Out in Paperback: A Visual History of Gay Pulps

Out in Paperback: A Visual History of Gay Pulps

by Ian Young

Lester, Mason & Begg

79 pages (illustrated), $29.95

IN 1969, in my small Montana hometown, I spotted a paperback novel on a drugstore bookrack that I knew I had to buy. The novel was Eustace Chisholm and the Works, by James Purdy. Although a blurb declared it “the sensational novel of perverse love,” what caught my attention was the cover illustration of a handsome young man, lean, muscular, arms akimbo, staring boldly at the viewer, and not just shirtless but naked, his golden torso daringly visible from his crotch upward. This cover is included in Ian Young’s wonderfully informative Out in Paperback: A Visual History of Gay Pulps.

In an essay illustrated with more than a hundred examples of paperback cover art, Young argues that gay paperbacks changed America. Purchasing Purdy’s novel certainly changed my life. The cover was the most powerful homoerotic image I had ever seen. Inside was a complex novel about tormented gay men, an early work in the career of a distinguished American writer. I barely understood some parts of the novel, but I knew this was a world where I felt more at home than I had ever felt in the exclusively heterosexual fiction I had previously read.

Young’s thesis about the significance of gay paperbacks is startling in the way it connects the dots in the history of the gay movement that emerged after World War II. The war, which put gay men and women from all over America in touch with each other and later led them to form the early homophile organizations, also stimulated a demand for small portable books that could be distributed to the troops while the war was still going on. Sales of the cheap, mass market paperbacks that resulted flourished in the postwar years. Often these were the works of unknown or pseudonymous authors dealing with less than respectable subject matter. Because most novels with gay themes were refused by hardback publishers, they appeared in these small paperback editions. As Ian Young demonstrates, from the 1940’s through the 1990’s, these gay novels both reflected and influenced changing attitudes toward homosexuality in American society.

These inexpensive paperbacks were not promoted by reviews, so publishers relied on tantalizing cover art for their adverti sing. Anyone over fifty will remember as a child sneaking a peek at the salacious covers of these books, which were sold in even the smallest towns in America. Because many of the covers depicted situations that could appear heterosexual, publishers relied on code words (“forbidden,” “strange,” “secret,” “shadowy”) to indicate gay content. For isolated gay men and women, finding such books provided their first connection to an emerging community.

sing. Anyone over fifty will remember as a child sneaking a peek at the salacious covers of these books, which were sold in even the smallest towns in America. Because many of the covers depicted situations that could appear heterosexual, publishers relied on code words (“forbidden,” “strange,” “secret,” “shadowy”) to indicate gay content. For isolated gay men and women, finding such books provided their first connection to an emerging community.

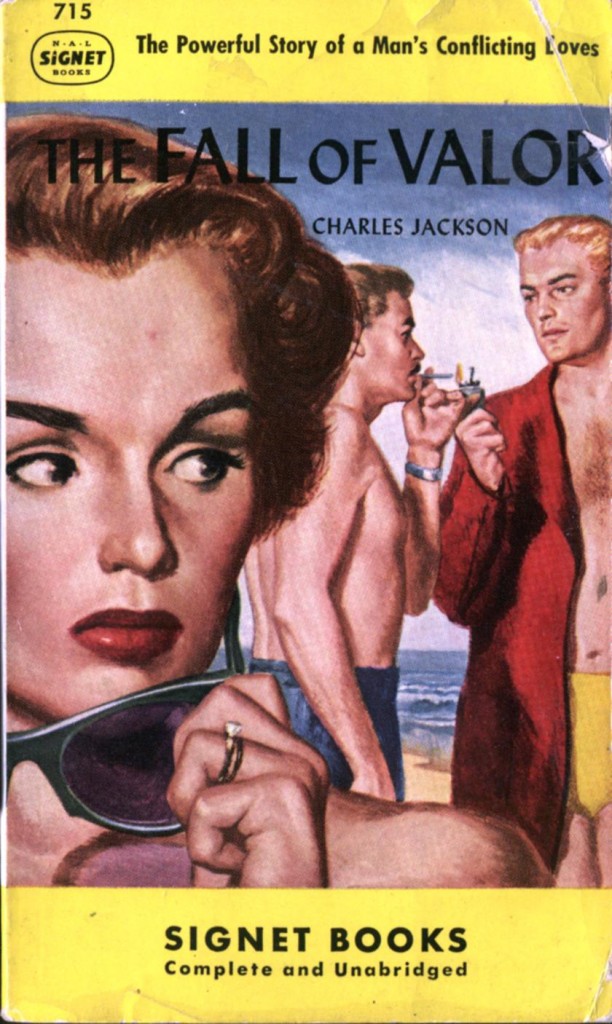

Displayed on bookracks, the covers of these paperbacks made gay men and women visible to the American public for the first time. The picture presented often conveyed multiple messages. In the decades before Stonewall it was necessary to present the negative side of this twilight world or “demimonde,” as it was called. This was done, for instance, with a trio of figures in which a woman looks alarmed about suspicious contact she’s witnessing between two men, as on the famous cover of Charles Jackson’s The Fall of Valor. On the other hand, books would better reach their intended audience if there was something attractive about the male figures, as was also the case with the Jackson cover. The woman witnesses a handsome blond man lighting the cigarette of a virile-looking man with a mustache, presumably her husband. Both men are wearing bathing suits, so their bodies can be nicely displayed.

In clear and concise prose, Young analyzes with considerable nuance the visual motifs that recurred and evolved in gay pulp cover art through six decades. One motif has proved particularly durable: two men looking away from each other, suggesting an attraction unacknowledged or denied. Young notes that this was the basis of the film poster and subsequent paperback cover for Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain.

I found Out in Paperback most interesting in the chapters on the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, when publishers and cover artists had to be somewhat subversive if they were to avoid legal challenge and still sell their books. The cover art from these years, with its dark shadows and troubled faces, often has a lurid beauty. By the 1970’s it was possible to be much more explicit in subject matter and cover art. Photographs, sometimes of the actors from the movie versions of books, appear on covers, and S&M content can now be explicitly illustrated. Covers for the Gordon Merrick’s gay romances of the 70’s are as bright and bland as the covers of their heterosexual counterparts that you see at the supermarket checkout counter today.

Young concludes his study noting that by the end of the 90’s gay literature had entered the mainstream. An intriguing cover was no longer essential to sell a book. This represented a major gain for gay writers, whose work could now be widely reviewed and sold in bookstores and on bookselling websites. Still, it is good to be reminded of this chapter in the history of gay publishing, of a time when a cheap paperback on a drugstore rack could change someone’s life.

Daniel Burr is an assistant dean at the Univ. of Cincinnati College of Medicine, where he teaches courses on literature and medicine.