YOU’VE ALL SEEN THEM—that pommel in the dress of Henry VIII and others—prominent, like something to rest your hand on, dependable, serviceable: the codpiece. Where did it come from and where did it go? There are various opinions; here are some of them.

The French called the codpiece a braguette and we are told that that is one of the few words current in their language that derives directly from the Celts who ruled Europe before the Romans and Germans did. The Italians called it a sacco, the Germans a Hosenbeutel. Germanic soldiers, or the Landsknecht, clearly show codpieces around 1530. The Swiss had the Plunderhose, or devil’s pants, which were similar in appearance to the Hosenbeutel. On the island of Crete in the Mediterranean, codpieces have been found on small Minoan figures. However, this article will follow the history of the item beginning in more modern times, with the Middle Ages, glancing at its history not only in the English-speaking world but also in France and elsewhere in Europe.

In the Middle Ages (400-1400), men wore robes, with the exception of the peasants who could have a bit of drawers, long or short, of linen or leather, called braiel or breeches, attached to the waist by a belt. These leggings were tubes of animal skins held on by strips of leather and connected together at the top. The crotch was most often left almost completely open, for ease of access. One was protected from exposure by tunics, which reached at least to the knees.

One road to the creation of the codpiece was military. By the end of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), Western Europe was saturated with men-at-arms. Knights paraded on their palfreys and fought for fame, while foot soldiers attacked the enemy face-to-face for coins and booty. Foot soldiers had to be free in their movements; they could not be hampered in the tunics worn over the peasant breeches. So the tunics climbed above the buttocks, leaving at the same time the braiel/breeches (which went only from the belt to the knees) visible. Suddenly the genitals found themselves vulnerable. It was necessary to invent a shell to protect the soldier’s virility and his modesty. Warriors begin to wear a braguette/codpiece, made of iron, that jutted out below the waist from the cuirass or breastplate. French satirist François Rabelais joked in 1532 in the Third Book (Chapter 8) of The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel that the braguette/codpiece constituted “the first piece of armor among men of war.” In the foreword he comically refers to a supposed book titled On the Dignity of Codpieces.

While Edward III, the king of England from 1327-1377, was fighting the Hundred Years War, he ordered a monstrous codpiece for his armor as a way both to enhance his genitals and to intimidate the enemy. At his command the nobility fighting with him followed

suit. In France, on October 22, 1398, Charles VI (called both “Beloved” and “Mad”), addressed to the Provost of Paris a letter of permission to the hosiers of the capital to sell hose decorated with thongs that later served to affix the braguette or codpiece.

In many suits of armor, codpieces are visible. Was this for protection, for display, or to disguise disease? The codpiece in King Henry VIII’s suit of armor displayed in the Tower of London is extremely prominent. Portraits of other potentates of the time, such as those of Francis I of France and Emperor Charles V of Spain, include codpieces.

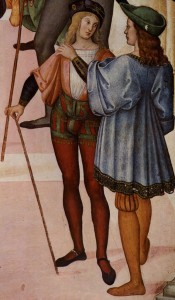

The sexually liberated Renaissance world looked to Italy for new fashion concepts and with the rise of the merchant class, fashion led to the codpieces for non-soldiers. Here, in the late 15th century, with the use of the newly popular button, garments no longer needed to be cut to fit over one’s head and new fashion leaned away from long tunics and breeches to closely fitted vests, short doublets, and hose to reveal the men’s shapely legs. People across Europe admired Henry VIII for the curves of his legs, his calves especially. Clothing for the poor remained unglamorous, of course, but for the wealthy man, changing one’s style became a way of displaying wealth, and masculinity. Men’s hems rose to mid-thigh. This was shocking, considering that their hose were still individual, one for each leg. When a man sat, or mounted a horse, one might have quite a revealing view of his private parts. All strata of society followed the new fashion, but the clergy (those who were not themselves following the fashion), as well as other guardians of public morals, were soon up in arms.

An example of their objections is found early on in the sermon of the Parson with which Chaucer concludes the 14th-century Canterbury Tales. In modern translation (original appears below):

On the other hand, to speak of the horribly immoderate scantiness of clothing, there are these short cut coats or short jackets that for their brevity, and with wicked intent, don’t cover men’s shameful members. Alas! some in their tight pants show their protruding shape, their horrible swollen members, till you’d think they had a hernia. And their buttocks look like the hind end of a she-ape at full moon. Moreover, the wretched swollen members that they show through newfangled clothing, in dividing their hose into white and red, make it look like half their shameful private parts were flayed. And if they divide their hose into other colors, such as white and black, or white and blue, or black and red and so forth, then it seems by the variance of colors that half their private parts might be corrupted by Saint Anthony’s fire, or by cancer, or by some other mischance.*

IN 1460, WE HEAR of a “kodpese like a pocket.” In addition to serving as a safety shield for the genitals, the codpiece was also a central pocket, or pockets, in which to carry around small, useful objects. They served furthermore as protective shields, keeping swords, daggers, and hard purses hanging at the belt from inadvertently banging into the gonads.

of Henry VIII, 1536/37.

Men quickly discovered that the size and prominence of their endowment could be enhanced under the guise of this new fashion. Over time, the civilian codpiece developed from a flat piece of fabric, to a pouch in which the genitals protruded, to an extremely padded pouch, (some very oddly shaped), until finally the pouch idea was abandoned, along with its supposed function, and large padded shapes of bizarre sizes appeared.

In England, codpieces progressed to a loaf shape during the reign of Henry VIII, and then developed into an elongated oval shape that poked out assertively from the folds of the puffy trunk hose early in the reign of his daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. The Spanish court, in 1550, bursting with pride over conquests in the New World, sported codpieces that proclaimed, or so it seemed, a permanently priapic male population.

Gentlemen of the Renaissance strutted elegantly in voluminous braguettes until the 1580s. During this time, common men most often wore more ample breeches or trunk-hose with less gaudy additions than their noble counterparts. For some, codpieces disguised the effects of an epidemic—possibly syphilis, brought back from the New World and known as “the great pox”—that spread through Europe in the 16th century. Among the symptoms were sores on the penis, putrid pus discharges, and painful swelling in the groin. Walking and urination became difficult. The treatment consisted of an ointment made from a mixture of animal grease with cinnabar (mercuric oxide and sulfide), which was a vivid scarlet in color and tended to stain the linen. This poultice required the application of bulky woolen wads and woven cloth bandages, distorting all of the genital area and the lower abdomen. Codpieces were painted scarlet to disguise the cinnabar ointment. The codpiece became a cover-up.

Later periods unleashed derision upon the outlandish fashion. In his Essays (Book III Chapter 5), French intellectual Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) describes this “protuberant artifice” as “a ridiculous piece, which increases natural grandeur by falsity and imposture.” By the time of Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth I of England, the fashion began to dwindle. At the end of the 16th century, the invention of side pockets dethroned the braguette. No longer having its function of storage space, it became increasingly discreet and understated until it lost its shape and prominence entirely. Eventually, a flap on the breeches replaced the codpiece for aristocratic men. For the other social classes, it took the form of a slit in the front of the breeches closed by buttons. These new baggy trousers (sometimes called slops), which not only hid the virile member but also found the opportunity in their side folds for the placement of real pockets, ruined the pretext for penile upholstery. The glory days of the codpiece were over. The braguette was obliterated and would never again find the supremacy it enjoyed in the Renaissance.

Some early poets mention codpieces, including Shakespeare. In Love’s Labour’s Lost, Berowne, who scoffs at love, has this to say:

This wimpled [blindfolded], whining purblind, wayward boy,

This senior-junior, giant-dwarf, Dan Cupid,

Regent of love-rhymes, lord of folded arms,

Th’anointed sovereign of sighs and groans,

Liege of all loiterers and malcontents,|

Dread prince of plackets, king of codpieces…

Concerning the exaggerated size of codpieces, Borachio in Much Ado About Nothing notes: “The shaven Hercules in smirch’d worm-eaten tapestry, where his codpiece seems as massy as his club.” Lucio, speaking to the Duke in Measure for Measure, uses the term in a metaphorical way when criticizing an overly puritanical ruler for condemning to death a young man for having had sex with his own fiancée: “Why, what a ruthless thing is this in him, for the rebellion of a codpiece to take away the life of a man!”

As late as 1648, English poet Robert Herrick makes an amusing comment about dinner guests and the pouch-like codpiece still in use among some men: “If the servants search, they may descry, in his wide codpiece, dinner being done, two napkins cramm’d up, and a silver spoone.”

In the following century, in France, the philosophes condemned the use of the codpiece. The stiff and heavy garments of the age of Louis XIV gave way to the jerkin, or close-fitting body garment, and to trousers. At the same time, there appeared on the scene a new kind of codpiece: the flap or fly. Called a rabot, meaning flat surface, it came from the crotch and attached itself to the belt. It would remain part of the breeches of the aristocracy until the French Revolution of 1789. This rabot varied in size; it could cover half of the width of the pelvis or all of it. During the course of the century, the military came to adopt this form of braguette for their uniforms because of the protection it afforded during training or combat. The rabot type of braguette remains a feature of the sailor’s breeches today.

With the Industrial Revolution (1760-1830), men largely abandoned the symbols of masculine power and pride associated with the body per se as the focus shifted to the mastery of machines and technical knowhow. The codpiece came to be seen as ostentatious and vulgar, especially as Victorian prudery descended upon England and Europe as a whole. The late 19th century considered the codpiece a shameful part of masculine attire and did its best to render invisible that which the codpiece had exaggerated. Men’s drawers were widely available in the grand new department stores.

Peter Garland is a historian, Navy analyst, and retired high school teacher. He has written for Navy Mech magazine, Irish America magazine, Writer’s World, Bay Area Reporter, and other publications.