George Platt Lynes: The Male Nudes

George Platt Lynes: The Male Nudes

Edited by Steven Haas

Rizzoli. 256 Pages, $60.

IN THE LATE 1970’s and early 80’s in New York, exhibitions of nude male photography occasionally sprang up like daffodils, or at least that’s what it felt like to gay men seeking beautiful images of our dreams and fantasies. It was at that time that I discovered the exquisite work of George Platt Lynes (1907-1955), mostly through my friend and colleague, photographer Duane Michals. I had seen an image or two in exhibits, but Duane showed me a new book by Jack Woody of Lynes’ work, and I became a fan.

Rizzoli has now produced an exceptional volume of Lynes’ nude male photographs, made from the prints and negatives that Lynes willed to the Kinsey Institute just before his premature death from lung cancer. Although Lynes is reported to have destroyed large numbers of his negatives and prints in his declining years, he was particularly attached to his male nudes, which largely survived. To Alfred Kinsey he wrote: “As [Somerset] Maugham says, an artist has the right to be judged by his best work. Certainly the best of these nudes are my best.” The Kinsey Institute placed these negatives in cold storage, where they have remained protected over half a century.

So, it is no small event in the history of photographic art that these images have again come to light, with more than 200 never before published. It is also the first book to be produced with the full cooperation of both the Kinsey Institute and the Lynes estate, and is therefore blessed with a readily informative, 55-page biographical essay by Steven Haas, art historian, photographer, and director of the George Platt Lynes Foundation. With much information drawn from previously unavailable letters, journals, and diaries kept in family archives, as well as the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale, Haas’ detailed research reveals much about Lynes’ extraordinary and varied social life, as well as his precociously talented artistic arc.

“I’ve always done my best work when I’ve worked only for pleasure, when I’ve not been paid, when I’ve had a completely free hand, when I’ve had a model who excited

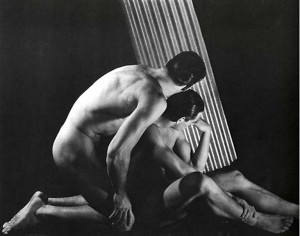

me in one way or another.” Beginning with this perfectly chosen quote from a 1948 letter to friend and former lover, Monroe Wheeler, Lynes strikes a vividly Wildean pose in assessing his creative process. His passion for looking at beautiful young men, and seeing and capturing their various human expressions and conditions, was his purpose, despite the legal dangers of the times. To make money, and to add to his glittering reputation, he took portraits of the rich and famous, did fashion shoots for major magazines, and made exquisite images of dancers in the New York City Ballet.

me in one way or another.” Beginning with this perfectly chosen quote from a 1948 letter to friend and former lover, Monroe Wheeler, Lynes strikes a vividly Wildean pose in assessing his creative process. His passion for looking at beautiful young men, and seeing and capturing their various human expressions and conditions, was his purpose, despite the legal dangers of the times. To make money, and to add to his glittering reputation, he took portraits of the rich and famous, did fashion shoots for major magazines, and made exquisite images of dancers in the New York City Ballet.

The book opens with a double-page, somewhat grainy spread depicting a naked Lynes standing in the woods, poised to photograph a naked and rec

lining Monroe Wheeler, who’s lying on a diving board above a stream. The next page shows a full-bleed image of what Lynes saw through his viewfinder.

The foreword by Lynes’ nephew, who states he was eighteen when his uncle died, is decidedly touching, revealing how warmly the older man was regarded by his family, despite being gay and often requiring their financial help to offset his reckless spending. Haas reveals that by age twenty, Lynes was bemoaning to his church rector his absence from Monroe Wheeler, with whom he had fallen in love while on a recent visit to Europe. Lynes’ father must have suspected his son’s homosexuality, states younger brother Russell Lynes, adding: “In recent years I have often been asked, ‘When did George come out of the closet?’ … He never did. He was never in it.”

Haas doesn’t shy away from discussing Lynes’ very active sex life, quoting several sources who shared such information within a close-knit group. Lynes would often send his photos of male nudes to friends for their eyes only, until a few were published in the early 1950’s in the Swiss homophile magazine, Der Kreis (The Circle). His models were often shared within this coterie, anticipating the behavior of the freewheeling urban 70’s and early 80’s. Friends with benefits, fuck buddies, group marriages, ménage à whatever—gay men who traveled in sophisticated cosmopolitan circles seemed to enjoy a rich sex life in the years before Stonewall, as long as they were cautious of the legal proscriptions.

Allen Ellenzweig’s elegantly written afterword further places Lynes in the broader historical context of homoerotic photography, referring to the male nudes as the photographer’s “private Utopia.” In addition, he cites important æsthetic predecessors, as well as subsequently famous followers whose works illustrate the depth and continuity of this artistic tradition.

The main attraction of this book, however, is the splendid photography, which embraces a glorious array of richly contrasted black-and-white images whose subjects are caressed in descriptive light to define their masculine, sculptural forms from every imaginable angle. These subjects include models, dancers, actors, friends, boyfriends du jour, and others. From this collection one can easily trace Lynes’ influence not only on Robert Mapplethorpe, Herb Ritts, Bruce Weber, and David Vance, but also on a host of younger photographers, such as Thomas Synnamon, Paul Reitz, Hans Fahrmeyer, Rick Day, Joseph Smileuske, and Henning von Berg. George Platt Lynes is a worthy tribute to a master artist, whetting one’s whistle for a full-scale—and juicy—biography.

David B. Boyce is curatorial consultant at the New Bedford Art Museum. He’s also a freelance arts writer.