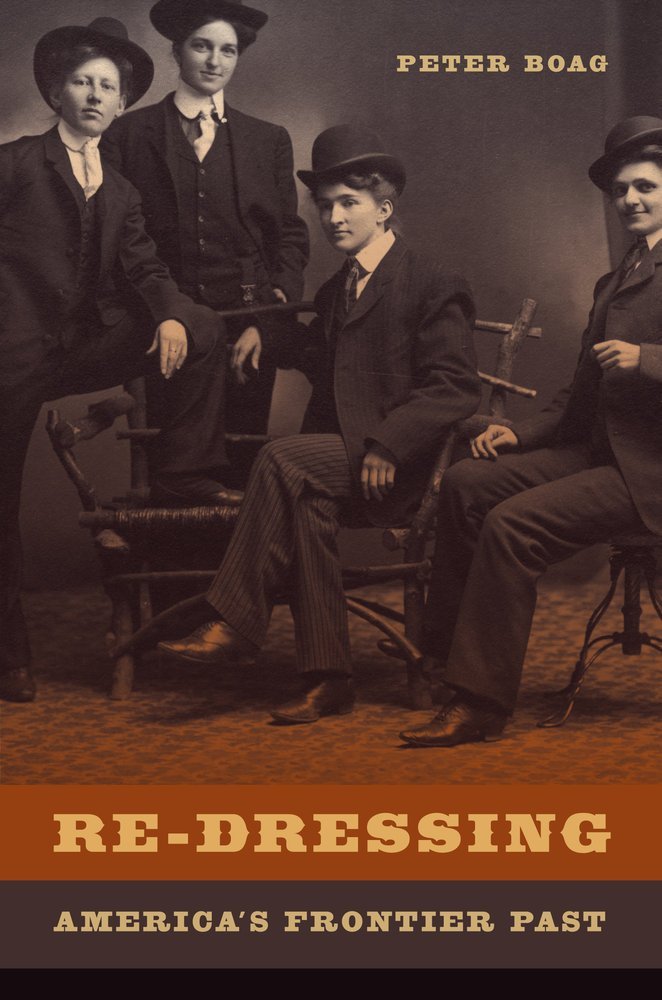

Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past

by Peter G. Boag

University of California Press. 272 pages, $39.95

JOE MONAHAN’S neighbors were shocked. The fall of 1903 was short and winter came early. Tough and self-sufficient, Joe had come to the Mallory ranch complaining of illness and he didn’t look well. Shortly after his arrival, he died in the warmth of his neighbors’ home. The shock came when they went to prepare Joe’s body for burial: grizzled Joe Monahan was a woman.

Peter Boag argues in Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past that such scenarios were commonplace in the West in the decades between 1850 and 1920. Although the townspeople talked and tittered, cross-dressers were a widespread social phenomenon of this era, and the transformation could go in either direction. For biological women, the frontier was a man’s world. There were adventure and wealth to be had, and becoming a man was a way to seize upon opportunity. Safety was another reason for appearing masculine. Then there were those who were essentially incognito in order to escape the consequences of criminal behavior back home. Then, too, there were undoubtedly many women who genuinely believed themselves to be boys from birth.

For smooth-faced young men, cross-dressing was often a part-time affair: it was common for men to dress as women for dances and parties because biological women were scarce. Such men impersonated women to entertain other men. In some Native American communities, “berdaches” were encouraged to embrace femininity, and early frontiersmen took note and looked askance at them (though their Anglo neighbors were often doing the same thing). Like the women, some men would cross-dress as a disguise to evade capture by the authorities. And then there were surely men who thought of themselves as female and chose to live accordingly.

Being arrested for wearing clothes of the opposite sex was a common experience for both men and women. Cross-dressers were often shunned, which was particularly onerous in a vast and sparsely populated region. Interestingly, however, their partners were generally accepted, regardless of the “gay” or “straight” implications of the pairing—so long as the partner was gender-normative. Boag offers lots of excellent examples to support his claim that these stories have been largely hidden from history. He cites case after case of women and men dressing as the other sex for perfectly understandable reasons.

Fascinating though it is, this is not a book for the beach but is instead a scholarly tract that often reads like a dissertation. Boag faced a research problem due to a dearth of first-hand accounts—many of his subjects were illiterate or just never got around to telling their story—forcing him to rely on accounts from neighbors and townspeople who had “suspicions” about someone. Often these sources include rudimentary diaries and letters, plus old newspaper accounts that veer close to sensationalism. Still, the recovery of these accounts over a century later is an important step toward understanding a hitherto hidden aspect of our frontier past.

________________________________________________________

Terri Schlichenmeyer is a writer based in LaCrosse, Wisconsin.