MARGARET ATWOOD said in a 1995 lecture: “If you write a work of fiction, everyone assumes that the people and events in it are disguised biography—but if you write your biography, it is equally assumed you’re lying your head off.” At the risk of being accused of one or the other, I wrote two memoirs, The Queen of Peace Room back in 2002 and Street Angel in 2014. Both memoirs tell the story of my life in a small Newfoundland town in the 1940s and ’50s, chronicling sixty years of a life that began in a complex, secretive family followed by a move to art school in Pittsburgh at the age of eighteen and eventual arrival in New York City during the explosive 1960s. The Queen of Peace Room is set in the present—a week-long retreat at a secluded house—as I reflect on fifty years of life to date. Street Angel, the sequel, concentrates on the 1950s in Newfoundland. I’m working on the third book that covers a window of time from 1960 to 1969.

I was completely naïve when I left Newfoundland and went from twelve years of schooling with Catholic nuns to art school in Pittsburgh and on to 1960s New York, where I was involved in underground theater and stage-managed a very young Bette Midler and also worked with a young Bernadette Peters. Then there were the poetry readings with Peter Orlovsky and Moondog, riding in a VW bus with Allen Ginsberg, working with Tom Eyen, Sam Shepherd, Lanford Wilson, Joe Cino, John Guare, and a host of people at a small café theater called the Caffe Cino. The Cino shaped who I am. Most of the cultural happenings of the ’60s were impromptu, unexpected, accidental. and unexplained. No one had money; we pooled what we had or did without.

Those years for me were all about the anti-Vietnam War movement, poetry readings, demonstrations, and antiwar marches, which meant walking beside thousands of men who looked like Jesus. People had liquid codeine in one hand and brown rice in the other. I was an impostor for the TV show To Tell the Truth, received the Langston Hughes Award for poetry, and saw people die on the street from heroin overdoses. Somewhere in there I worked for an interior design showroom. I saw people out of their minds—barefoot on sidewalks. Ginsberg’s Howl came to life right in front of me. I walked through the lines of Howl every day of my life, for years. I worked at the Lighthouse for the Blind and worked with blind children. In retrospect, it seems like science fiction—except I have the photo documentation!

In The Queen of Peace Room I compare the ’60s to the Wild West. Anything was possible. Half a million people chanted peace in a field in upstate New York. John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Robert Kennedy were all assassinated. A man walked on the moon!

For those who were there, the 1960s began differently for everyone. For me, they began in the ’50s. That’s because of the nuns. At the behest of the Catholic Church, and because I was born into a home with a Catholic father and a non-Catholic mother, I was, by Catholic Church decree, baptized in the Catholic Church and raised Roman Catholic. That resulted in twelve years of torturous and disheartening education by women with names like Sister Mary Saint John the Baptist, Sister Mary Saint Finbar, Sister Mary Zorba the Greek. The nuns had their own interpretation of Jesus, Mary, and discipline.

The nuns in the 1950s made me want to escape, and that’s why my ’60s began in the ’50s. After high school, I moved to Pittsburgh to study interior design, and after graduation moved to New York, my mind filled with questions. The streets, the news, and the conversations were dominated by Saigon, Hanoi, and marching. And with underground theater, civil rights, folk music, Frye boots, long skirts, and draft-card burning. We were unknowingly the creators of a cultural revolution.

As an indication of how quickly things were escalating, in November of 1963 there were 16,000 American soldiers in Vietnam. Three years later, that number had escalated to over 400,000. The number of Vietnamese killed—in both the North and the South—was deliberately manipulated to justify the war. We were told we were winning, that it was worth the sacrifice, but this was clearly a lie.

One phase of my life was consumed by political poetry, Bob Dylan, underground theater, and Allen Ginsberg. Aside from the Ginsberg poetry readings I attended, and peace demonstrations, and readings with Peter Orlovsky and the blind writer-composer Moondog, and listening to Ginsberg sing and chant and play the harmonium—a lap-sized wooden organ with hand-pumped bellows—and listening to the rhythms of his reading voice, there were two specific personal encounters in 1966. One was on the Lower East Side, and the other in Sundance, Pennsylvania.

I saw Ginsberg one hot summer afternoon, in late June or July, walking toward his apartment in the East Village. We were in the same block but walking in opposite directions. He was walking east, I was walking west. A group of boys, maybe ten years old, had opened a fire hydrant, and water was gushing into the air, over the street and the sidewalk. A geyser of water towered over half the block. The boys were shouting and screaming and racing in circles, ecstatic with what they’d created. I debated, as I approached cascading surge, whether I should cross to the other side of the street, or scream and tell them to close the valve and shut off the water.

I looked at Ginsberg as he proceeded directly toward me and the edge of the geyser. Without speaking a word or faltering for even a second, he walked straight through the explosion of water, which instantly drenched him. He continued walking through the cascading explosion, poems under his arm, straight down the sidewalk toward me, and home. It was as if he walked through Niagara Falls on a regular basis.

The summer of 1966 was a time of love and constant war news, a perpetual contradiction. I watched the news with one hand over my eyes. Screaming children, burning villages, and millions of peace signs, women crying in foreign languages, environmental destruction. Even on a black and white television, the news was in red. Anonymous art filled the streets with no concern for reviews. Art and theater were based on passion, rebellion, creativity, and dedication. Events of the world were the events of theater. The news and art were one and the same. In New York, the smell of pot lingered in subways, elevators, schoolyards and theaters. It was in office buildings, grocery stores, and all city parks. It was probably on hospital wards. The weeks were incomprehensible, complicated, and they were very long. It was not a normal decade.

At the beginning of 1966, there were approximately 200,000 American soldiers in Vietnam. By the end of the year there were over 400,000—nearly half a million. That summer, I rode with Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, in the latter’s Volkswagen van, to Ginsberg’s reading in Sundance, Pennsylvania. We left New York in Orlovsky’s van, and along the way Ginsberg asked me how often I read my poetry at readings. Whatever I answered, it wasn’t enough. He said that I had to read more. He said you can’t hear the poem on paper. If you want to understand it, you have to read it out loud. On paper isn’t enough.

For a man who was openly gay at a time of intolerance, and for a person who openly smoked marijuana at a time when the world wasn’t embracing the smoking of pot, and for someone openly and vehemently opposed to the Vietnam War, Ginsberg had an enormous innocence and bravery. That’s the way I saw him.

We stopped midway at a roadside stand in the middle of nowhere for something to eat. The menu probably consisted of three or four choices. Ginsberg and Orlovsky both professed to be vegetarians. I hadn’t made up my mind yet. Orlovsky ordered a cheese sandwich, I think, but then Ginsberg ordered a hot dog. I was shocked and ordered a hot dog myself. Ginsberg asked, “Are you sure that’s what you want?” I answered Yes, though I wanted to know what he was thinking. I didn’t question his behavior as I stood in a roadside stand with Ginsberg, the known vegetarian, the two of us chomping on hot dogs in the middle of nowhere.

We continued to Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and to a beautiful rambling farmhouse with a group of smaller guesthouses and an outdoor theater called Sundance, where Ginsberg gave his reading. The following day, people mingled, smoked, and skinny-dipped in a pool under trees. I didn’t swim then and still don’t, so I wandered around—fully clothed, then walked to the kitchen and made lemonade.

Ginsberg came into the kitchen, completely naked, sliced lemons, and proceeded to make lemonade. Orlovsky followed him into the kitchen, also completely unclothed. He gently and silently kissed Ginsberg’s naked behind as if it were the wing of a delicate butterfly, walked to the kitchen counter, and began to slice lemons for his own lemonade. I stood between them, fully dressed, with a tall glass of ice cubes, water, and lemon. Ginsberg returned to the group—some of whom were in the pool, others lounging under the trees. With iced lemonade in one hand and a manuscript in the other, he proceeded to read a poem to the listeners.

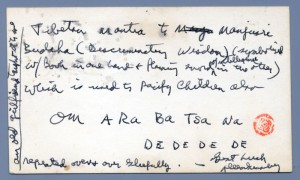

Three years later, in January, 1969, he would mail me a postcard. I was living in Newfoundland at the time, in a freezing, snow-covered town. He’d mailed the card from City Lights Bookstore. The tiny postcard traveled from City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco to a snow-covered house in western Newfoundland. He’d hand-written a lullaby on the card for my newborn daughter:

Three years later, in January, 1969, he would mail me a postcard. I was living in Newfoundland at the time, in a freezing, snow-covered town. He’d mailed the card from City Lights Bookstore. The tiny postcard traveled from City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco to a snow-covered house in western Newfoundland. He’d hand-written a lullaby on the card for my newborn daughter:

Tibetan mantra to Manjo Manjushri Buddha (Discriminating Wisdom) (symbolized w/ Book in one hand & flaming sword of intelligence in the other) which is used to pacify children also

OM ARA BA TSA NA

DE DE DE DE

repeated over and over gleefully.

An old girlfriend taught it to me

— Best Luck

Allen Ginsberg

And there was a small, orange Buddhist stamp pressed onto the card.

My childhood was, like most, a series of ups and downs. For two years, because of finances, we lived in the woods in an unheated cabin. During those years I got a ride into town and to school in the egg man’s delivery truck. I saw beautiful dawns in all kinds of weather, walked in the woods, and knew the features of spruce and fir, maple and pine. I watched the way light slid through branches and boughs, saw lacey patterns moving on earth, and heard the earth’s heart pounding in thunder as wind swirled around me. I was never afraid of it, not even the storms. Later, I marched and protested, and breathed in a new form of life at a magical underground theater called the Caffe Cino.

Memories gathered during the day need rest—they need sleep so they can keep house. They need a respite. We each carry a lifetime of memories around with us; we don’t leave them behind when we enter a room. They all travel with us. It may be good to release them at times, but not to abandon them.

Years ago, whenever I looked at clouds or tea leaves, I saw images. Now, whenever I look at anything, I see images. A moon being swallowed by clouds. White birds flying across the sun. High, crashing waves, sounds of wild birds and thunder. Moonbeams reaching into the sea. A tree, weathered and stooped, collapsed on an old picket fence, not caring what the neighbors think. Hot sun touching wild phlox and their perfume drenches a forest. A small town with a lilac tree on every road. The Empire State Building in red and silver and green, spruce trees on sidewalks and street corners smelling like forest. All the people we pass on the street only once in a lifetime. Fireworks lighting the sky over an anonymous town. Soup kitchens and hundreds of cups, hundreds of chairs, hundreds of glasses for juice—enough cranberry sauce for a thousand. Volunteers in aprons move with the precision of war. Any war. The large, bare room smells of home cooking and gravy. Squeak of a pulley, turning of ropes, an ominous sound—someone gathering laundry. The little streets we walked as a child and those little streets were the universe. People singing “O Holy Night” while the world is coming apart at the seams.

What exactly happened in my lifetime? I want to play that back slowly. It takes time to organize a life. If anyone tries to rush you, stand your ground: my advice to myself.

Magie Dominic, a Newfoundland- and New York-based writer and artist, is the author of the memoirs The Queen of Peace Room (2002) and its sequel Street Angel (2014). A new memoir titled Wherever I Look I See Images, the third in the trilogy, will be published later this year. Part of this essay was excerpted and adapted from a chapter in the forthcoming book.