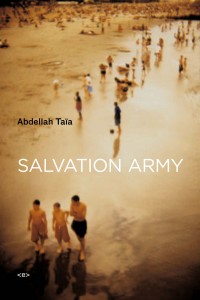

Salvation Army

Salvation Army

by Abdellah Taïa

Translated by Frank Stock

MIT Press. 152 pages, $14.95

MOROCCAN EXPATRIATE Abdellah Taïa has spent the last eight years in France, writing, acting in films, and living the dream of being an intellectual in Paris. The jacket copy for Salvation Army broadcasts that Taïa is, or is reckoned by some to be, “the only gay man” writing about a country in which homosexuality is still a crime. Salvation Army covers the years of struggle and hardship in Morocco before Taïa came out, years spent in fear and denial, along with the internal conflict that self-discovery can churn up. Yet there’s very little of that struggle, or of any other really, to sink one’s teeth into here. For a novel showing so much potential on its face, Salvation Army falls short in many ways.

The story begins in Salé with a snapshot of Abdellah’s large family crammed into a small, ground-floor apartment, sleeping so close together that he can hear his parents making love, then fighting theatrically. Abdellah grows older and develops an intense crush on his older brother Abdelkébir. They spend a week vacationing in Tangiers with a younger brother (Abdelkébir has married and moved out of the family home by this time), and Abdellah keeps a journal. There’s a fine passage in which he describes watching his brother sleep, delineating his body in detail and with increasing desire: “My brother’s body was there in front of me all afternoon. I scrutinized it, studied it from head to toe with the great care of a scientist dwelling on every detail. … All afternoon, I swam inside this body, completely unaware of how it had entertained me. This body that is a part of myself and, at the same time, is another self.” Such passages sound like they could have been pulled verbatim from Taïa’s teenage jottings—as perhaps they were; in any case, he neatly captures a moment of adolescent sexual awakening and its delicate balance with reality. His brother-lust is unconsummated, but he does leave his younger brother unattended at a soccer game in order to take in a matinée with an older man who puts the moves on him in a scene that oddly recalls Midnight Cowboy.

From Tangiers the story quickly shifts to Geneva, where Abdellah has gone to study. Time shifts back and forth as he recounts a few past relationships while staying at the Salvation Army for a few nights after missing his connection with the friend-of-a-friend who was supposed to fetch him from the airport. He’s mistaken for a prostitute in a restaurant by a man who gives him his business card; the police hassle him and his very new boyfriend; he follows a man into a public toilet and comes upon a scene Joe Orton would have appreciated. Once again, the writing takes flight when the topic is lust. After being dragged into a toilet stall and worked over, this new acquaintance thanks Taïa with the gift of a fresh orange: “And I lingered a while in the stall, pulled myself together, took stock of what had just happened with this man. Afterwards, the pleasure I got from holding that orange under my nose and smelling its exquisite sweetness made me shoot again.” Alas, these two scenes are the only times that we get any sensory engagement from our tour guide, which leaves the rest of the book feeling flat and disembodied.

Abdellah wants to be a Paris intellectual and leave Morocco behind; but why? He makes it clear to the reader that he’s gay, but has he told his family? If so, it was apparently a non-issue, which is not plausible given his origins in Morocco. He mentions a passionate love of cinema; one wishes he could bring some of that interest into his writing—or anything from his everyday world—lest we feel trapped in the interior monologue that fills most of this book. It doesn’t have to be Let’s Go Morocco, but a little description of anything other than bodies would not only have added some variety, it could have given Abdellah a bit more depth as a character.

Salvation Army is Abdellah Taïa’s third book, but it’s the first to be translated into English at a time when voices from Islamic nations are only beginning to be appreciated in the U.S. If it fails to move readers on strictly literary merits, it does help to expand our picture of a sexual world that remains deeply hidden from our view.

Heather Seggel is a writer, ex-bookseller, and occasional library technician based in Northern California.