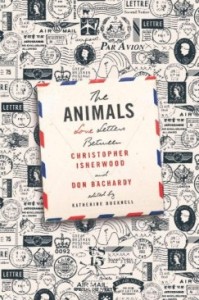

The Animals: Love Letters Between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy

The Animals: Love Letters Between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy

Edited by Katherine Bucknell

Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 481 pages, $30.

THIS EXTENSIVE COLLECTION of the letters between Christopher Isherwood and his longtime partner Dan Bachardy feels like a perfect companion volume to the excellent 2007 documentary Chris & Don: A Love Story, which told the story of the couple’s life together. Isherwood, of course, is the author who witnessed and chronicled in his Berlin Diaries both the sexual liberation of Berlin in the 1920s and the rise of fascism in the ’30s.

The two men met on a California beach when Isherwood was 49 and Bachardy was 18, and, against all odds, they stayed together for over thirty years, until Isherwood’s death in 1986. What makes their longevity as a couple remarkable is that most of their romance took place during an especially conservative and sexually repressed era. What’s more, many people looked askance at their considerable age difference.

As this volume clearly indicates, they paid little attention to the latter objection. Isherwood’s literary celebrity meant that he had an endless supply of accomplished, celebrated friends, people like Tennessee Williams, Shelley Winters, Chita Rivera, Roddy McDowall, and Andy Warhol, who come up throughout the letters. I think my favorite bit of epistolary name-dropping comes when Gore Vidal makes an appearance. In November of 1961, Isherwood writes: “Gore here for a short visit, assured me we shall visit Jackie and Jack and you shall draw them. He loves the Kennedys as much as ever and stays frequently at the White House. The word going around now is NO WAR, but the bomb-shelter racket flourishes. … [He] is terrified of fascism in this country.”

The title of the book comes from the running theme of their letters: the couple had pet names for each other, Isherwood being a gentle horse and Bachardy a fluffy cat. Depending on the reader’s mood, this will be received as either touching or cloying. They weren’t using these pet names as an elaborate code, as they lived quite openly as a gay couple; these were simply terms of endearment. However, given that they write about affairs they’re having outside of the relationship, after a while the childlike names began to evoke strange images in my head, like Beatrix Potteresque animals locked in a dungeon while wearing S/M gear. Their lives, together and apart, were anything but the stuff of kiddy lit.

One gets a strong sense of their wonderful sense of humor. Isherwood’s legendary bitchiness often shines through: at one point he refers to Southern California as a “joke in bad taste.” If there is a big surprise, it would be that even a writer of Isherwood’s status dealt with anxieties about money and how to sustain himself with an income. Also, the teaching he did at Los Angeles State College sounds at times like an unwelcome chore.

If this volume has a happy ending—and it does indeed feel like one—it’s because the letters end in 1970. That’s when Isherwood and Bachardy were finally able to coordinate their lives so they could live together, which ended the need for letter-writing. And that feels like a truly happy thing, because about one fifth of their letters are pronouncements about the agony of being apart—lengthy, gushing tracts given over to poignant, long-distance longing. In February 1965, Bachardy writes: “Kitty is so lonely and sad without his Dear, now. He dreamt about him all last night and I think probably cried out for him several times but there was no one to hear him. Kitty misses him so.”

Also hanging over the book, it must be sadly noted, is the anti-Semitism for which Isherwood has become known since his death. This comes up in the letters, too, where there are a few disparaging remarks about Jews. That the man who so carefully and accurately depicted the Nazis’ rise in pre-World War II Berlin held bigoted views is truly disturbing. But Isherwood fanatics (and I count myself among them) will want to read this book. The Animals evokes the mixed series of feelings one would have after rummaging through a large box of old letters from a very dear and complicated friend who’s no longer around: joy, sorrow, melancholy, delight, relief, and a tinge of disappointment.

________________________________________________________

Matthew Hays teaches film studies at Concordia Univ., Montréal.