DURING THE 1950’s, influences from pop culture, countercultures, and consumer marketing initiated a significant shift in the ideas and ideals of postwar masculinity. The conformist “man in the gray flannel suit” found himself suddenly confronted with new ideas about male eroticism and exhibitionism as reflected in fashion choices. Young men of the 1950’s began to adopt the body-conscious Italian cut suit, also called the “Continental look,” made with a fitted coat and slim trousers that highlighted the youthful physique—natural shoulders, narrow waistline, slim hips, and shapely thighs. In Jailhouse Rock (1957), Elvis “the Pelvis” Presley exhibited sexually charged dance moves to rock-and-roll music that celebrated the eroticism of the young male figure in tight jeans and fitted sports shirts with the short sleeves rolled above his biceps. James Dean likewise helped make tight-fitting jeans a look of masculine eroticism in Rebel without a Cause (1955). Marlon Brando turned the ubiquitous white cotton T-shirt into a fetish when he ripped one from his muscular torso in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). In From Here to Eternity (1953), Burt Lancaster made the formfitting swim brief a component of sexual foreplay with Deborah Kerr on the beach.

Marketers of men’s underwear and swimwear added to the emerging trends of the sexualized male with new styles specifically designed for erotic exhibitionism. Prior to 1950, men’s swimwear always concealed the navel, even though rubberized Lastex yarns shaped and articulated the genital bulge below. In the early 1950’s, though, styles of men’s swimwear began to reveal more skin. Some inched below the navel, peek-a-boo cutaways bared the hips, and the male bikini made its first appearance on American beaches. New miracle fabrics applied to swimwear, particularly filmy elasticized nylon, molded to the genitals and buttocks even more fluidly than Lastex and became virtually transparent when wet. In underwear styling, the nylon knit bikini Skants, with a mere one inch of fabric at the hips and a waistband that plunged to just above the pubic hairline, was launched by Jockey in 1959.

As radical as these menswear fashions seemed at the time, they were but a prelude to the sexualized fashions of the Peacock Revolution in the 1960’s. The youthquake generation overthrew the conventions of male dress and masculinity by growing their hair long and adopting gender-bending forms of dress. The sculpted constructions of suits reflected the new body consciousness. Shirts made of voile, mesh, lace, and other sheer fabrics displayed lean torsos, navels, and nipples. Skintight hip-hugger pants emphasized the crotch, buttocks, and thighs. Underwear became ever briefer to fit beneath lowered waistbands of trousers and to prevent bunching beneath snug inseams. On the beach, swimwear made of the new Lycra blend knits and cut with hip-hugger or brief styling provided for nearly nude public exhibitionism. “Man’s natural tendency to peacock it has led to what

scientists call an increase in exhibitionism,” asserted Men’s Wear in 1969 (July 11 issue). “This is evidenced by the styles and garments that unabashedly emphasize the male form. … Much of what people wear today is meant to expose the body while covering it. This exhibitionism is also reflected in the increase in male nudity … and coupled with this an increase in garments with the nude look.”Marketers of the newly eroticized styles of underwear and swimwear had to walk a fine line because of the hysterical criticism from traditionalists that the new sexual permissiveness of the era, and especially the radical changes in men’s fashions, were contributing to an “alarming increase in homosexuality.” “Fashion consciousness that has been the domain of the female and the fag is sweeping into the male population,” complained Men’s Wear. Certainly such pronouncements were not new in the 1960’s. As early as the late 1930’s, Esquire objected to the influence of the “fairy” in the fashion industry—the “male designer who is a pansy” and the “lily lads” who “maliciously make saps out of the slaves to fashion” (April 1938 issue). America’s long history of puritanism and homophobia was all the more reason for particular vigilance by mass market advertisers. Hence, even as makers of underwear and swimwear produced a steady stream of products designed and branded with a specific erotic intent, they struggled to achieve marketing images and messages that denied homosexual appeal. Only the public’s naïveté about the existence of homosexuals allowed marketers to present erotic male clothing to the masses through formulas that combined subtle ad copy with vaguely homoerotic images.

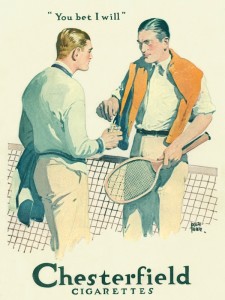

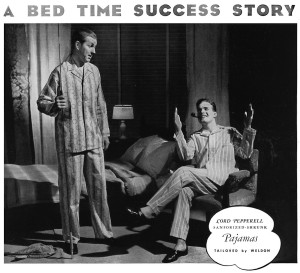

Going back to the illustrations and photos of the interwar years, we may wonder how marketers could so carefully guard against erotic displays of underwear and swimwear models, meticulously airbrushing bulges out of photos, and still be oblivious to such homoerotic imagery as the “buddy” scenarios (today’s “bromance”) in advertising. In the examples shown here from the 1920’s and 30’s, the homoeroticism of the fully dressed men seems more apparent than almost anything depicted in underwear and swimwear ads of the same time (Figure 1). The two tennis players in the Chesterfield ad are sharing more than a cigarette brand, judging by their intense gaze into each other’s eyes underscored by the suggestive caption, “You bet I will.” And in “A bed time success story” from Weldon sleepwear (Figure 2), a double bed with two pillows seems the only logical destination for the two men in their pajamas. Likewise in the London-Kenton ad (Figure 3), the drama between the two young men appears to be intimate, despite the grins, as the one on the bed holds up a clock, allowing the viewer to imagine him exclaiming, “Do you know what time it is?” (or “Where have you been?”). Perhaps to the marketer of the era, and presumably to the consumer, the fishing tackle props and the college dorm accoutrements safely anchor these images in the innocently homosocial rather than the homoerotic genre as we might see them today. As dress researcher Paul Jobling suggests in his 2005 book Man Appeal: Advertising, Modernism, and Menswear: “the camp gestures and poses portrayed in [these ads]also nod in the direction of queer desire, and trade on the irony that those in the know will recognise such codes while those on the outside will remain oblivious to them.” Then, too, “a number of artists and admen of the day were homosexual, so it would not be unexpected for their affectional desires to have seeped into their ads.”

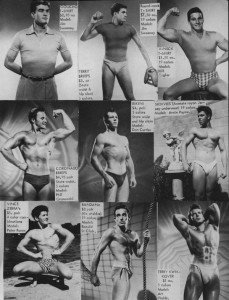

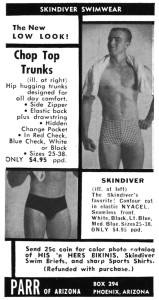

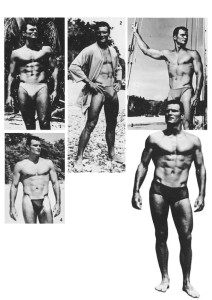

Despite the relentless oppression of homosexuals by the medical profession and the government, particularly during the witch-hunting McCarthy era, marketers of underwear and swimwear began to target gay consumers more openly and directly in the 1950’s. A precursor to the thong based on the male model’s “posing strap” was privately produced by AMG (Athletic Model Guild) in 1951 and advertised in gay-targeted publications like Physique Pictorial. Response from the gay market was sufficient for AMG to expand its line of sexy clothing to include bikini- and brief-cut swimwear and underwear in assorted styles and fabrics, as well as formfitting knit polos and T-shirts (Figure 4). In 1955, Ralph Parachek founded Parr of Arizona, producing red gingham bikini briefs, black leather jeans, and a variety of similarly provocative men’s items. The type of “frankly masculine” clothing from Parr was “as influential on its side of the fence as Fredericks of Hollywood is on its [side],” declared Gentlemen’s Quarterly (in the Summer 1971 issue). From London came similarly sexy fare, including bikini underwear and swimwear designed by Vince Green and imported by Macy’s.

To expand business beyond their local shops, both Parachek and Green produced mail order catalogs featuring young physique models and bodybuilders—a significant departure from typical menswear catalogs. “For a certain section of society, notably non-effeminate homosexual men, there swear retailers like Parr of Arizona, Ah Men, and The Village Squire began to advertise extensively—using the same types of muscle boys as models—in national men’s style magazines such as Esquire and GQ (Figures 5–7). To what degree this barrage of ads depicting the beefcake male wearing overtly sexy clothing influenced mainstream menswear of the 1950’s and 60’s is unclear. However, by the end of the 50’s Jockey had launched its Skants bikini underwear for men, and fashion editorials had already reported on the first men’s bikini swimsuits seen on American beaches. Moreover, the regular placement of these types of ads in mass market magazines suggested to a broader socioeconomic spectrum of readers that a muscular male æsthetic, and with it a new exhibitionism upheld by ever briefer styles of underwear and swimwear, was more pervasive than merely on muscle beaches, in inner-city gyms, or in gay-oriented physique magazines.

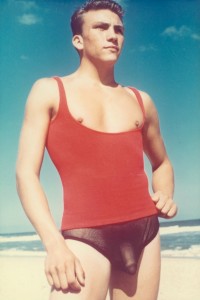

Throughout the 1960’s, the gay market continued to push the boundaries of sexualized clothing and marketing presentation. Some styles of men’s underwear and swimwear offered by Ah Men and Parr of Arizona became fetishistic in cut and materials. String bikinis were worn on the public beaches of Fire Island a decade before the “rio” style of swimwear was imported by American distributors. The sheerest of silk, nylon tricot, and other transparent materials were fashioned into various cuts of boxers and briefs designed solely for erotic display. Tank tops were cut with plunging scoop necklines to accentuate muscular pecs and to expose the nipples (Figures 8 and 9). Photos of these items worn by athletic young men in catalogs from Ah Men and Parr of Arizona rivaled anything published in the gay-targeted physique magazines of the time. Even the phraseology in the ad copy, such as the double entendre header, “Bob Gentry cruises the islands,” in the Ah Men ad in Figure 7, is directed at gay men who understood the term “cruise” differently from straight men.

Despite the expanding representation of these images in men’s publications, the majority of underwear and swimwear marketers of the Peacock Revolution era remained cautious about the types of images used in ads, catalogs, and product packaging. Although mass merchandisers like Sears, J.C. Penney, Spiegel, and Montgomery Ward stocked the new bikini forms of men’s underwear and swimwear as early as 1961, they continued the old tradition of cartoonish artwork or airbrushed photos of male models into the early 1970’s. But as the decade wore on, the appearance of the trim, muscular male continued to gain mainstream prominence. This development was bolstered by four important influences.

First, as the youth-obsessed baby boomers began to turn thirty, thousands of men joined fitness clubs and took up physical training to recapture or sustain the trim, athletic bodies of their younger years. Many men went beyond the goal of merely slimming down and pursued vigorous exercise regimens to reshape their bodies into the muscular ideal they had so often seen in underwear and swimwear ads. In 1977, the bodybuilding documentary Pumping Iron, which made Arnold Schwarzenegger famous, “took the sport out of the gym and made it big business,” reported Esquire (June 1986). Schwarzenegger “all but erased the deep-seated image most Americans harbored of the body builder as a stupid, coordinatively helpless narcissist with suspect sexual preferences.” In 1980, the movie American Gigolo provided a vehicle for Richard Gere’s character to obsess about his muscles, which he proudly exhibited, fully nude, for costar Lauren Hutton.

Second was the emergence of the “gay clones.” As the gay and lesbian rights movement gained momentum in the 1970’s, gay men became more open and conspicuous in cities such as San Francisco, Miami, and New York, where large gay communities had developed. Many of this new generation strived to distance themselves from the stereotype of the effeminate male homosexual by adopting “manly attire and demeanor as a means of expressing their new sense of self, and in adopting this look they aimed to enhance their physical attractiveness and express their improved self-esteem,” according to Shaun Cole (2000). Key to this development was a cult of muscles. To maximize their attractiveness to other men, gay clones of the 1970’s—the cowboy, the biker, the lumberjack, the construction worker—spent many hours working out in gyms. In addition, the hypermasculine gay clone popularized facial hair, especially thick mustaches and the display of hairy chests beneath fitted shirts worn halfway unbuttoned—a look that was quickly adopted by straight men who were doubtless unaware of its origins.

Third was the launch of Playgirl magazine in 1973. For the first time, men were objectified purely as fantasy sex objects in a broader, mainstream market. But the men of Playgirl were not the typical Hollywood heartthrobs or stylized menswear catalog mannequins. These men were young, muscular, and proud to bare all for the camera and a broadly targeted female readership. For straight men glancing at the covers of Playgirl on the newsstand, or perhaps surreptitiously thumbing through a girlfriend’s copy, the muscular æsthetic was not only reinforced but also was colored with an explicit male exhibitionism, an erotic performance that often included new styles of underwear or swimwear.

Fourth was the disco culture with its uninhibited sexual freedom. Men and women dressed for success in daytime but for sex at night. Straight men adopted many of the gay clone’s attributes for sexual display—from baring hairy chests to wearing designer jeans with a painted-on fit over crotch- and butt-enhancing briefs. In the movie Saturday Night Fever (1977), John Travolta sleeps (and later poses, flexing his muscles before a mirror) in black bikini underwear. For the first time in movie history, men’s underwear was presented expressly as sexual attire, and millions of men took notice.

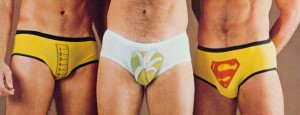

As a result of these shifts in social attitudes and pop culture influences, underwear and swimwear makers began to alter their approach to marketing in the 70’s. Almost overnight, the airbrushed photos and cartoon models vanished from advertising. Underwear advertising took the lead in presenting male exhibitionism. Narratives in ads distilled the cult of muscles, Playgirl models, and disco-era sexuality into a single message: men could now think of underwear as sexually alluring to women (and perhaps even an element of foreplay). The ever briefer, sheerer designs of men’s underwear were a barometer of the changing social mores of the Sexual Revolution. The fashion industry even began to parody itself by producing underwear with risqué screen prints over the crotch, such as an upright ruler measuring seven inches, a groping female hand, an elephant head with the trunk lifted up, red lipstick kisses, and hundreds of similar graphics (Figures 10 and 11).

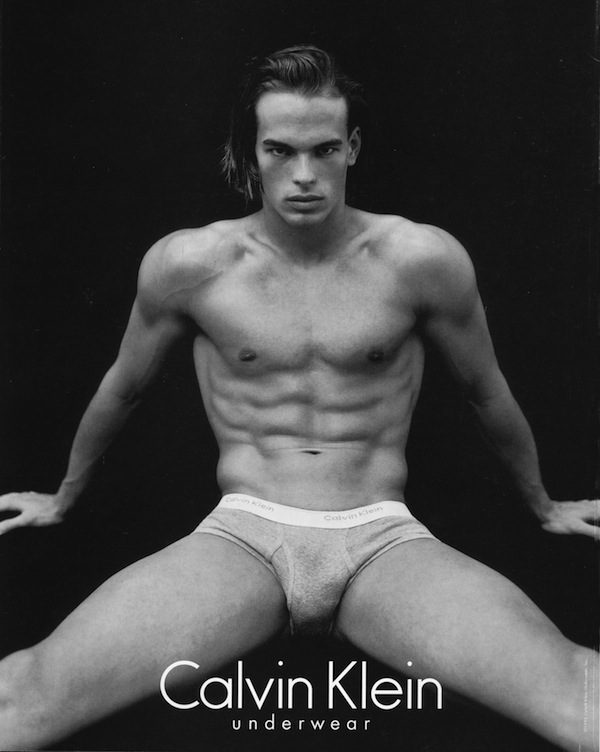

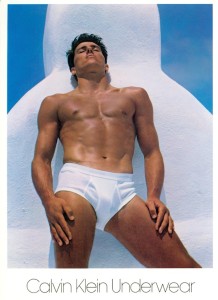

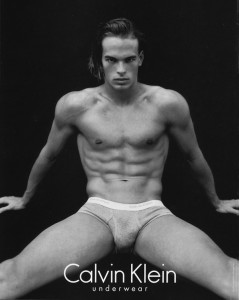

Although underwear marketing of the 1970’s had clearly broadened both the appeal of the muscular æsthetic and the eroticization of men’s underwear, according to many fashion historians, the clincher that set the pattern for the sexual objectification of the male form in marketing was the underwear campaign initiated in 1982 by Calvin Klein. The story of photographer Bruce Weber and Olympic pole vaulter Tom Hintnaus modeling CK white cotton briefs is legendary. Calvin Klein and Bruce Weber raised the bar for mass marketing underwear, and competitors rushed to preserve their market share with comparable imagery. The floodgates were opened, and a myriad of new presentations—new for the straight market, that is—with bulging muscles and bulging briefs filled magazine pages and towered overhead on billboards (Figures 12 and 13). Even TV commercials began to depict men in assorted scenarios dressed only in their formfitting underwear. Narratives in ads ran the gamut from high art to soft-core porn, made possible by thirty years of the gay factor in marketing men’s underwear and swimwear.

Author’s Note: This essay is an edited excerpt from History of Men’s Underwear and Swimwear , by Daniel Delis Hill. Questions and comments are welcome at www.DanielDelisHill.com.

References

Jobling, Paul. Man Appeal: Advertising, Modernism, and Menswear. Berg, 2005.

Cole, Shaun. Don We Now Our Gay Apparel: Gay Men’s Dress in the Twentieth Century. Berg, 2000.

Daniel Delis Hill is the author of several books on fashion, including History of World Costume and Fashion (2010).