The Others

The Others

by Seba Al-Herz

Seven Stories Press

320 pages, $17.95

THE OTHERS is a trance-like excursion into contemporary Saudi Arabian life, where divisions between people inform every aspect of social behavior. Mysterious and commonplace, nationalist yet saturated with American popular culture, Saudi Arabia is a place that makes for a journey both sensuous and strange. And its exploration of lesbian sexuality places it instantly at odds with the extreme social conservatism of the Saudi regime.

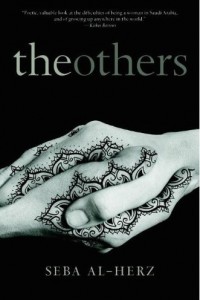

Here’s what we know before even opening the book: Seba Al-Herz is the pseudonym of a 26-year-old woman from al-Qatif in Saudi Arabia. The novel’s translator is never identified by name, and the protagonist, a young Shi’a woman in college in a largely Sunni province, is also nameless. On the book’s front cover appears an image of two hands clasping, both adorned (tattooed?) with a traditional Arabic design.

Begin reading, and you’ll find even more layers of concealment and division.

The Others takes the mixing of ancient and modern cultures in the Muslim world and spotlights the contrast between the two—as witness characters taking a break from texting when the call to prayer is sounded. “Death to America” is chanted daily over Radio Iran, and “You American, you!” is the harshest insult one can impart. Yet the narrator has watched more American films than many Americans have, eats Baskin-Robbins ice cream cones, drinks Pepsi, and mentions Eminem, The X-Files, Dale Carnegie, and The Weather Girls (“Hallelujah, it’s raining men!”). It took this reader a moment to realize that the “Leo” the narrator mentioned was Leonardo DiCaprio in the film version of The Man in the Iron Mask, and not a character from the novel.

There’s very little plot structure here to latch onto, and the namelessness of the narrator makes the novel even slipperier to pin down. The story opens with the narrator in a complex relationship with a young woman named Dai. She goes to a gathering of women and meets a woman named Dareen, with whom she connects and ends up briefly dating. The narrator has epilepsy; her seizures begin to act up and she overmedicates, which her family takes for a suicide attempt. She embarks on an Internet flirtation with a young man from Riyadh, but that relationship also dissolves. Finally she arranges a tryst with a male friend, and the book ends with them together and the narrator asking Umar not to die: “I don’t love those who die. Say that you won’t die.”

That final quotation may give some indication of the long shadows that our narrator lives under. Her family life was upended by the death of one of her brothers, which made her mother a much more nervous and clinging parent. And the city of al-Qatif itself still seems to be reeling from a sectarian uprising dating to November 1979 (Muharram 1400 by the Islamic lunar hijri calendar). With demonstrators arrested, killed, or forced to flee to Iran or elsewhere, risking arrest if they were to return, the conflict clearly informs many of the degrees of otherness imposed or assumed by the characters here.

The narrative has a rambling, earnest, kinetic quality that seems to suit a woman in her early twenties who is very confused and trying to find her way. When she’s with Dai, her mood frequently pivots from euphoria to tragedy faster than words can capture. “The minute I opened the door for her, she deposited a kiss on my cheek big enough that I felt its wetness against the cool freshness of my skin and sensed its warmth against my cold flesh. It was the kind of kiss that says, Ya Allah how much I love you! And it came from Dai, who had never actually said such a thing to me, not once.” Two pages later they are fighting, then making love. This seems at least partly to stem from the narrator’s ambivalence about her sexuality; when she’s with Dareen, this exchange takes place:

Don’t apologize for what you’re about and what you believe in, she would say. And don’t try to justify yourself to anyone! So I would ask her, Is it bad for me to say to you what I am about to say? That what I really yearn for in you is a man—a man who will never show up.

She would respond only by saying, Don’t turn your desires into a criminal offense. Don’t criminalize your needs, either.

This raises the possibility that for women who are largely kept isolated from men, sometimes right up until the point of an arranged marriage, lesbianism is less a matter of personal identity than a phase, something to tide you over until such time as a man is found, or assigned. Dai’s story of being sexually abused by a female teacher implies that her choice in the matter was taken away as a child.

The loss of an anchoring father figure is also loosely implicated as a cause.

The Others raises interesting questions but leaves them unanswered by a nameless narrator and an anonymous translator, who remain as veiled and concealed as women themselves in the Saudi Kingdom.

Heather Seggel is a freelance writer and journalist based in northern California.