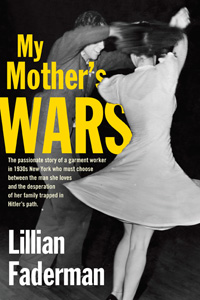

My Mother’s Wars

My Mother’s Wars

By Lillian Faderman

Beacon Press. 288 pages, $25.95

LILLIAN FADERMAN is probably best known for coining the term “romantic friendship” for the kind of intense but usually nonsexual relationship between women that was socially acceptable before the spread of Freudian thought. Her book on this subject, Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present (1981), has become a classic feminist text. Faderman’s explorations of lesbian history have continued since then.

More recently, Faderman has turned away from history as a scholarly pursuit so as to explore her personal history. Her autobiographical book Naked in the Promised Land came out in 2003. Now she has followed up with My Mother’s Wars, the story of her Latvian-Jewish mother’s immigration to New York in 1914 and her life there until Lillian’s birth in 1940.

This book is a remarkable work of reconstruction. It begins with the “American dream” of Mereleh Luft, a teenage girl in Latvia: “She’d been sent out to be an apprentice, first to a milliner and then to a dressmaker, and with loathing she’d believed the needle would be her whole life. Then one of the girls with whom she’d worked at the dressmaker’s told her about a sister who’d gone to New York and was already an actress on the Yiddish stage and getting paid good money for it. That was when Mereleh began to dream. Why not? She’d danced at the Purim festivals in Rezhitse for several years, and every single time, the other dancers stopped to watch her and applaud.”

Remarkably, Mereleh persuaded her working-class parents to let her travel, by horse-drawn carriage, train, and ship, to New York to live with Sarah, an older half-sister she barely knew, and Sarah’s husband. Faderman speculates that perhaps Mereleh’s parents wanted to give their daughter opportunities that they never had and to escape the anti-Semitism that was already threatening their community, a situation that limited young people’s life choices.

The life and times of “Mary Lifton,” as Mereleh called herself in New York, are colorfully described  in a series of chapters that begin with news clips labeled “Time on the March,” like those shown in movie theaters at the time. As Mary remains trapped in low-paying jobs in the garment industry, the United States sinks into the Great Depression and Hitler rises to power in Europe. Mary never forgets her promise to her younger brother Hirschel that she would bring the rest of the family to join her, starting with him.

in a series of chapters that begin with news clips labeled “Time on the March,” like those shown in movie theaters at the time. As Mary remains trapped in low-paying jobs in the garment industry, the United States sinks into the Great Depression and Hitler rises to power in Europe. Mary never forgets her promise to her younger brother Hirschel that she would bring the rest of the family to join her, starting with him.

Mary’s fear for her relatives as things get worse on both sides of the Atlantic, and her bursts of false hope, create an air of suspense in her life story, even though the reader knows only too well what eventually happened to the Jewish population of Europe. News items about anti-Semitism in the U.S. and negative American attitudes toward foreign immigrants in hard economic times provide a grim counterpoint to the news from Europe.

Mary’s affair with a charming younger man, Morris Federman, is presented as both comic and tragic. Year after year, she hopes he will marry her despite his mother’s disapproval and his own American dream of success as a businessman or an outlaw. Like a scriptwriter, the author does a brave and fairly convincing job of describing their dates, their clothing, their conversations, and the political gap between Morris the anti-Communist and Mary the proud union member. Faderman even evokes the enduring sexual attraction that kept drawing her parents together, despite their differences.

The life story ends with the author’s birth and is followed by a voluminous list of resources. As usual, Faderman’s seemingly effortless prose is the result of years of patient research. As far as possible, she has made sure that the past will be accurately remembered. One motive in writing this biography is revealed by the book’s dedication: “To my son Avrom: Here is your grandmother.”

Jean Roberta teaches English in a university in Saskatchewan, Canada, and writes in several genres.