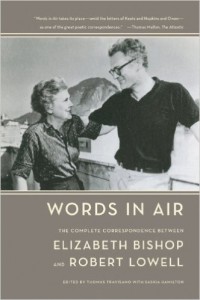

Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell

Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell

Edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton

Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 928 pages, $45.

IN THE REALM of 20th-century American literature, the collected correspondence of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell is among the most important sets of letters that we have between two poets. With style, humor, and candor, Words in Air charts the pair’s gradual rise to fame in the literary world over thirty years, from their initial meeting at the New York apartment of poet-critic Randall Jarrell in 1947, until Lowell’s sudden death from a heart attack in the back of a New York taxicab in 1977. At nearly 1,000 pages, this massive new volume will no doubt be an invaluable resource for scholars. It’s also surprisingly entertaining for anyone interested in the daily minutiae and detailed observations of Elizabeth and Cal (as Lowell was affectionately called by friends).

Because Bishop and Lowell were so central to their generation of writers, their lifelong correspondence serves as an exhaustive index and barometer of the writing community of their time. Hardly any name of literary merit in the era goes without mention here, and many of their closest connections reappear throughout the book—Marianne Moore, T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, Theodore Roethke, James Merrill—as well as those from the slightly younger generation of poets like Adrienne Rich, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Seamus Heaney, Frank Bidart, and Lloyd Schwartz.

As with any group of artists, some juicy gossip, spiked with sharp opinions, figures prominently in the letters as well. One particularly revealing exchange about the Beat poets arises after Allen Ginsberg, his boyfriend Peter Orlovsky, and their friend Gregory Corso pay a surprise visit to Lowell’s stately Marlborough Street home in Boston in 1959. Lowell remarks on the incident: “They are phony in a way because they have made a lot of publicity out of very little talent. But in another way, they are pathetic and doomed. … There was an awful lot of subdued talk about their being friends and lovers, and once Ginsberg and Orlovsky disappeared in unison to the john and reappeared on each other’s shoulders. … I think they’ll die of TB.”

Lowell was much more supportive of Bishop’s relationship with her partner of sixteen years, Lota de Macedo Soares, with whom Bishop shared a home in Brazil from 1951 until Lota’s suicide in 1967. Lowell considered Bishop’s partner to be family, and he even closed many of his letters with an endearing “Love to Lota.” That affection was complicated somewhat by Lowell’s own early romantic attraction to Bishop, an attraction that haunted him for years thereafter. In a telling 1957 exchange that has become their most infamous, Lowell, during the second of his three marriages, admits to Bishop: “I suppose we might almost claim something like apparently [Lytton] Strachey and Virginia Woolf. … But asking you is the might-have-been for me, the one towering change, the other life that might have been had.” In her reply Bishop entirely ignores Lowell’s belated confession.

Almost two decades later, Bishop’s own reminiscence of her first meeting with Lowell back in 1947 explains why her attachment to him was perhaps more like the protective sort that a sister might feel for her scruffy younger brother: “What I remember about that meeting is your dishevelment, your lovely curly hair—and how much I liked you. You were also rather dirty, which I rather liked, too.” Although both writers struggled with depression, alcoholism, and hospitalizations throughout their lives, Bishop remained the calmer, steadier presence through their correspondence; they saw each other in person only a handful of times after 1950.

Significantly, this vital difference in their personalities is reflected in their poetry itself. When commenting on the masterful intensity of the manuscript for Lowell’s book Life Studies (1959), Bishop mentions that “the whole purpose of art, to the artist [is]that rare feeling of control, illumination—life is all right, for the time being.” Lowell published, at a frenzied pace, eleven hefty volumes of poetry in his lifetime, whereas Bishop published just four slim, painstaking books by comparison. While Lowell’s poems often swerve from focus to distraction, Bishop’s poems are almost never distracted. In a 1964 letter, Lowell metaphorically describes his state of mind as “like swimming across a pond littered with pieces of wood; one wonders if one has the energy to push through it all.” Bishop—an “unerring Muse,” as Lowell himself referred to her in a poem—responds: “My passion for accuracy may strike you as old-maidish—but since we do float on an unknown sea, I think we should examine the other floating things that come our way very carefully; who knows what might depend on it?”

Jason Roush, author of After Hours and Breezeway, teaches at Emerson College.