SOME ARE OBVIOUS, some a little less so. But trying to pin down a list of the places where the most important events in American GLBT history took place is tricky. History is personal; we all interpret it differently. But assembled here—in roughly chronological order—is a list of some of the places where the community made history. Some are jubilant and revolutionary in their evocations, some are painful to remember. But if you find yourself hankering for some gay history on the fortieth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots this summer, here are some spots where you can pay tribute to our collective past.

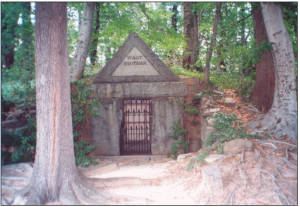

Walt Whitman’s Tomb. The American poet who wrote Leaves of Grass has yet to relinquish his  position as the nation’s greatest poet, and there can no longer be any doubt about his erotic orientation. Was Whitman in fact the first radical faerie? (Shaggy beard: check. Affinity for the woodsy outdoors: check. Debunker of organized religion and lover of pagan spirits: check. Beatific sermonizing: check.) He’s buried in a pretty, foliage-draped tomb in Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey, the city where he lived out his last two decades. Not planning a trip to Jersey any time soon? Camden is right across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, so pay your respects the next time you’re in the City of Brotherly Love.

position as the nation’s greatest poet, and there can no longer be any doubt about his erotic orientation. Was Whitman in fact the first radical faerie? (Shaggy beard: check. Affinity for the woodsy outdoors: check. Debunker of organized religion and lover of pagan spirits: check. Beatific sermonizing: check.) He’s buried in a pretty, foliage-draped tomb in Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey, the city where he lived out his last two decades. Not planning a trip to Jersey any time soon? Camden is right across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, so pay your respects the next time you’re in the City of Brotherly Love.

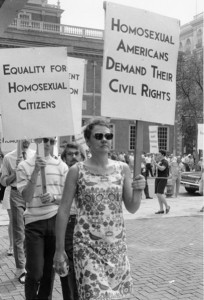

Independence Hall, Philadelphia. If you visit Independence Hall, you’ll find yourself sharing the space with tourists interested in the signing of the Declaration of Independence and all that, but  this was also the place where the gay and lesbian protest movement began. It was in 1965 that activist Barbara Gittings and a crew of conservatively dressed gay men and lesbians formed a picket line and toted signs with slogans like “Equality for Homosexual Citizens” and “Homosexual Americans Deserve Their Civil Rights.” True, similar protests (also led by Gittings) were held outside the State Department and the White House in Washington, DC, but it was Independence Hall that saw sustained picketing from 1965 all the way to 1969, when Stonewall finally stole the show.

this was also the place where the gay and lesbian protest movement began. It was in 1965 that activist Barbara Gittings and a crew of conservatively dressed gay men and lesbians formed a picket line and toted signs with slogans like “Equality for Homosexual Citizens” and “Homosexual Americans Deserve Their Civil Rights.” True, similar protests (also led by Gittings) were held outside the State Department and the White House in Washington, DC, but it was Independence Hall that saw sustained picketing from 1965 all the way to 1969, when Stonewall finally stole the show.

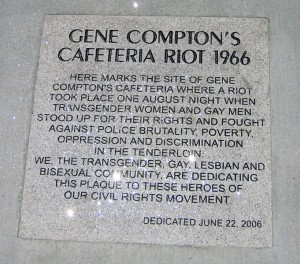

Compton’s Cafeteria, the Tenderloin, San Francisco. Not just a neighborhood eatery in SF in the 1960s, Compton’s was the home to the first transgender riot in U.S. history, predating the Stonewall riots by three years. During the 1960s Compton’s in the Tenderloin (there were other locations) was known as the safe haunt for the transgender community, as transpeople were unwelcome in the  city’s gay bars. One August night in 1966, police were called to the cafeteria when some of the transgender diners got raucous, and when one cop tried to arrest one of the drag queens, she reportedly tossed coffee in his face. The ensuing riot involved thrown dishes, vandalized police cars, and an incinerated newsstand. Tenderloin hustlers and street people joined the trannies to picket Compton’s the next night, and another riot broke out. The riots led to the founding of the first transgender activist group. In 2006, a plaque was dedicated on the site of Compton’s commemorating the riots. For more, check out the 2005 TV documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria.

city’s gay bars. One August night in 1966, police were called to the cafeteria when some of the transgender diners got raucous, and when one cop tried to arrest one of the drag queens, she reportedly tossed coffee in his face. The ensuing riot involved thrown dishes, vandalized police cars, and an incinerated newsstand. Tenderloin hustlers and street people joined the trannies to picket Compton’s the next night, and another riot broke out. The riots led to the founding of the first transgender activist group. In 2006, a plaque was dedicated on the site of Compton’s commemorating the riots. For more, check out the 2005 TV documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria.

The Stonewall Inn, New York City. Every movement has its symbolic birthplace, its Bastille or Plymouth Rock. For us, the place that’s recognized across the planet as the birthplace of the modern  gay rights movement is a little bar on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. That volatile night in late June of 1969 when things got rowdy at the Stonewall Inn has gone down in history as an event that changed the course of gay lives forever. It’s amazing to think that a crowd of scrappy young men and fed-up drag queens gathered their courage to fight back against the police in a raid, kicking off several nights of civil unrest and riots. The modern location of the Stonewall Inn is actually a U.S. National Historic Landmark. What’s more, there is still a Stonewall Inn at that same location at 53 Christopher Street, right on Sheridan Square. You can visit, have a drink, and pay homage to the people that started a revolution. The venue itself has changed hands many times through the years and has never quite managed to live up to its pedigree. Today, the club nights there tend to be a bit wonky and the crowd veers toward a random mix of tourists, city kids, and bridge-and-tunnel gays. But if today’s Stonewall Inn isn’t the coolest place in the City, that’s beside the point; what matters is what happened there forty years ago.

gay rights movement is a little bar on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. That volatile night in late June of 1969 when things got rowdy at the Stonewall Inn has gone down in history as an event that changed the course of gay lives forever. It’s amazing to think that a crowd of scrappy young men and fed-up drag queens gathered their courage to fight back against the police in a raid, kicking off several nights of civil unrest and riots. The modern location of the Stonewall Inn is actually a U.S. National Historic Landmark. What’s more, there is still a Stonewall Inn at that same location at 53 Christopher Street, right on Sheridan Square. You can visit, have a drink, and pay homage to the people that started a revolution. The venue itself has changed hands many times through the years and has never quite managed to live up to its pedigree. Today, the club nights there tend to be a bit wonky and the crowd veers toward a random mix of tourists, city kids, and bridge-and-tunnel gays. But if today’s Stonewall Inn isn’t the coolest place in the City, that’s beside the point; what matters is what happened there forty years ago.

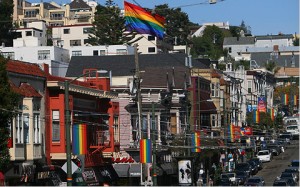

Castro Street, San Francisco. Possibly the most iconic address in Gaydom (its only rival is New York’s Christopher Street), San Francisco’s Castro Street has been a mecca for free-spirited gay  people since the 1970’s (arguably even earlier). If New York is intense and argumentative, the Castro is pure California: a neighborhood of breezy hopefulness. It’s where hippie met camp and clones met leather queens in decades past, where new combinations have continued to emerge to produce a limitless sense of self. This was the stomping ground of Harvey Milk, the Cockettes, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and so many more. It’s where sailors found themselves after World War II and realized that they never needed to go home again. The most famous landmark on the street is the Castro Theater, with its instantly recognizable marquee and, inside, its blissfully old-school organ. Today, the district is full of gay bars, eateries, and shops where one can buy gay merchandise, including completely non-ironic rainbow flags.

people since the 1970’s (arguably even earlier). If New York is intense and argumentative, the Castro is pure California: a neighborhood of breezy hopefulness. It’s where hippie met camp and clones met leather queens in decades past, where new combinations have continued to emerge to produce a limitless sense of self. This was the stomping ground of Harvey Milk, the Cockettes, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and so many more. It’s where sailors found themselves after World War II and realized that they never needed to go home again. The most famous landmark on the street is the Castro Theater, with its instantly recognizable marquee and, inside, its blissfully old-school organ. Today, the district is full of gay bars, eateries, and shops where one can buy gay merchandise, including completely non-ironic rainbow flags.

Hart, Michigan. Since 1976, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival has proven to be a female-only haven of art and expression: a rare environment where women can feel truly at ease in their surroundings (while living in tents!). The annual event takes place on a 650-acre expanse outside of Hart, a town of some 2,000 people, located in the western part of the state near Lake Michigan. An offshoot of the feminist separatist movement of the 70’s, it was a place, as After Ellen’s Malinda Lo has written, where “goddess-loving hippies from Brooklyn and pierced-and-tattooed rebels from Brooklyn” could connect along wood-chipped paths, in feminist workshops, or at performances from the likes of Alice Walker, the Indigo Girls, Tracy Chapman and Le Tigre. To be sure, there was bound to be controversy over the “women only” rule: what about small children of the male persuasion? or transpeople who started as females or those that ended that way? But the nation’s longest-running women’s event set the standard by which all subsequent crunchy lesbian gatherings would be judged.

The Colonial House Inn, Chelsea, New York. A charming bed-and-breakfast that was owned and operated by New York nightlife maven and West End Records mogul Mel Cheren from the early 1970’s until his death in 2007, the Colonial House Inn was also the place where Larry Kramer and his fellow activists found a home for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the first effective grass-roots organization for AIDS advocacy. After its founding in Kramer’s living room in late 1982, the GMHC needed a home base from which to stage its operations on behalf of gay men who were dying of this new and little-understood disease. Cheren offered the group a few rooms in the hotel for this purpose. The GMHC moved to larger digs in 1985, but the Colonial House Inn was a landmark in gay history, one in which you can still bunk in cozy style, and it sits on one of Manhattan’s prettiest blocks.

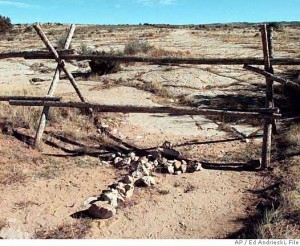

Laramie, Wyoming. Okay, this is not a travel destination as such, and it’s certainly not a place that gay people remember fondly. But due to its role in galvanizing gay activism more than ten years  ago, this small Western city—more correctly, an isolated roadside site outside of Laramie—has taken on a symbolic importance. It was here on the night of October 6, 1998, that 21-year-old Matthew Shepard was taken out into the countryside, tied to a fence, beaten, and left for dead, only to be discovered eighteen hours later, and then die in a Colorado hospital days after that. This event, and the outrage it stirred in the GLBT community, triggered a wave of hate crime legislation across the country, including the Matthew Shepard Act at the national level, which is finally moving its way through Congress. Matthew’s mother, Judy Shepard, has emerged as one of our country’s strongest and most steadfast advocates for hate crimes protection and GLBT rights in general.

ago, this small Western city—more correctly, an isolated roadside site outside of Laramie—has taken on a symbolic importance. It was here on the night of October 6, 1998, that 21-year-old Matthew Shepard was taken out into the countryside, tied to a fence, beaten, and left for dead, only to be discovered eighteen hours later, and then die in a Colorado hospital days after that. This event, and the outrage it stirred in the GLBT community, triggered a wave of hate crime legislation across the country, including the Matthew Shepard Act at the national level, which is finally moving its way through Congress. Matthew’s mother, Judy Shepard, has emerged as one of our country’s strongest and most steadfast advocates for hate crimes protection and GLBT rights in general.

Cambridge City Hall, Massachusetts. When, in the fall of 2003, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ordered that same-sex couples be allowed to marry legally throughout the  Commonwealth, it stipulated that the ruling would take effect in exactly six months. At the stroke of midnight on May 17, 2004, Cambridge City Hall opened its doors to couples wanting to tie the knot, and in doing so became the site of the first same-sex marriages in U.S. history. Affectionately known as “the People’s Republic of Cambridge,” the city of 100,000 is the home of Harvard and MIT—and is now a landmark in the history of gay and lesbian rights. Since these first same-sex marriages five years ago, an attempt by religious groups to amend the state constitution to ban same-sex marriage has been thwarted, probably for good, and a number of other states have joined the Commonwealth (Connecticut, Iowa, Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire as of this writing) in what’s starting to look like a groundswell.

Commonwealth, it stipulated that the ruling would take effect in exactly six months. At the stroke of midnight on May 17, 2004, Cambridge City Hall opened its doors to couples wanting to tie the knot, and in doing so became the site of the first same-sex marriages in U.S. history. Affectionately known as “the People’s Republic of Cambridge,” the city of 100,000 is the home of Harvard and MIT—and is now a landmark in the history of gay and lesbian rights. Since these first same-sex marriages five years ago, an attempt by religious groups to amend the state constitution to ban same-sex marriage has been thwarted, probably for good, and a number of other states have joined the Commonwealth (Connecticut, Iowa, Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire as of this writing) in what’s starting to look like a groundswell.

New Orleans. One of the first big annual events that came back after Hurricane Katrina was the annual gay party-fest known as Southern Decadence. Mere days after the 2005 storm’s wrath had forever altered the city’s physical and emotional landscape, the queer spirit of New Orleans was again beating its drum. How do you rebound from tragedy? You go back to life as usual, and in New Orleans life means throwing a party. The Big Easy’s taste for debauchery is by no means exclusive to gays, but gay folks have carved out their own niche in its hedonistic history. Here is the site of the country’s oldest, continuously operating gay bar: Café Lafitte in Exile, which you can visit any time of year. It’s on Mardi Gras that Lafitte’s becomes the center of all that gay self-disclosure and bead throwing from the balcony. It was in New Orleans that Tennessee Williams defined who he was (and where would American theatre be without Blanche Dubois?). Truman Capote and Ellen DeGeneres were both from there. There’s just something about the frisky freedom and theatrical spirit of New Orleans that leads to gaiety of all kinds.

John Polly is the editor of LOGOonline.com, a division of Logo / MTV. The text of this piece was adapted from an item on Gay365.com.