“PHOTOGRAPHY is a kind of primitive theater, a kind of tableau vivant,” Roland Barthes remarked, shifting attention away from the medium’s significance as an evolutionary event in the history of pictorial representation. Viewing photography in this way, as a dramatic art, enables us to think about the photograph as an arena in which to act rather than a stilled frame out of reality’s filmic continuum. Since theatrical performance invariably requires an audience, looking at photography through the lens that Barthes proposes in Camera Lucida brings the spectator’s role in the production of meaning into focus. This, in turn, opens new realms of insight into a range of photographic as well as theatrical practices and has specific applications with respect to the collaborative work generated by lesbian artists Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore in the early 20th century.

The photographic œuvre featuring Cahun has earned acclaim and circulated in contemporary shows and publications under the banner of “self-portraiture.” I take exception to this classification on several counts. Hardly anyone would deny that these images result from some sort of collaboration, since Cahun could not possibly have realized most of them without assistance. This observation alone suffices to compromise the word “self” in the generally accepted formulation “self-portraiture.” Yet the categorical designation has provided scholars, curators, and other viewers with what seems a viable term of convenience. A number of art historians have compared Cahun’s photographic tableaux to those of the contemporary artist Cindy Sherman—who engages assistants to produce the photographic compositions that she enacts and/or envisions. While the designation “self-portraiture” unquestionably elides important aspects of Sherman’s representational process and project, framing the collaborative work done by Cahun and Moore as self-portraiture has additional consequences. Cahun’s collaborator, after all, was not a professional assistant but her lifelong mate. What social prejudices and artistic hierarchies does the erasure of Moore accommodate, and to what extent did the two artists foresee, forestall, or foreclose—or foreordain—this erasure?

Let us look for answers—that is to say, statements of or about co-production—in the work itself. The Jersey Heritage Trust collection on the Isle of Jersey (one of the UK’s Channel Islands), where Cahun and Moore lived in the last decades of their lives, preserves numerous negatives and prints that make both the fact and the thematic of collaboration apparent. Some shots, for example, picture first Cahun and then Moore posing alternately in the same setting, as in the following (Cahun is on the left):

In addition to these reversals, the device of doubling and other metaphorical and formal references to artistic and emotional complicity—such as the intrusion of the photographer’s shadow upon the space of the photograph—affirm Moore’s engagement in less literal ways. A photograph taken circa 1915 representing the still adolescent-looking Cahun posing against a massive formation of granite offers a case in point. Moore casts a shadow on the scene (and upon the photographic paper) in the lower right hand corner of the composition—just where we are conditioned to look for the artist’s signature. This doubly indexical mark could be understood as a sort of artistic contract that the couple would honor for nearly forty years. The silhouette, which draws the photographer and the viewer into the frame of the picture, allows us to imagine the sitter’s expressive acts coming to fruition in the eyes of an unseen but present observer to whom those gestures are addressed.

At the very least, it would seem expedient to remove the hyphenated “self” from the label “self-portraiture” and to reconceive of portraiture, like photography, as a theatrical pursuit. Certainly portraiture as practiced by Cahun and Moore performed something other than the traditional functions of commemoration or classification. It appears to have served, on the contrary, to destabilize the notion of “self” that the portrait genre has historically upheld—and, more constructively, to provide an arena of experimentation within which the photographer and the subject could improvise alternative scenarios of social, sexual, and artistic practice. Within this arena, Cahun and Moore—subject to the constraints that faced “the weaker sex” in patriarchal societies in their time—could act up, act out, enact their desires, and act upon their convictions.

The creative alliance between Cahun and Moore formed in provincial Nantes, where, in 1909, the fifteen-year-old Lucie Schwob, who would later adopt the pen name Claude Cahun, encountered the seventeen-year-old beaux-arts student Suzanne Malherbe—Marcel Moore—in what they both described as “une rencontre foudroyante” (a lightning-strike connection). Eight years later, Cahun’s father, Maurice Schwob, a prominent publisher, married Moore’s widowed mother, Marie-Eugènie Rondet Malherbe, entwining the two “daughters” in a familial relationship that undoubtedly facilitated their artistic collaborations and provided a degree of social cover for their intimacy.

Cahun and Moore rehearsed and photographically recorded the private performances that they staged in their “bedroom carnival” throughout the 1910’s, creating something like a new iconography of gendered subjectivity in the process. During these years, Cahun also penned new scripts for misunderstood heroines (Sappho, Cinderella, Salomé, Eve) and Moore applied her formal training as a graphic artist to the creation of pen-and-ink illustrations. “Feminism is already in the fairytales,” Cahun remarked, suggesting that the slightest shift in the angle of view will make the suppressed content plain. Cahun reformulated a dozen or so fables from the viewpoint of their “misunderstood” heroines and contributed several, including “Judith, la sadique,” to the prestigious literary journal Mercure de France for publication. She and Moore intended to publish a fully illustrated version of the collection under separate cover, but never realized this ambition. We encounter Moore’s sardonic humor in the face of the castrating Judith that she created to illustrate this project, a face that bears more than a passing resemblance to that of her partner. The typescripts and illustrations that survive in the Jersey Heritage Trust collection enable us to imagine how such a publication might have turned out. Yet the circumstances that prevented Cahun and Moore from bringing the project to fruition remain a mystery.

The couple had already succeeded, after all, in publishing one illustrated book, Vues et visions, in 1919. As the title implies, the volume juxtaposed paired vignettes transforming contemporary “views” (two weathered skiffs tethered to an abandoned pier in the Brittany seaport of Le Croisic) into poetic “visions” (the stone figures of two boys permanently united in loving proximity upon a tomb in ancient Greece). An illumination by Moore frames each page of text Cahun wrote.

Each set of illustrations forms a sort of stage proscenium converting a double-page spread into a theatrical space within which the commonplace stuff of everyday life can reveal, through poetic transformation, new levels of meaning. More specifically, the images reverberate with homoerotic double sense, participating in a homophile reconstruction of antiquity underway since the late 19th century. Indeed, this album’s publication could be viewed as Cahun and Moore’s artistic coming out, since it undoubtedly raised their public profile as an artistic couple and affirmed (albeit in code) their affection for each other and the legitimacy of their bond.

A year after the publication of Vues et visions, Cahun and Moore migrated from the provinces to Paris and opened the doors of their left-bank atelier to a dynamic population of intellectuals, artists, and political activists. Their address book (also archived in the Jersey Heritage Trust collection) traces the cultural and intellectual parameters of interwar Paris. The names noted here offer evidence of the couple’s ties to the theatrical establishment (Edward de Max and Marguerite Moreno of the Comédie Française) as well as their engagement with experimental theater (in association with Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Castan, Georgette Leblanc, Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff, Beatrice “Nadja” Wanger, and Berthe D’Yd).

From 1925 to 1927, Cahun and Moore belonged to Les Amis des Arts Esotériques and participated in  the life of the Théâtre Esotérique, founded by Berthe D’Yd and Paul Castan. The troupe specialized in what one reviewer described as “dramatic tableaux that made one dream, because of the preciousness and refinement of the palette, of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé.” Cahun assisted with, and occasionally performed in, the theater’s esoteric spectacles—which included Sâr Péladan’s Babylone, La Prométhéide, and Oedipe et le Sphinx. These productions were staged in a cultural center founded by the Société Théosophique. Moore, by then an accomplished designer, offered her services to the company. The theatrical and fashion designs preserved in the Jersey Heritage Trust archives leave little doubt as to Moore’s professional promise in this realm. Her schematic costume drawings are sure-handed and expressive. Costume and set designs by Moore for the Théâtre Esotérique have never come to light. However, her photographs of rehearsals and graphics for handbills, posters, programs, and other promotional material attest to her involvement.

the life of the Théâtre Esotérique, founded by Berthe D’Yd and Paul Castan. The troupe specialized in what one reviewer described as “dramatic tableaux that made one dream, because of the preciousness and refinement of the palette, of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé.” Cahun assisted with, and occasionally performed in, the theater’s esoteric spectacles—which included Sâr Péladan’s Babylone, La Prométhéide, and Oedipe et le Sphinx. These productions were staged in a cultural center founded by the Société Théosophique. Moore, by then an accomplished designer, offered her services to the company. The theatrical and fashion designs preserved in the Jersey Heritage Trust archives leave little doubt as to Moore’s professional promise in this realm. Her schematic costume drawings are sure-handed and expressive. Costume and set designs by Moore for the Théâtre Esotérique have never come to light. However, her photographs of rehearsals and graphics for handbills, posters, programs, and other promotional material attest to her involvement.

The experience with the Théâtre Esotérique seems to have edged the couple toward a more serious career commitment to theater. Subsequently, Cahun auditioned before Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff, whose work was respected within vanguard theatrical circles across Europe. Cahun had second thoughts, though, and declined an invitation to join the company, fearing that fragile physical and mental health would prevent her from keeping pace with occupational demands. She remained in the Pitoëffs’ orbit, however, and closely followed their theatrical ventures.

Indeed, she and Moore seem to have attended the full spectrum of divertissements available in Paris in the 1920’s: poetry readings at Adrienne Monnier’s bookstore, academic conferences at the Sorbonne, psychiatric teaching demonstrations at Ste. Anne’s Hospital, performances of the Russian Ballet at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Hollywood movies and jazz-band jam sessions. (Cahun occasionally reviewed such events for the literary journal La Gerbe, published by her father.) Their conversancy with all echelons of Parisian performance and visual culture enriched the performances that Cahun and Moore continued to stage and photograph at home in their Montparnasse atelier.

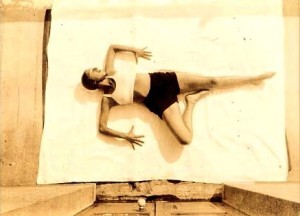

The level of their sophistication with respect to performance reveals itself in a series of aerial shots taken from an upstairs window of their building. Within Moore’s bird’s eye view, Cahun acts out something akin to semaphore code in the courtyard below. A black and white swimsuit abstracts the contours of her prone body and defines her form against the white sheet that serves as a backdrop.

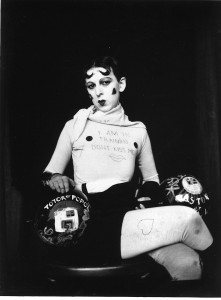

At the other end of the performance spectrum, photographs from this decade picturing Cahun “in training” contain multiple references to more popular pastimes such as boxing and matinee theater. Costumed in boxer shorts, wrist guards, and a leotard inscribed with hearts and the admonition “Don’t Kiss Me I’m In Training,” Cahun balances weights bearing the names of the comic heroes Totor and Popol in her lap, and preens for the camera in a manner that accentuates signs of hyper-femininity: paste-on nipples, painted-on lips, and lacquered-down spit curls.

Toward the end of this spectacular decade, Cahun and Moore joined an obscure theater company, Le Plateau, directed by Pierre Albert-Birot, whom they had probably encountered at the Théâtre Esotérique. Albert-Birot—a typographer, poet, and visionary—had long dreamed of venturing into the dramatic arts, and Cahun and Moore numbered among the handful of collaborators that he recruited from Paris’s theatrical margins. Cahun performed as Satan (Le Diable) in an adaptation of a 12th-century mystery play about Adam and Eve, Les Mystères d’Adam, produced by Albert-Birot in March of 1929. She earned critical praise for her role as Bluebeard’s wife (Elle) in a feminist parable, Barbe bleue, and also performed as the character Monsieur in a satire titled Banlieu (which was not as well received). Moore apparently did not produce costumes or sets for Le Plateau, but documented several of the plays photographically, including those in which Cahun performed. Albert-Birot mapped out his research program for new modes of dramatic and poetic expression in a “Programme-Revue” also named Le Plateau. Cahun contributed excerpts of her writings to the publication, where Moore’s portraits of the members of the company were reproduced.

The convictions that Cahun and Moore shared with Albert-Birot include a profound mistrust of realist representational traditions, whether literary, dramatic, or pictorial. “We challenge realism because the realism we are given is false,” Albert-Birot declared, “we do not believe that it is real. Today, most actors reproduce reality from the outside, whereas to reconstitute reality from the inside is to create; it is the beginning of creation.” With Apollinaire, Albert-Birot envisioned a theater in the roun d where the audience, activated as participants, occupied the center of the dramatic arena. This, too, struck a chord with Cahun and Moore, whose work explored the negotiation of meaning in similarly multilateral terms.

d where the audience, activated as participants, occupied the center of the dramatic arena. This, too, struck a chord with Cahun and Moore, whose work explored the negotiation of meaning in similarly multilateral terms.

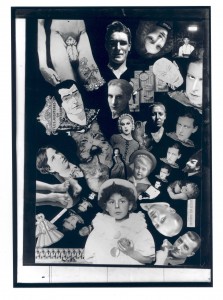

It is easy to understand why Albert-Birot’s ideas about theatrical play (performance as a “mode of research” into new forms of social and artistic interaction) would have inspired Cahun and Moore. Even after the Théâtre du Plateau disbanded, they remained close to its leader. What’s more, their encounters with the Théâtre du Plateau and Le Théâtre Esotérique emboldened Cahun and Moore to widen their circle of artistic collaborators and to forge alliances with activists in the surrealist milieux. These milieux became the artistic and intellectual context in which Cahun and Moore created their second major collaborative publication, Aveux non avenus (“disavowed confessions”). The book, an anti-realist literary mosaic assembled by Cahun, features photo-collage illustrations that Moore composed from the store of pictures she had taken of her lover, including several from Théâtre du Plateau performances. Amid images of Cahun’s avatars and cultural icons (including Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas), Bluebeard’s Wife, Elle, attracts our attention at the center of the scrambled family album (above) that introduced the book’s first chapter, for instance.

The emphasis on the stage career within the literary/pictorial framework of Aveux non avenus signals the relevance of theater as a model for the couple’s other artistic initiatives. Albert-Birot—who strove to free expression from the falsehoods of a commodity-driven cultural system—chose to publish excerpts from Aveux non avenus in his short-lived review Le Plateau. The book, like Albert-Birot’s endeavors, targets narrativity, realism, the cult of celebrity, and the cult of self.

IN 1932, Cahun joined the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, where she encountered the surrealist leader André Breton. She (and more rarely Moore) signed, and helped to compose, many of the political tracts generated by Breton and his supporters during the 1930’s. In 1934, Cahun published Les Paris sont Ouverts (“the bets are open”), a brilliant defense of poetry’s political potential, which earned her Breton’s grudging respect (despite his homophobia). Cahun participated regularly in surrealist demonstrations, strategy meetings, publications, and exhibitions during this period, while Moore remained active behind the scenes.

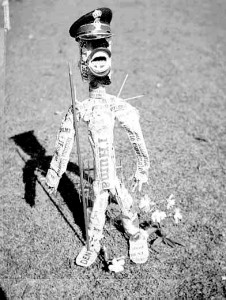

As the surrealist group—and, moreover, the political left in France more generally—divided into antagonistic factions, Cahun sided with Breton. The acts of puppet theater that she staged and photographed at this time dramatize positions consistent with those that she advanced in collective publications such as Dissolution de Contre-Attaque (1936). In one mise-en-scène, for instance, a tiny German officer whose body Cahun had crafted out of the communist newspaper L’Humanité signals the merger of two totalitarian schools of thought, that of Hitler and that of Stalin (pictured below).

In retrospect, it is tempting to view these “puppets” as harbingers of the creative acts that Cahun and Moore would stage on the Isle of Jersey during the German Occupation. However, in 1936, the idea of moving to Jersey—not to mention trepidations about the occupation of Paris—may not yet have broken the horizon of their conscious minds.

A year later, however, Cahun and Moore packed up their affairs and moved to St. Brelades, a remote parish on the isolated Channel Island of Jersey. One can only speculate as to their motives. Disillusionment with the political climate in Paris—outbreaks of anti-Semitism, the violent schisms that divided the left and broke up their circle of friends—undoubtedly influenced the decision to seek a more harmonious environment. But why the Isle of Jersey? They had vacationed on the island and knew that it would offer them a haven where they could consider their options in relative serenity. But this was also true of Le Croisic, in Brittany, which had the advantage of being more convenient to Paris. The Channel Islands, on the other hand, were a world apart, a world in between—not part of the United Kingdom, closer to the Normandy coast, a historic place of piracy and literary exile. Was it the neutrality, the history of sanctuary, the cultural hybridity and political inconsequence that attracted the couple? They had discussed expatriating to Canada—but Jersey, at least, lay close enough to France’s shores to permit the maintenance of bonds of affinity and affection. (Henri Michaux, Nadja, Henri Barbier, Breton, and Jacqueline Lamba visited them on the island, for instance.)

Not long after Paris was invaded by German military forces in 1940, Jersey suffered the same fate. Cahun  and Moore decided to stand their ground rather than flee to England as fully half of the islanders had. In fact, they launched a two-woman anti-Nazi propaganda operation, blanketing every part of the island with handmade tracts. Cahun’s war memoir describes how she and Moore succeeded in creating the illusion of a large-scale resistance movement. After several years at risk, they were arrested for high crimes of treason and were subjected to arduous interrogation because they refused to reveal the names of their male collaborators. The investigating officers found it impossible to believe that two middle-aged women had conducted such a daring campaign “all alone.” “They were forced, at the end of the day, to condemn us without believing in our existence,” Cahun concluded. This tour-de-force performance, under fire, represents the end-logic of the couple’s career of theatrics: from the photo play of two defiant lovers to collective acts of cultural subversion; from the (fragile) dream of political community to acting as one (as if they were many) in resistance to military domination.

and Moore decided to stand their ground rather than flee to England as fully half of the islanders had. In fact, they launched a two-woman anti-Nazi propaganda operation, blanketing every part of the island with handmade tracts. Cahun’s war memoir describes how she and Moore succeeded in creating the illusion of a large-scale resistance movement. After several years at risk, they were arrested for high crimes of treason and were subjected to arduous interrogation because they refused to reveal the names of their male collaborators. The investigating officers found it impossible to believe that two middle-aged women had conducted such a daring campaign “all alone.” “They were forced, at the end of the day, to condemn us without believing in our existence,” Cahun concluded. This tour-de-force performance, under fire, represents the end-logic of the couple’s career of theatrics: from the photo play of two defiant lovers to collective acts of cultural subversion; from the (fragile) dream of political community to acting as one (as if they were many) in resistance to military domination.

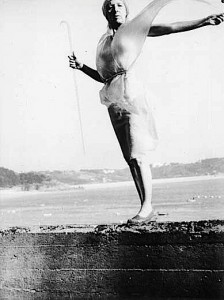

When I look at Moore’s pictures of Cahun taken just after the liberation, when the two re turned to their home to dance along the fortifications that the Germans had built in their garden, a phrase from Aveux non avenus springs to mind: “Victorious! Sometimes victorious over the most atrocious inhibitions, a last-minute maneuver corrects a shadow, an imprudent gesture—and beauty is reborn.” I think, too, of the enigmatic pictures that Moore later took of another wall, at the end of a smaller garden, looking out over the same sea from the modest house that she purchased for herself after Cahun’s death. There I see an empty garden wall viewed from Moore’s back yard, a naked stage, haunted by the absent subject of Moore’s photographs, life-long object of her devotion and desire.

turned to their home to dance along the fortifications that the Germans had built in their garden, a phrase from Aveux non avenus springs to mind: “Victorious! Sometimes victorious over the most atrocious inhibitions, a last-minute maneuver corrects a shadow, an imprudent gesture—and beauty is reborn.” I think, too, of the enigmatic pictures that Moore later took of another wall, at the end of a smaller garden, looking out over the same sea from the modest house that she purchased for herself after Cahun’s death. There I see an empty garden wall viewed from Moore’s back yard, a naked stage, haunted by the absent subject of Moore’s photographs, life-long object of her devotion and desire.

Tirza True Latimer is chair of the graduate program in visual and critical studies at California College of the Arts in San Francisco.