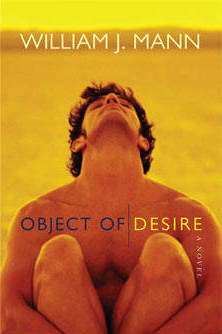

Object of Desire

Object of Desire

by William Mann

Kensington. 416 pages, $24.

NOT UNLIKE his other novels, William Mann’s latest centers on gay midlife. The protagonist, Danny Fortunato, grapples with the usual concerns of the male midlife crisis with the requisite questioning of life, love, and work. However, in Object of Desire, Mann mirrors this conflict with a haunting concern from the protagonist’s past, and the result is a mystery that leaves Fortunato seeking the answers to three questions: how did I get here, how do I move on, and what happened to my sister?

A sense of anxious questioning pervades the novel, and the quotidian nature of this very human response to change is well captured when Mann uses the metaphor of a combination lock to express his protagonist’s anxiety over attending high school. The thematic combinations that Mann usually handles in his fiction are all represented here: monogamy, geek versus chic, intergenerational relationships, sex work, the anxiety of the popular artist, and the continuing threat of hiv/aids. However, he achieves a greater resonance for his usual thematic concerns in this novel by embedding them in a three-part narrative structure.

Mann’s long fiction remains interesting for its experimentation with narrative form. Here he deploys three linear narrative threads, each of which explores a different temporal and geographic setting. Through this narrative device, the protagonist’s central conflicts in life are explored. From the suburbs of Connecticut to the gay urban center of West Hollywood and to the Palm Springs desert, the narrative trajectory alternates between the protagonist’s adolescence, young adulthood, and midlife. This narrative structure produces interesting questions about cause and effect.

However, this structure, which weaves the story of a missing sibling through the protagonist’s early adulthood and midlife period, also produces an odd contrapuntal effect at moments by placing the relatively mundane narration of life and love’s labors alongside the horror of a family tragedy without fully calibrating one to the other. The narrative pacing is also strained at moments due to excessive characterization that does not directly serve the plot. A similar strain occurs when an AIDS theme arises and reappears without its narrative purpose being as clear as it might be. However, these considerations fade when the climax is reached in the penultimate Palm Springs section, providing this memorable line: “Suddenly Frank’s face filled up every corner of my consciousness.”

Mann continues to keep an unwavering narrative eye on the domain of contemporary gay midlife and on the concessions that often haunt its long-term relationships. He’s still striving for the most efficacious structure for the presentation of his narrative concerns. Mann’s earlier novel, All American Boy, remains in my view his most fully actualized novel to date, but Object of Desire isn’t far behind.

Mark John Isola is assistant professor of English at the Wentworth Institute of Technology.