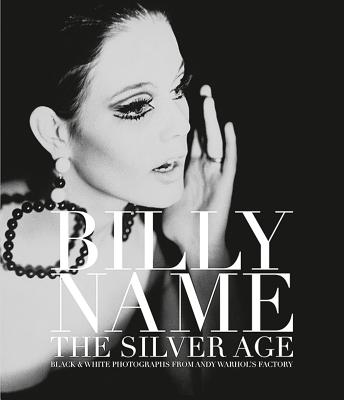

Billy Name: The Silver Age: Black and White Photographs from Andy Warhol’s Factory

Billy Name: The Silver Age: Black and White Photographs from Andy Warhol’s Factory

Edited by Dagon James

Reel Art Press. 448 pages, $75.

EVEN IF you don’t recognize the name, you are probably familiar with some of the images captured by photographer Billy Name. Certainly this is the case if you have even a passing interest in the phenomenon that was Andy Warhol. In fact, Name was briefly involved with Warhol romantically, but his more important and enduring role was as the official photographer of the Factory, Warhol’s famous studio in three Manhattan locations between 1962 and 1984, so named for the artist’s prolific output of paintings, silkscreens, and films.

Name took photos constantly from 1965 to 1970, when he lived in the Factory, which moved from its original location on East 47th Street to the Decker Building in Union Square in 1968. During this five-year period, Warhol created some of his most iconic paintings and films, including the highly experimental Chelsea Girls (released in 1968), which is still screened in film history classes everywhere.

The breadth of Name’s project is apparent in a new, epic collection of his photographs, Billy Name: The Silver Age. Name photographed everything and everyone, for the most part candidly, though there are a few posed compositions. This gives the book a powerful feeling of a documentary, of being in the moment with Warhol and his band of artists as they created their own countercultural universe. Interspersed with the photographs are quotations from various Factory members and artists, including Name himself, Warhol, actress Bibbe Hansen, poet–photographer–filmmaker Gerard Malanga, artist Brigid Berlin, and rocker Lou Reed.

Name’s contribution to the Factory doesn’t lie solely in his photographs. When Warhol first began to use the space to paint, there was no electric lighting. He would paint near a window and rely on natural light. It was Name who went to a shop and bought a bunch of lights and fixtures and then installed them. This is a telling anecdote, as one of the most striking features of Name’s work is his ability to contrast darkness and light. Indeed, this book should be a required text for photography students who want a better understanding of chiaroscuro, the Renaissance technique of highlighting the contrast between light and dark spaces.

Name was also responsible for one of the most memorable visual motifs of this rendition of the Factory. Warhol had covered the walls as completely as possible in aluminum foil. What he couldn’t cover in foil, Warhol explains, Name painted silver. “Why he loved silver so much I don’t know,” Warhol recalls. But “it was the perfect time to think silver. Silver was the future, it was spacey. The astronauts wore silver suits. … And silver was also the past—the silver screen, Hollywood actresses photographed in silver sets. Maybe more than anything, silver was narcissism.” Indeed the book’s subtitle dubs this era “the Silver Age.” It was all about surfaces, appearances, something Warhol himself understood very well.

Name was also responsible for one of the most memorable visual motifs of this rendition of the Factory. Warhol had covered the walls as completely as possible in aluminum foil. What he couldn’t cover in foil, Warhol explains, Name painted silver. “Why he loved silver so much I don’t know,” Warhol recalls. But “it was the perfect time to think silver. Silver was the future, it was spacey. The astronauts wore silver suits. … And silver was also the past—the silver screen, Hollywood actresses photographed in silver sets. Maybe more than anything, silver was narcissism.” Indeed the book’s subtitle dubs this era “the Silver Age.” It was all about surfaces, appearances, something Warhol himself understood very well.

Carefully edited by Dagon James, this collection of Name’s photographs confirms much of what we know about the zaniness of the Factory. If it challenges any of our conventional wisdom, it is the widely held image of Warhol as a self-obsessed, calculating asshole. This perception has come about from films like I Shot Andy Warhol, the 1996 film about Valerie Solanas, the woman who attempted to assassinate him, and documentaries such as 2010’s Beautiful Darling, which presented a rather unflattering portrait. As cited in the book, Bibbe Hansen, who began working with Warhol as a teenager, offers anecdotes that contradict this mythology. He was “quite generous,” she insists, adding that there is “too much cynicism” about Warhol, a mentor who granted artists great freedom to explore their creative potential.

At one point, Name describes the feeling of living at the epicenter of artistic creativity: “We were the top of the culture,” he says of the Factory, which had gained the notice of Bob Dylan, Tennessee Williams, and Judy Garland, among many others. “We could feel the power we had.” Looking at this remarkable collection of photographs, one gets a vivid sense of that power.

Editor’s Note: At press time we learned that Billy Name had died. His agent Dagon James issued the following statement: “Billy Name passed away peacefully in his sleep in New York on July 18 at the age of 76. I am devastated by the loss of my friend. He was a beautiful soul and a brilliant artist who touched countless people and helped shape the course of modern art and culture from the 1960s onwards.”

Matthew Hays is a Montreal-based writer who teaches film studies and journalism at Concordia University.