THIS OCTOBER marked the fiftieth anniversary of artist Don Bachardy’s one-man debut at the prestigious Redfern Gallery in London in 1961. It was in the cramped, closely hung confines of a basement gallery that the 27-year-old Bachardy exhibited much of the work he had completed that year, notably a series of celebrity portraits. “All that year,” he told me during a recent conversation, “I drew everybody I met: John Gielgud, E. M. Forster, Gladys Cooper, Deborah Kerr. By the end of the summer, I had quite a collection of portraits.”

Bachardy once called his period of drawing famous people his “boot camp,” providing the training—and exposure—that he needed to establish himself as a serious artist and get noticed. And noticed he got: “It was a major event. A tremendous success. Everybody came to my party.” The list of attendees reads like a who’s who of gay London society at the time: Forster, J. R. Ackerley, Francis Bacon, W. H. Auden, as well as the aging Somerset Maugham. “He almost never went out to social occasions at that time of his life,” Bachardy reminisced. “But because he was fond of Chris, he made an appearance.”

“Chris” is of course Christopher Isherwood. Perhaps best known as the author of The Berlin Stories (1945) and A Single Man (1964), he was Bachardy’s lover for over thirty years. In his diary entry for October 2, 1961, Isherwood wrote that the Redfern opening was “a truly marvelous event.” The more sought-after upstairs galleries, where two other shows were concurrently taking place, were “practically deserted,” he gloated. “And our downstairs room, which was quite obviously the worst of the three positions … was crammed to halfway up the stairs.”

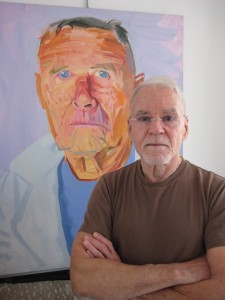

On a recent visit to Bachardy’s painting studio—the converted garage of his home in Santa Monica—I was immediately struck by two things: the dazzling Southern California light glinting off the Pacific and a large oil painting of Isherwood that hangs on one of the walls. “The light is just wonderful,” Bachardy agreed as he showed me around the studio. Now approaching his late seventies, he maintains a trim, athletic body. “Around six o’clock in the evening, the whole place is lit up brilliantly.” He paused to pour us black coffee from a thermos. “It’s a perfect studio for me. I’ve never tired of the view and I’ve lived here nearly fifty years.”

I asked about the impressive painting of Isherwood. “It’s my last canvas of Chris. I did it in preparation for the Jerry Brown sittings. I hadn’t worked on canvas in a couple of years and I felt rusty. It was one of those paintings in which I couldn’t put a brush wrong. It painted itself.”

Dozens more of Bachardy’s bold, colorful portraits were hanging on the studio walls. They are a small, representative sample of the thousands of paintings and drawings he has done over his long career. An easel sat near the day bed. Pots of brushes and tubes of paint occupied the counter near a small sink. The room was tidy and clean, awash with natural light. Bachardy noted with pleasure that our visit was taking place on the first day of spring. Pleasure—the artist’s delight in seeing things freshly at every moment and in every season—infused his entire manner during our two-hour visit.

From the time he was a child, Bachardy, who was born in 1934, loved to draw. “Always pictures of people, invented from my imagination or inspired by magazine pictures.” He attributed this fascination with people, especially celebrities, to his early love of the movies, but admitted that he’d never stepped into an art museum until he met Isherwood. His parents thought his flair for drawing “charming,” though they never gave him encouragement. “In fact, active discouragement from my father, who was determined that I’d get a job with security. He simply didn’t understand me, or want to. We grew apart by the time I was seven or eight.”

Bachardy’s older brother Ted was also gay. “Ted was a great beauty and had a large selection of beaux to choose from. He found them on the beach. Right down there.” He motioned out the window, down to Will Rogers State Beach along the Pacific Coast Highway. “It’s always had a queer section. We used to take the streetcar. It took about two hours to get to Santa Monica. I hadn’t come out to Ted yet. I was just tagging along. Ted used to say to his friends: ‘Keep it down; my little brother doesn’t know anything.’ Well, his little brother knew a lot more than he thought.”

It was on that beach, circa 1951, where the two Bachardy boys met Isherwood, who had immigrated to the United States from his native England over a decade earlier. “Chris was a great charmer,” Bachardy confided. At first, it was the older Bachary brother who succumbed to the distinguished writer’s allure. He and Isherwood began a casual sexual relationship. Over a year later, on Valentine’s Day, 1953, the younger brother followed suit. “We’d spent the whole day on the beach with Ted,” Bachardy recalled. “Ted was driving us back to Chris’s place. When Chris got out, I suddenly said to Ted, ‘I’m going to spend the night with Chris.’ That rather surprised him; I don’t think he particularly liked it, but I knew he had a date that same evening. Anyway, I was eighteen; I was officially able to make decisions for myself, and I did.”

A few weeks later, Ted suffered a nervous breakdown, the second of many over the years, and was institutionalized. “Ted was the key person in my life, and suddenly he wasn’t there for me anymore. I felt abandoned. Chris started inviting me to the ballet, the theater. We found we enjoyed each other’s company.”

By early March, Isherwood could write in his diary, “I feel a special kind of love for Don. I suppose I’m just a frustrated father. But this feeling exists at a very deep level, beneath names for things or their appearances.”

After several months, Bachardy proposed that they live together. “He was just fun to be with. I thought it was a declaration of friendship.” But the innocent suggestion rattled Isherwood. “Chris became grave and serious, because it sounded like a proposal to him. He was more interested in me as a sex partner, and here was this declaration from me that he read as a declaration of love. It surprised Chris into thinking in terms of a more serious relationship. I said to myself, Well, that hadn’t really occurred to me, but if that’s what he’d like, why not?”

That Christmas, Isherwood took Bachardy to New York for the first time. “He was 48, and I was eighteen. I looked twelve. He was very happy to show me off to all his friends, who said ‘Where did you find him?!’ A serious rumor went around that Chris had brought a twelve-year-old from California.” In his 1980 memoir My Guru and His Disciple, Isherwood observed, “I myself didn’t feel guilty about it, but I did feel awed by the emotional intensity of our relationship, right from its beginning; the strange sense of a fated, mutual discovery.”

And what were Bachardy’s initial feelings toward Isherwood? “I was always more comfortable with people older than myself. I loved being with him, loved being adored by him. He always knew better than anybody else how to flatter me to pieces. Chris saw in me what I couldn’t see myself and he drew it forth and that’s what I needed. He believed in me. For years he believed in me more than I believed in myself.” Did he think that he and Isherwood could have begun such an unorthodox relationship these days? “Oh, I’m so tired of that. You see, Chris and I were both very unusual people. We always agreed that, rather than an obstacle, the age difference was our lucky card. That’s what made it possible. There was none of that rivalry that so often exists between two young men setting up house together. He was always championing me, encouraging me. He made it possible for me to become an artist. I would never have had the confidence in myself without him.”

Isherwood became Bachardy’s first live model. Before that, he had just copied photographs of people out of magazines. “Life drawing was a completely new experience. I put in absolutely everything I could see. It took me about an hour. I remember when I was finished, Chris stood up and came to see what I’d done. There was a very silent pause before Chris said, ‘You know I think it’s very good; it’s very like me.’ But the pause was one of shock. I did hundreds and hundreds of drawings and paintings of him over the years we were together, but I never did one as old looking as that one.” Eventually, with Isherwood’s encouragement, Bachardy enrolled at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. “Once I applied the accuracy that I had learned from copying photographs, I instantly made progress.”

Through Isherwood, Bachardy also began meeting lots of luminaries, including the Huxleys and the Stravinskys, expatriates who had, like Isherwood, settled in Southern California. “The Stravinskys became our best-loved friends. We felt our evenings with them were the evenings we looked forward to most. I was smart enough in those years to keep my mouth pretty much shut and my ears wide open. And Chris educated me. He was such a perfect example of what an artist is. He explained to me what the purpose of art is and how you give it the very best you’ve got. He always felt that the religious life and the artist’s life were parallel, that you could build one or the other on more or less the same principles.”

The education extended to Bachardy’s adoption of Isherwood’s British accent, which he retains to this day. “People thought I was the most affected creature imaginable, but I couldn’t stop it. If I was going to copy someone, what great good fortune to have it be Chris.” Among the people that Bachardy met was Isherwood’s guru, Swami Prabhavananda, founder of the Vedanta Society of Southern California. Only the swami’s high regard for Isherwood kept him from disapproving of his relationship with the young Bachardy. “It shocked the congregation: not only an open queer but one with a boyfriend who looked so young. Of course, they didn’t dare speak [of it], because swami ruled with a strong hand, and he was determined to keep Chris as his disciple.”

Isherwood, who was a life-long diary keeper, urged Bachardy to begin a journal, too. Isherwood’s diaries, meticulously edited by Katherine Bucknell, are being published by HarperCollins. I asked Bachardy if he plans to publish his own diaries one day. “Well, I do have volumes and volumes. I’m not a writer really, but anybody who is interested in Chris would be interested in this material. He was a very witty man and I quoted [many of]his remarks. My diaries are full of laughs.” Bucknell is also working on a volume of Isherwood and Bachardy’s letters to each other. “We weren’t separated often, but when we were we wrote almost daily.”

As deeply as the two men loved each other, theirs was not a sexually exclusive relationship. Bachardy had affairs with other men. “I insisted on it. How could he deny me? I knew all about his youthful adventures, all of the guys he’d slept with. He knew he had to give me my freedom. I took it just as a matter of principle. I was testing him all the time, just to see how true he was to his word. He never, ever made me think, ‘Well, you’re not as true as I thought you were or as you’d presented yourself.’”

As the years went on, Bachardy honed his skills, especially as a pencil portraitist. Books like October (Twelvetrees Press, 1981), One Hundred Drawings (Twelvetrees Press, 1983), and Stars in my Eyes (Wisconsin, 2000) attest to both his exquisite technique and his ongoing fascination with celebrities. He is candid about the demands of working with celebrities. Painting the official gubernatorial portrait of California’s Jerry Brown was, he recalled, particularly frustrating. “He was one of the most difficult sitters. He was terrified that I was going to make an ass of him, that I’d do something that would make him look ridiculous. He would sit in the same chair for hours, but he’d be miles away. He’d be in his head. When he was with me, he was suspicious of me. If you look at the portrait, his suspicion is palpable.”

Celebrity sitter or not, Bachardy describes the experience of drawing someone as “being alone with another person while looking intently at him or her. … It’s getting out of my own skin. I’m so into the experience of looking and identifying that I’m not thinking about myself. And you know, that’s as close to bliss as I think I’ve gotten.” He still adheres to a practice he adopted early on, of completing each work in a single sitting. “The departure of my sitter is like the breaking of a spell. I never alter any detail of the work I’ve done once the sitting has ended. Even in the space of one sitting, my sitter goes through an extraordinary range of moods. I can often barely keep up. My best work is really like a time exposure in which I’m getting a little bit of each mood into the picture I’m doing.”

Isherwood died at home on January 4, 1986, at the age of 81. “In the first months we knew each other, I remember his saying to me that it wasn’t death that he was afraid of; it was dying. His idea of the worst dying experience was to do it in a hospital. Naturally, we assumed that he would die before I did. We often spoke about it. We’d joke about it. I’d say, ‘You’re going to live just long enough until I’ve lost my looks completely and I won’t be able to find anybody else.’ ‘Oh, no,’ he’d say, ‘you’ll find somebody.’ And I’d say, ‘Yeah, it’s easy for you to say.’ I knew that when he got sick, I’d do my best to keep him at home, and I did.”

In the months that preceded his lover’s death, Bachardy gave up all other drawing commitments and drew only Isherwood, sometimes as many as eleven or twelve drawings a day. “In those last months, Chris changed drastically. He was often in states I’d never seen him in. If I had just stood around wringing my hands, watching him slowly dying, it would have been agonizing. But I gave myself this extraordinary challenge to record almost every day what was going on. He was in great discomfort. It was really hard on him. But he was responsible for my being an artist, and this was the greatest tribute I could give him.” For these drawings, Bachardy adopted a different style, one that “engaged the whole arm as much as the practiced fingers,” as John Russell put it in the introduction to Christopher Isherwood: Last Drawings (1991).

“Chris had always been the perfect sitter,” Bachardy noted. “But in those last months, he was failing, so his concentration wasn’t nearly as good. In the last weeks, he was in bed—awful artificial light, worst working conditions. I couldn’t have my way any longer. I was just making do with whatever circumstances were happening. It got me through.”

The drawing continued even after Isherwood died: for several hours Bachardy drew the corpse. “It was a spontaneous decision, though it must have been in the back of my mind.” It took Bachardy several months before he could review those final drawings. When he finally did, he “marveled that I could record in the drawings what I saw. It’s the work I’m proudest of. I’ve not sold one of them. I’ve never let any of them go.”

In the more than twenty years since Isherwood’s death, Bachardy has continued a vigorous schedule of drawing and painting. In the late 1980s, he created a series of portraits of early gay rights leaders for the Mariposa Education and Research Foundation. A few years ago, the Huntington Library mounted an exhibition of his portraits, an unusual move for the institution, which rarely shows the work of living artists. And while he no longer pursues actors to pose for him, Angelina Jolie, during her first pregnancy, commissioned several portraits of herself, naked, in each of her three trimesters.

The Jolie commission notwithstanding, today most of Bachardy’s nudes are of men. “They don’t have to be young,” he hastened to remark. “I very much like doing nudes of middle-aged men and old men. I like exploring my homosexuality in every corner. Those who really engage with me and go with the experience are as interested in it as I am. Those are the great sitters. Some say it’s been a profound experience. That’s what I hope for—that they’ll get as much out of it as I do.”

Now approaching 78, Bachardy is “still doing my sittings. And still finding it as difficult to do as anything I can imagine. And that makes me think I must be doing something right. The toughest thing for me is to do a sitting with somebody I’ve known maybe ten years, fifteen years, because I can’t help having a preconceived idea of what they look like. And when I sit down and look at them like I only look at people when I’m working, I realize that all my preconceptions are completely wrong. It’s like having a mini-nervous breakdown the first few minutes: do I draw what I think ought to be there or do I draw what I’m seeing for the first time? Of course, that’s what I draw. It’s wonderful not to have any preconception and just be as objective as I can.”

Philip Gambone’s most recent book is Travels in a Gay Nation: Portraits of LGBTQ Americans (Living Out: Gay and Lesbian Autobiog) (Wisconsin, 2010).