Intimacy and Sexuality in the Age of Shakespeare

Intimacy and Sexuality in the Age of Shakespeare

by James M. Bromley

Cambridge Univ. Press. 210 pages, $95.

This detailed, scholarly study explores the variety of sexuality and intimacy described in several literary works from the English Renaissance. Examining poems, plays, and so-called “closet dramas,” Bromley argues that the writers from this era challenged the notion of monogamy as the ideal form of intimacy, and explored alternative sexual possibilities such as anal eroticism, masochism, and homoeroticism. Even though monogamous hetero relationships ultimately prevail in each of these works, these alternatives are supported as viable possibilities, thus expanding the idea of what it means to be intimate. Bromley begins with Christopher Marlowe’s poem Hero and Leander, asserting that the many references to classical mythology in the poem, such as the tragic tale of Venus and Adonis and the many instances of gods abducting mortals for sexual pleasures, demonstrate the possibilities of “short-term, situational intimacy.” For example, Hero and Leander are deeply intimate and loving for a brief time, as their situation permits, but could not be considered a “couple” by typical Renaissance standards. Bromley also considers Shakespeare’s plays All’s Well That Ends Well and Cymbeline as linking intimacy with marriage. The main male characters initially resist this idea, instead suggesting that the anus can provide a “form of embodiment, pleasure, and affection.” They ultimately end up in a “traditional” marriage, but the alternative appears for a fleeting moment onstage. While it presents an intriguing thesis, this book seems mainly intended for scholars. Bromley’s method involves a close, subtle analysis of the texts. Dense academic jargon covers the page, and the works used are often obscure. However, Bromley’s suggestion that, in our determination to achieve same-sex marriage equality, we also consider other alternatives to monogamous heterosexuality is a worthwhile one.

Charles Green

Red Nails, Black Skates: Gender, Cash,

Red Nails, Black Skates: Gender, Cash,

and Pleasure On and Off the Ice

by Erica Rand

Duke University Press. 320 pages, $23.95

When Erica Rand competed at the Adult Nationals as a figure skater, she expected to be criticized for her botched spins and jumps, but it turned out she was criticized for other, more surprising reasons. An art professor at Bates College in Maine, Rand was in her forties when she started competing as an amateur skater, but it wasn’t her age that attracted attention either. As a self-proclaimed “queer femme,” the criticism she faced related to her unwillingness to conform to the strict rules of self-presentation that the judges enforced. This book is a compilation of essays that encapsulate Rand’s thoughts on being a figure skater and her experience of the homophobia, classism, racism, and sexism that prevail in the sport. She finds the judges to be rigid to the point of being pedantic, insisting upon very gender-specific outfits, boots, and choreography. Choosing not to accept these standards, she found herself at odds with competition officials. What’s more, for all their implicit expectations, Rand often found it hard to figure out what the judges actually wanted, what they would find permissibly “feminine” for a female skater. In the end she made her peace and did quite well as an amateur skater in the Adult Nationals, but decided to leave the rigidity of that field and concentrate on the far less regimented Gay Games. Having spent most of her adult life in the world of art and feminist politics, Rand learned firsthand how the sports world is dominated by inflexible gender codes and heterosexual scripts.

Sandra Scholes

The Letter Q: Queer Writers’

The Letter Q: Queer Writers’

Notes to Their Younger Selves

Edited by Sarah Moon

Arthur A. Levine Books. 272 pages, $17.99

What if you had known “then” what you know now? How would your life had been different? Such was the premise of Sarah Moon’s challenge to a few dozen GLBT writers: to consider what they’d say to their younger selves if they could go back in time. The result is this quirky anthology, which brings together their accumulated wisdom when reflecting on their earlier lives. Many structured their replies as letters to themselves as adolescents and young adults. A few passed on investment advice, such as Jewelle Gomez, who urges the young Jewelle to capitalize on Twilight: “Maybe you should think about writing vampire stories, they might come back into fashion someday.” The messages aren’t all happy, or even encouraging. David Levithan calls himself out for bullying a teacher he didn’t like and for being cruel as a means of self-protection. Diane DiMassa’s letter is as wonderfully shouty and frantic as her Hothead Paisan comics, but not without encouraging words: “Look how much you have already survived. You are coping!” Gregory Maguire’s letter manages to be sweetly direct, warning himself “not to succumb to the narcissism of loneliness too much,” then screaming about Harriet the Spy and how the things we held dearest as kids still endure. The Letter Q gives GLBT writers a chance to use the raw material of their lives to ponder how things might have turned out otherwise, whether for better or worse. Part of the pleasure here is in knowing that these budding writers all grew up to fulfill at least some of their youthful aspirations; these are life stories in which things have mostly worked out for the best.

Heather Seggel

Banned in Boston: The Watch and Ward Society’s Crusade Against Books, Burlesque, and the Social Evil

Banned in Boston: The Watch and Ward Society’s Crusade Against Books, Burlesque, and the Social Evil

by Neil Miller

Beacon Press. 224 pages, $18. (paper)

Why did Boston not become New York City? Why did it start calcifying in the late 19th century? And why did the city remain a backwater until the 1960’s, when its leaders woke up and smelled the coffee? Neil Miller addresses these questions in Banned in Boston. As luck would have it, one of the first targets of the Watch & Ward Society in Boston was a new edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. They wanted cuts to his text. Whitman finally canceled his contract with his Boston publisher and went with an imprint in Philadelphia, and the phrase “Banned in Boston” was born. As Miller shows, one of the impulses behind the censorship campaigns was revulsion by the elites at the changing demographics and new technologies—the movies, followed by television. When H. L. Mencken came to Boston, he famously challenged the bluenoses to sell a copy of his magazine, American Mercury, the current issue of which had a racy contribution in it; and Mencken was arrested. At the trial, he was found not guilty of corrupting the morals of the youth of Boston, few of whom were believed to subscribe to Mr. Mencken’s literary publication. But this circus went on and on, for decades. And the funny thing was, when books were banned in Boston, one could hop on the subway or bus, go to the more enlightened Cambridge, browse, and buy. Why are the provincials so provincial? Miller’s history is helpful in explaining how “the Athens of American” veered toward Sparta for a time.

John Mitzel

Montreal’s Gay Village: The Story of a Unique Urban Neighborhood through the Sociological Lens

Montreal’s Gay Village: The Story of a Unique Urban Neighborhood through the Sociological Lens

by Donald W. Hinrichs

iUniverse. 213 pages, $18.95 (paper)

Montreal’s gay neighborhood, dubbed “the Village” in the ’80s, is now grappling with many of the same questions as are many other places once thought of as GLBT districts in American and European cities. In a world where gay people now seem so much more acceptable and less threatening than they were, do we still need to ghettoize ourselves in such neighborhoods? Hinrichs, a lecturer in sociology at Montreal’s McGill University, traces the history of Montreal’s Gay Village, analyzing why it became a hub for gay life and considering whether it ever really represented the spectrum of GLBT life rather than the interests of privileged gay men. While he clearly does lean favorably towards the history of the Village and what he sees as its continued value and relevance, Hinrichs is careful to quote a broad range of opinions on these questions. There are historical anecdotes, discussions of cultural references to the Village (in literature, theatre, TV and film), and dispelling of certain urban legends about why the city’s gay district moved due east in the late 70’s and 80’s. (Some have argued it was a homophobic municipal government that wanted to harass gays out of the city center; Hinrichs argues it had more to do with the basic issue of rapidly rising rents.)

Despite its academic tone, Hinrichs keeps the writing pleasingly accessible. Insofar as the central existential question that hangs over Montreal’s queer ’hood is being asked in many cities around the world, the book has applicability beyond the major focus of research.

Matthew Hays

Margins of Tolerance : Stories

: Stories

by Eric Sasson

Livingston. 228 pages, $19.95

This affecting collection of short stories reveals the tensions between fitting into mainstream society and standing out as unique individuals. With settings ranging from South Africa to the American suburbs, these stories aim to take readers out of their comfort level as they explore locations and situations that both frighten and arouse. In some cases, this happens in exotic locations, far from the familiarity of home. “Body and Mind” finds a couple introducing another man into their bedroom while vacationing in Las Vegas. Found through a hook-up site, the young man appears to fit in quite well with the two other men at first, but, soon enough, the relationships among all three participants become complicated and even troubling. “Cruising” celebrates the culture of sex in the steam rooms of cruise ships. The narrator proudly quips that such cruising “is our God-given right,” drawing a sharp line between the gay passengers (including the entertainers, Pilates instructors, and waiters) and the straight ones, arguing that because heterosexuality is so pervasive on cruise ships, the steam room is the only place where gay men can unashamedly be themselves, and even “let off a little steam.” The title story nicely demonstrates the difficulty of settling down in a relationship. Parker and his partner, after several years of “the bar circuit, the clubs, the parties, Fire Island, Provincetown,” buy a house in suburban New Jersey. Almost immediately, Parker’s artist partner, who narrates, feels like he’s falling into a life of conformity, and he questions whether this is truly what he wants or if he’s just following Parker’s dream. When he notices the neighbor’s teenage son checking him out, he makes a reckless choice that threatens everything he has worked for.

Charles Green

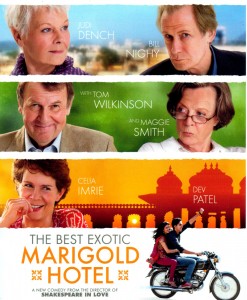

The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel

The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel

Directed by John Madden

Fox Searchlight

This movie, which is clearly targeting an older mainstream audience, turns out to have a surprising gay subplot that takes center stage by the film’s end. Marigold offers a cross-section of British pensioners—a married couple, a recent widow, a divorcée looking for her next husband, a never-married housekeeper, an aging playboy, and a gay man—who’ve come to live in India for a variety of reasons, most of them related to financial necessity or declining health. The sheer density of events in Marigold is worthy of a Seinfeld episode. In rapid succession we’re introduced to seven characters and learn why they’re planning a move to India and enough about their back story to understand why they are the way they are, whether bitter or sanguine, resigned to old age or still fighting for something. The best-developed story is that of the gay character, who was raised in India but spent his adulthood in the UK as a high court judge. Graham has come to India to track down the man with whom he fell in love and had a torrid affair many years ago, a man whose life was ruined—or so he assumes—when the affair was discovered by family members. Having left India with the situation unresolved, Graham has been haunted all his life by his lover’s fate. Graham is completely open about being gay, and his fellow travelers—except for a gal who was hoping for a romp—don’t bat an eyelash. What’s more, the reunion of the two men is handled with the same respect as every other meeting or farewell in the film, though it is surely the most poignant.

Wendy Fenwick