Beat Atlas: A State by State Guide

Beat Atlas: A State by State Guide

to the Beat Generation in America

by Bill Morgan

City Lights Books. 240 pages, $15.95

Beat scholar Bill Morgan is the author of two literary walking tours, The Beat Generation in New York (2001) and The Beat Generation in San Francisco (2003). Some of the material in Beat Atlas seems to come from his The Typewriter is Holy: The Complete, Uncensored History of the Beat Generation (2010), which inexplicably omits any mention of Beat poet Harold Norse. Allen Ginsberg had, said Morgan, accomplished his plan to read “Howl” in every state, and that alone would have justified this book, which is arranged by geographic region and covers all fifty states. There are entries for major and minor Beat writers, their admirers, publishers, hangers-on, lovers, the libraries housing Beat collections, the libraries frequented by Beats, the jails in which they were occasionally housed, and the homes of artists who influenced their style. Such was the case with one of the entries for Detroit, home of jazz musician Slim Gaillard, whose scat singing influenced Kerouac’s writing style. Provincetown appears, too, as the place where Allen Ginsberg had his first heterosexual affair, with his friend Helen Parker at her summer house. The affair, though brief, was documented in a letter to Kerouac. There are enough Boston and Cambridge Beat connections to merit another walking tour title: just for starters, there were Harvard graduates William Burroughs, Alan Ansen (Auden’s secretary and Naked Lunch’s editor), John Weiners, Frank O’Hara, and Poets’ Theatre founder Violet “Bunny” Lang. Beat Atlas has a fairly complete index, but the lack of any maps is regrettable. The determined reader could, of course, consult an on-line map site.

Martha E. Stone

The Fish Child

The Fish Child

by Lucia Puenzo

David William Foster, translator

Texas Tech Univ. Press. 161 pages, $26.95

The intense love between two young women is at the heart of this intriguing novel from Argentina. Lala, the teenage daughter of a prominent judge in Buenos Aires, is passionately in love with Guayi, the Paraguayan maid working for her family. Hoping to escape her dysfunctional family, including a father who appears to be having an affair with Guayi, Lala finances a trip to Guayi’s hometown near the border, where they will live comfortably. Upon arriving, the novel takes a slight turn into magical realism, with brief sightings of a young boy living in the lake, said to guide drowning victims to the bottom. Lala learns some of her lover’s tragic past stemming from a relationship with a famous soap-opera star, which caused her to flee her town for Buenos Aires. Later, Lala must return to the city and her family to rescue Guayi, who has been imprisoned for a crime Lala in fact committed. Exploring the poorer sections of the city, Lala finds allies to help her free Guayi, finally discovering the sad truth behind the mystery of the fish boy. While it’s a pleasure to read a novel where lesbian relationships are accepted as a matter of course, The Fish Child is disappointing in other respects. The title character is really a minor character, mentioned several times but only seen once. And learning the truth behind him turns his story into a mundane one. In addition, the book is narrated by Lala’s dog, which seems unnecessary and a little hokey. Still, David William Foster does a wonderful job of translating, allowing Guayi to retain a few phrases of Paraguayan, emphasizing how foreign she is even within this exotic location. And the novel fiercely demonstrates the sharp divide between rich and poor in Argentine society.

Charles Green

I Was Born This Way: How About You?

I Was Born This Way: How About You?

by Doug Green

AuthorHouse. 171 pages, $16.26

This brief memoir recounts the author’s struggle to live authentically and find love in a world often unforgiving of difference. Born in Vermont in 1939, Doug Green was acutely aware from a young age that he was different from most other children. Having little interest or talent in traditionally masculine activities such as sports or fishing, he often felt like a disappointment to his father, preferring picking flowers and reading books. While his parents clearly loved him, they lived at a time when homosexual feelings in boys were thought to result from “sissy” habits that could be controlled and corrected. Suffering from poor grades and anguish over his sexuality, he was sent by his parents to a military prep school, where he seemed to adapt to the strict discipline, although he still struggled over his feelings for men. Yearning for freedom, he hitchhiked to New York, only to be raped and left sick by the truck driver who picked him up. Later attending a small, progressive college, he found a community where artistic pursuits were embraced and where differences, whether racial, sexual, or cultural, were celebrated and explored. After an adventure teaching French in a remote community in Canada, he moved to New York, met his partner of 36 years, and raised two children while working with people with disabilities. While Green’s story of searching for love and acceptance is remarkable and touching, at times it feels disjointed and stitched together. Still, I Was Born This Way serves as a reminder of just how difficult it was growing up gay in the 1940’s and 50’s.

Charles Green

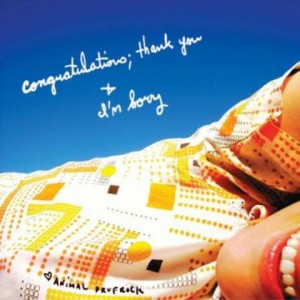

“congratulations; thank you + i’m sorry”

“congratulations; thank you + i’m sorry”

by Animal Prufrock

Righteous Babe Records

Produced by Ani Difranco

Who or what is Animal Prufrock? This nom de musique must be some kind of queer joke on T. S. Eliot’s neurotic persona of 1915, with “animal” added for ironic contrast. At just under 35 minutes, the female singer’s debut album is a strange breed. Recorded in New Orleans and San Francisco, its sound exists somewhere between the gay cabaret downtown and sing-along hour in an afterschool music program. Aptly named, Animal Prufrock is the protégée of veteran singer Ani Difranco, who remains one of the most visceral performers in the folk-rock scene. Difranco, a Buffalo native and founder of her own label called Righteous Babe Records, is known for mining her psyche, and her bisexuality, for inspiration. Her own considerable output isn’t comprised of songs so much as outcries, and in this respect Prufrock is a faithful follower. On “La Mia Ragazza,” Prufrock alternates between a whisper—”My girlfriend is a vegan/ She don’t eat animal”—and a squeal so shrill it could startle a deaf dog. On “Love me Love me,” she warbles her charming plea over a fairly simple string of piano chords, while the more restrained “I like you” will have feet tapping in no time. Then again, “Emotional Boner” and “Cosmic Tranny” are songs for grown-ups: “You give me an emotional boner/ It’s in my heart dear, that bleeding muscle.” Prufrock doesn’t identify as either male or female, gay or straight, and indeed she makes music that deconstructs the categories of genre and gender. This album belongs to a musical Zeitgeist known as “queercore,” a punk-based scene originating in the 1990’s. Animal Prufrock has made a fine record, one whose sound is both playful and unpolished. But it also sounds a bit like an artist still in search of her voice.

Colin Carman