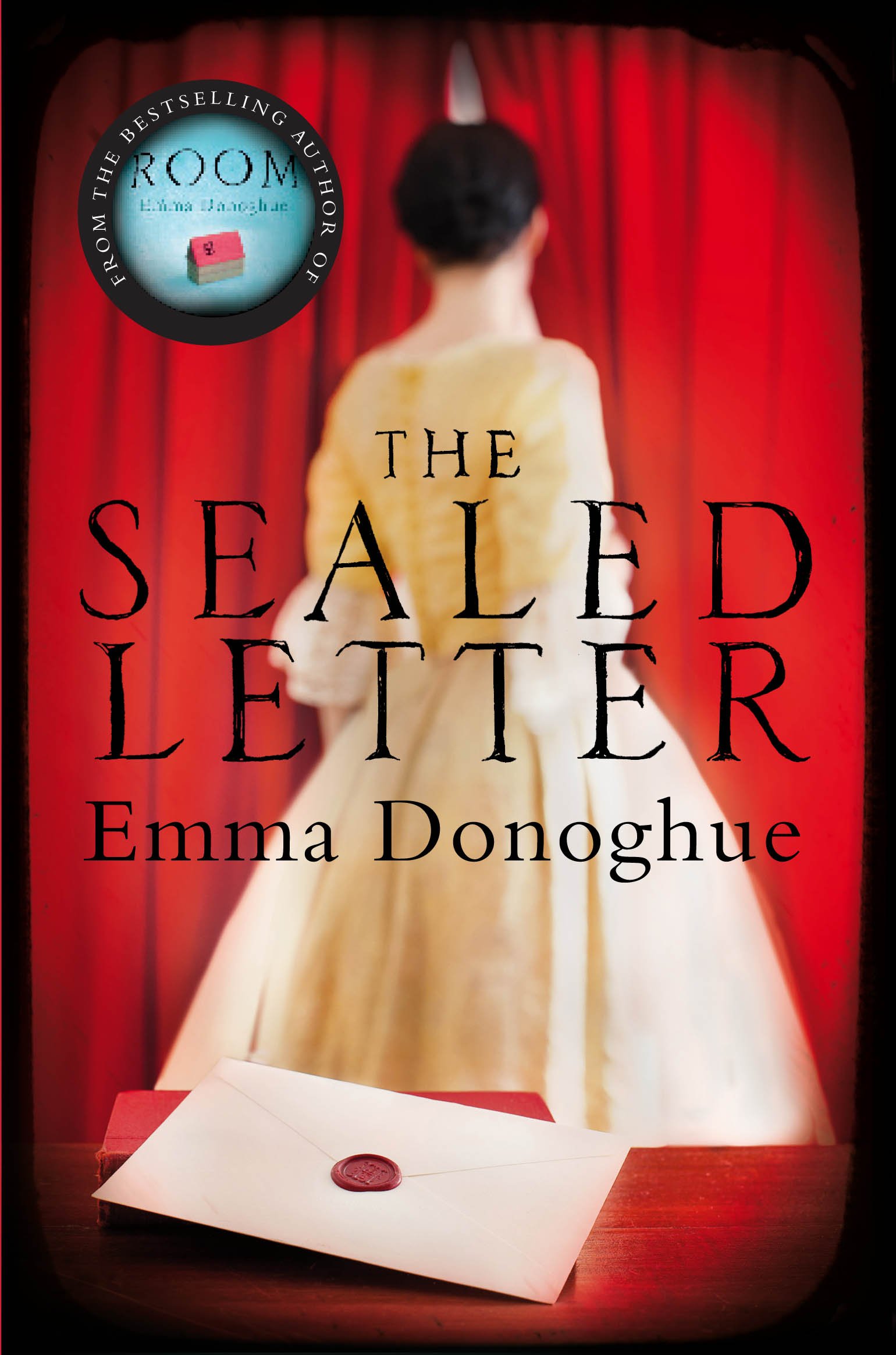

The Sealed Letter

The Sealed Letter

by Emma Donoghue

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 416 pages, $26.

EMMA DONOGHUE is an Irish-Canadian playwright, novelist, and literary historian with a gift for immersing herself in the past and presenting it for modern readers in the form of well-crafted stories. Her bestselling, award-winning novel Slammerkin (2000) captured the underworld of prostitution in 18th-century London while seducing the reader into caring about an actual teenage girl who was hanged for murder. In The Sealed Letter, Donoghue takes on the real lives behind a scandalous English divorce case of the 1860’s, a time when divorce was rare and shocking when it occurred.

Donoghue’s fiction, which is set both in historical and contemporary times, usually features primary relationships between women, some of which are explicitly lesbian. Even in the absence of clearly expressed sexual attraction, these relationships are intimate, important, life-saving, and in some cases life-destroying. This author offers us the missing ingredient: the interaction between women that was once under the radar of male-centered historical accounts.

In the opening scene of The Sealed Letter, Emily Faithfull, self-employed feminist printer, is accosted on the street by a former bosom friend, Helen Codrington, who’s back in London with her husband, an admiral in the Royal Navy, after seven years in Malta. Emily believes that Helen deliberately stopped writing to her, and the unexpected reappearance of her old friend almost shatters Emily’s habitual self-control. The drama is all in the details:

A hand lights on her [Emily’s] arm, a small, ungloved hand; the brown silk of her sleeve is caught between plump pink fingertips. She staggers, clamps her pocketbook to her ribs, but even as she’s jerking away she can’t help recognizing that hand.

“Fido?”

One syllable dipping down, the next swooping up, a familiar and jaunty music; the word skips across the years like a skimmed stone. Almost everyone calls her that now, but Helen was the first. Fido’s eyes flick up to Helen’s face: sharp cheekbones, chignon still copper. An acid lemon dress, white lace gloves scrunched in the other hand, the one that’s not gripping Fido’s sleeve. The human river has washed Fido sideways, now, into a scarlet-chested, brass-buttoned officer, who begs her pardon.

As Fido is drawn into Helen’s messy life—including her affair with the brass-buttoned officer—the women’s revived friendship is tested to its limits, and the reputations of all the major characters are tarnished. The reader learns that Fido once lived with the Codringtons and even shared a bed with Helen, usually when her husband was away. Admiral Codrington, despite his conservative values, accepted this arrangement. Since their first meeting, he has liked Fido and hoped she would have a steadying effect on his flighty wife. Even after the Admiral hires an investigator to collect evidence to use against his wife in court, Fido cannot see him as a monster, and he never completely loses his respect for her. The real villain, as Fido sees clearly, is the law that gives almost unlimited power to husbands over their wives and children.

The “sealed letter” of the title is a ploy devised by the Admiral’s lawyer to discredit his wife and her friend by innuendo. The reader knows that in the first phase of the women’s friendship, the Admiral didn’t suspect anything “unnatural” between them and probably wouldn’t have speculated about it in a letter, even to a trusted relative. But what is the truth of the relationship between Helen and Fido? In an era when sentimental friendships between women could include displays of devotion that would embarrass post-Freudian heterosexual women, the line between sexual and asexual feminine bonding could be very thin.

When the contents of the “sealed letter” are revealed, they are almost anticlimactic. The author’s use of suspense and dramatic revelation is worthy of Dickens, whose own messy marriage is mentioned in passing. The actual case on which this book is based is a tragedy, and the author gives it the operatic treatment it deserves in a big novel told from multiple viewpoints in numerous chapters with titles such as “Prima Facie,” “Feme Covert” (a reference to the law that defined every wife as a perpetual minor whose legal identity was subsumed by that of her husband), “Reasonable Suspicion,” “Engagement,” and on to “Verdict” and “Feme Sole.” For anyone with an interest in the early feminist movement, in Victorian literature, or in “women’s fiction” in the broadest sense, this book is not to be missed.

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Saskatchewan.