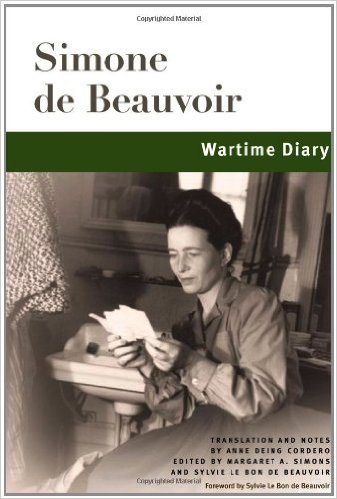

Wartime Diary

Wartime Diary

by Simone de Beauvoir

Translated by Anne Deing Cordero

University of Illinois Press. 368 pages, $40.

BETWEEN September 1939 and January 1941, Simone de Beauvoir was working in fits and starts on her novel She Came To Stay. Utterly devoted to her companion of several years, Jean-Paul Sartre, she was also devoted in almost equal measure to journalist Jacques Bost, but kept that relationship somewhat on the down-low. She entertained a few on-again, off-again girlfriends as well, all the while holding down a day job as a teacher. Juggling four or five lovers, a steady job, and a work in progress would be tricky, potentially farcical, under any circumstances; to do so in France at the start of the Second World War had to be a stretch for the 31-year-old Beauvoir, however strong her famous will and her considerable intellect.

Fortunately for us, Beauvoir took copious notes along the way, and they’ve been translated brilliantly into English by Anne Deing Cordero, giving readers a new view of the writer as well as the war. There’s much here for scholars and fans of Beauvoir’s work to digest. The affair with Bost, which she chronicled obsessively, expands the traditional view of her relationship with Sartre as the defining one. It’s clear from her entries that she loved Sartre deeply, but the same is true of her feelings for Bost. While both men were at war (Sartre was drafted in 1939 and captured by the Germans in 1940), she records countless trips to the post office hoping for letters from both, about whom she worried equally and to whom she sent care packages whenever she could. The significance of this is open to debate; at the very least we have evidence of a tremendous ability to multitask.

There’s also the matter of those female lovers, and how they change our image of Beauvoir. None of these relationships is given the same amount of ink that Sartre and Bost receive; the trysts she describes tend to be tense and fairly passionless, but they are undeniably etched in her diaries. A passage dated September 19, 1939, may offer a clue to Beauvoir’s tendency to follow all of her blisses. Written on an early morning in Paris while visiting a friend, she notes: “The weather was nice and I was … happy about this autumn day in Paris, to have found my solitude again, and about the letters I received last night. It was almost an uplifting feeling of joy, although an awkward kind of joy, because it couldn’t have a future. But how I love to live, despite everything.”

Her love of life and will to stay engaged in the present moment shine through in these diaries. While the cumulative impact of day-to-day life during the war is utterly grinding, Beauvoir enforces some domestic stability, noting where she goes to eat, on what and with whom she dines, listing the books she reads along with thumbnail reviews (“good,” “atrocious”), going to movies, and to her job as a schoolteacher as well. The very act of keeping a diary is a sort of buffer against the war, capturing the joys and sorrows of each day on the page. This quotidian rhythm is periodically broken by the harsh realities of life under occupation and war: the cafés that must drape their windows to keep the light out; a random noise that’s mistaken for an air raid siren; the presence of German soldiers in the city.

These conditions cause emotions to run higher than normal. The breakdowns that come while she awaits letters from Bost or Sartre, or fearing the worst when one does not arrive, and the almost manic highs that she experiences when a letter does come, begin to cycle back and forth in a pattern of sorts. Beauvoir describes many tearful moments that seem to wash over her in waves, though she always returns to get the details down on paper.

After parsing the relationships and romantic entanglements, the timing of these writings will give scholars another bone to gnaw. She Came To Stay has been critically summed up as a more accessible reprise of the philosophy put forth by Sartre in Being and Nothingness. As it turns out, Beauvoir’s novel was completed at about the time that Sartre was just beginning work on his philosophical magnum opus, raising the question of which came first, the existentialist or the girlfriend. Beauvoir’s influence on Sartre is probably due for a re-evaluation.

Anne Deing Cordero has done a marvelous job with the translation of these diaries, and the editing by Margaret A. Simons and Sylvie le Bon de Beauvoir (Simone’s adopted daughter and literary executor) renders the passages lucid and lively. The book seems to anticipate what a reader might need at any given moment: footnotes are kept to a minimum—much can be gleaned from the context of the entries—and when a question arises regarding a particular restaurant or nickname, a clarifying note is always close at hand.

Wartime Diary is a snapshot of a woman at a defining moment in world history, as well as a defining moment in her own career and philosophical development. The book will certainly be of interest to scholars of Beauvoir, Sartre, and their times, but it has much to offer the casual reader as well. Even someone largely unfamiliar with the life and work of Simone de Beauvoir could enjoy this book, in which one can easily get lost as in a good novel.

Heather Seggel is an ex-bookseller, currently an on-call library technician, and a reluctant novice blogger.