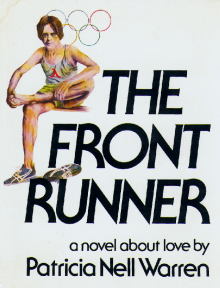

I first discovered the 1928 lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness when I was growing up in my academic parents’ house full of books. I became aware that this book had been banned in England, and I believed this was because the English legal system of the time still enforced Victorian morality, unlike the legal system in the U.S., where I was growing up “free.” I didn’t read the novel again until I was a fifty-year-old English instructor in Canada, looking for something new to say about it. I was amazed at how much the book seemed to have changed.

By the time I approached Radclyffe Hall’s controversial novel for the second time, I knew that concern for impressionable young readers (especially girls) was the usual reason given for the censorship of reading matter in various Western countries from the late 18th century all through the Victorian Age and into the 20th century. Supposedly the impressionable young were more deeply affected by what they read than most of their elders. Remembering my own responses, I could see some truth in this assumption.

Hall’s tragic story of a persecuted “invert” (essentially a lordly butch personality in a female body) who seeks social acceptance in vain never seemed like a realistic slice of lesbian life to me. What’s more, the book is written in a language that seems formal and archaic even compared to contemporary novels, and especially compared to sassy jazz lyrics of the 1920’s, which refer more openly to Sapphic love—or to be more precise, sex. The characters in Hall’s book didn’t resemble anyone I ever met in the real world. And yet, I found the story gripping.

Hall’s central character, named Stephen by her father, who insists on giving her the saint’s name he chose before her birth, is described in a self-consciously biblical style as a noble martyr who is born to suffer. She has a “Celtic” emotional sensitivity which she inherited from her Irish mother, the “fair Anna,” who reminds village peasants of the Virgin Mary. No one understands Stephen, including those closest to her, and her pain is excruciating. But never does she become hardened or bitter, since she was born to be a gentleman, and she continues wanting to offer shelter and protection to the ones she loves.

What teenager could fail to identify with a character like this? And there’s more. At age twelve, Stephen is given her own horse, and she forms a deep bond with him, promising that she will always care for him as he conveys through horsy sounds and body language that he will serve her faithfully. What an irresistible relationship for impressionable youth! This was several years before the publication of 1935’s National Velvet or the release of the movie with Elizabeth Taylor in 1944. When Stephen (the logical person to inherit the family estate from her father) falls in love with a human being, she falls as hard as any young reader could imagine. Her first girlfriend is a straight and treacherous blonde who sends a love letter she received from Stephen to the latter’s widowed mother, who banishes her only child from the family home. Such behavior looks familiar to anyone who has studied Renaissance history or survived high school.

Stephen goes on to become an earnest novelist and the chivalrous lover of an innocent orphan named Mary, whose Welsh blood gives her a “Celtic” sensitivity like Stephen’s own. The gender roles in this relationship are downright medieval, but somehow I could overlook this aspect while focusing on their mutual devotion and their adventures as a couple in the Bohemian demimonde of Paris (shades of La Bohème and its hip musical descendant, Rent). When Stephen is greeted by a queenly Frenchman in a nightclub as “ma soeur” and responds with a heartfelt “mon frère!” I was hooked. Surely there was a place in the world even for outcasts like me—never mind that my unpopularity always seemed to result more from my love affair with books than from any sign of chivalrous Celtic butchness.

While defying conventional classifications, The Well of Loneliness is typically placed in the “Young Adult” genre today. This seems quite ironic in that the publisher was tried for obscenity in the U.S.—as a book for adults—soon after being banned in England, and was only acquitted on appeal. However, the novel wouldn’t fit comfortably on a shelf with most other banned books. Those who would remove it from “lesbian literature” (where it was soundly trashed by lesbian-feminist critics in the 1970’s) and rehabilitate Stephen as a forerunner of modern transgendered characters, such as the hero of Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues, are usually embarrassed by the hagiographic tone of Hall’s narrative. Those who defend the book’s writing style as old-fashioned still have to cope with her descriptions of hereditary social class, people’s “racial” character, and the notion that gender and sexual orientation are determined by an Inscrutable Will. And then there is the grand finale, in which Stephen prays to God for mercy on behalf of her “children” and all the “inverts” of the future. Does anyone now identify as one of those?

The novel is the literary equivalent of an opera: large and loud, robustly vulgar despite its pretensions to gentility. Like opera, which I also started loving in my impressionable youth, it still has a certain emotional appeal. Should sensitive queer youths be protected from this trash for their own good, as supposedly “normal” young readers were once protected from it? Nah. I’m looking forward to a movie about the colorful author.

Jean Roberta is a freelance writer based in Regina, Saskatchewan.