mystery whose truth—in the interest of keeping the Oz-like magic alive—can never be fully revealed.

Though it honors both the mystery and the concealed levels of meaning, Auslander’s stance here is “unabashedly performer-centered.” He constructs his text around a close analysis of glam rock icons like Marc Bolan, David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Bryan Ferry, and one token female glam rocker, Suzi Quatro, all of whom borrowed liberally from rock traditions and from each other. While Auslander’s approach is accessible and fairly engaging (despite some occasional dry stretches of exposition), it’s hard to imagine that the bulk of this book would be entertaining for readers with no previous background or die-hard interest in glam rock. Even some glam rock aficionados might scratch their heads during Auslander’s ten-page, song-by-song dissection of David Bowie’s final 1973 concert as Ziggy Stardust, his bisexual alien persona, which includes such details as what sort of boa Bowie wore when guitarist Mick Ronson “topped” him onstage.

Auslander’s aim is at its surest when he focuses on the performative aspects of gender and sexual identity. He builds on musicologist Simon Frith’s notion that performers inhabit at least three different roles during a performance: the actual person standing before the audience, the musician’s stage persona, and the character within a song’s text.  This interplay of shifting identities is perhaps the primary objective of glam rock itself. An artist like Bowie, who initially came into the world as David Jones, continually seeks to destabilize received gender and sexual norms, and thereby prompts audiences to question their own prejudgments on these identity issues. Bowie “himself” has professed to being gay, bisexual, and heterosexual at various points in his career, reinforcing his chapter’s epigraph: “What I’m doing is theatre and only theatre.”

This interplay of shifting identities is perhaps the primary objective of glam rock itself. An artist like Bowie, who initially came into the world as David Jones, continually seeks to destabilize received gender and sexual norms, and thereby prompts audiences to question their own prejudgments on these identity issues. Bowie “himself” has professed to being gay, bisexual, and heterosexual at various points in his career, reinforcing his chapter’s epigraph: “What I’m doing is theatre and only theatre.”

Juggling identities is certainly something that most GLBT people can relate to, and it may be one reason why we’re the audience for whom glam rock has historically had the greatest appeal. Like the performers in Auslander’s study—from the impish fantasies of Bolan to the suave metrosexual leanings of Ferry to the masculinized feminine innovations of Quatro—we’ve all learned to navigate the dilemma of which face to show our audience in a given situation. Too often in queer lives, the real face is subordinate to the created persona, especially when social and familial pressures enter the picture. And how many of us have taken refuge in fictional characters at various times, whether in pop songs, films, literature, or musical theatre?

But Auslander is concerned with more than just how glam rock made a bold statement for queer people: “Glam was also about revisiting the rock and roll of the 1950’s in search of more direct and straightforward musical models than psychedelic rock offered; returning spectacle and theatricality to rock performance and spectatorship through movement, makeup, and outrageous fashions; reveling in the constructed nature of performance personae; and treating musical styles, and even specific voices, as source material to be plundered at will.” Glam rock’s history emphasized that any apparently stable reality is also culturally fabricated and fluid to some degree, an idea that continues to serve both æsthetic and commercial ends.|

Jason Roush, author of After Hours, a collection of poetry, teaches at Emerson College.