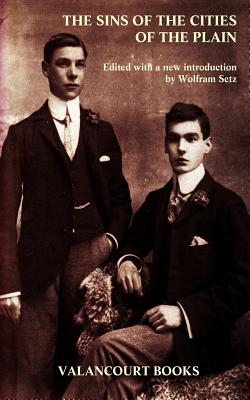

The Sins of the Cities of the Plain

The Sins of the Cities of the Plain

Edited by Wolfram Setz

Valancourt Books. 89 pages, $14.99

The Sins of Jack Saul: The True Story of Dublin Jack and the Cleveland Street Scandal (Second Edition) by Glenn Chandler

The Sins of Jack Saul: The True Story of Dublin Jack and the Cleveland Street Scandal (Second Edition) by Glenn Chandler

Grosvenor House. 312 pages, $15.99

AS EARLY AS 1964, Montgomery Hyde, in his book A History of Pornography, brought to our attention the first pornographic work in English to feature a male homosexual: The Sins of the Cities of the Plain, or The Recollections of a Mary-Ann, published anonymously in 1881. Oscar Wilde bought a copy at the end of the decade. But for 20th-century readers, the work remained unavailable.

In 1992, Masquerade Books included the title as part of their Badboy series. It was not until Valancourt brought out its edition in 2012 that the majority of us learned of the deception Badboy had sprung on readers. The original contains several heterosexual scenes; Badboy made them all homosexual. Though the original is sexually explicit, it was not enough for the Badboy editor; he added gobs of newly created material. A number of scholars admonished readers that the text was corrupt, but one would have had to stumble upon their warnings to know. The authentic Valancourt text arguably has no greater literary value than the Badboy travesty, but now, at least, the work’s cultural significance is secure.

Sins of the Cities presents the first history of a male prostitute as told from his own viewpoint—and without apology. Its main character is Jack Saul, whose life is written up from “his rough notes” commissioned by a certain “Mr Cambon.” The two men first meet in November 1880, when Cambon cruises Saul in Leicester Square, being attracted by the “extraordinary” size of the “lump in his trousers.” He is equally struck by Saul’s expertise at oral sex and asks for an account of how he arrived at such proficiency. Saul agrees to provide a narration of his life, with the understanding that he will be paid for his efforts. Saul is thus frequently cited as the “author” of the resulting book. If so, he must share the title with Cambon. The latter’s introduction takes up seven-and-a-half pages in the Valancourt edition. His voice returns for eight pages at the end of the book in three essays apparently designed as filler to reach the requisite length.