I THINK I saw nine feature films at this year’s Provincetown International Film Festival in June—and an excellent crop of flicks it was. This is not a gay-themed festival, but—it being P’town—a healthy proportion (a third?) of the films on offer had an LGBT theme. Here are four that I’d like to bring to your attention. (Note: There are so many production companies involved in each, I’ve given up trying to list them all.)

Richard Schneider Jr.

God’s Own Country

God’s Own Country

Directed by Francis Lee

The Yorkshire dialect is so thick that I understood about half of the dialogue (subtitles would have helped); but it didn’t matter. There wasn’t much of it anyway, as this is a film about two taciturn young men who have a job to do, birthing ewes, mending stone walls, making camp together at night. Inevitably, God’s Own Country has been compared to Brokeback Mountain, another film about two manly men engaged in physical labor far from the madding crowd. In the English version, Johnny and George are sheep farmers, the former the farm owner’s son, the latter a Romanian man who’s come to help during birthing season while escaping a homeland that’s “dead.” (The film appears to be set in the recent past—no computers or cell phones, but this is rural England, so it’s hard to say.)

The two men show no outward signs of “gayness” and seem to have few reference points for connecting it to themselves; they call each other “faggot” once their shared secret is out. We would call this “internalized homophobia,” but for them it seems to be the only word they have for themselves, uttered with an embarrassed grin. As in Brokeback Mountain, the men fall in love in spite of themselves, resisting their feelings for as long as they can, so their love is of that authentic, primal kind that makes its own rules when it finally breaks free.

The two men show no outward signs of “gayness” and seem to have few reference points for connecting it to themselves; they call each other “faggot” once their shared secret is out. We would call this “internalized homophobia,” but for them it seems to be the only word they have for themselves, uttered with an embarrassed grin. As in Brokeback Mountain, the men fall in love in spite of themselves, resisting their feelings for as long as they can, so their love is of that authentic, primal kind that makes its own rules when it finally breaks free.

Tom of Finland

Tom of Finland

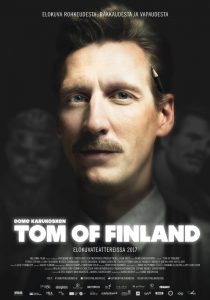

Directed by Dome Karukoski

From a formal standpoint, this movie follows the formula of your basic biopic—but, hey, it’s a biopic about Tom of Finland (1920–1991), so it’s bound to be offbeat. Most readers of this magazine scarcely need reminding that Tom of Finland was the artist who created those exaggerated drawings of big happy boys doing the nasty in every conceivable position, wearing leather accouterments or nothing at all. The film spans the artist’s entire adult life, with actor Pekka Strang aging convincingly from the young Touko Laaksonen serving as a Finnish officer in World War II to his final years, when he was celebrated at conventions of “Tom’s Men” in the U.S. We learn that his interest in drawing men in leather began early on, fueled by wartime sightings of soldiers on or off motorcycles, though he survived as a successful commercial artist after the war.

The film presents Laaksonen—“Tom” came much later, an American PR invention—as a cool customer who narrowly escapes detention in Germany when his passport is stolen by a trick. He keeps drawing those naughty pictures even when the risks heat up, eventually sending a few to a gay magazine in L.A., and the rest is history. His mild-mannered demeanor—interrupted by outbursts of guilt or anger over crimes witnessed or committed during the war—contrasts sharply with the wide-eyed, uncomplicated boys who appear in his work. It would be easy to assume that they provided a fantasy world into which a troubled artist could escape, but Laaksonen is depicted as a shrewd businessman who found a winning formula for success.

The film presents Laaksonen—“Tom” came much later, an American PR invention—as a cool customer who narrowly escapes detention in Germany when his passport is stolen by a trick. He keeps drawing those naughty pictures even when the risks heat up, eventually sending a few to a gay magazine in L.A., and the rest is history. His mild-mannered demeanor—interrupted by outbursts of guilt or anger over crimes witnessed or committed during the war—contrasts sharply with the wide-eyed, uncomplicated boys who appear in his work. It would be easy to assume that they provided a fantasy world into which a troubled artist could escape, but Laaksonen is depicted as a shrewd businessman who found a winning formula for success.

After Louie

After Louie

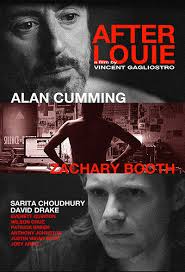

Directed by Vincent Gagliostro

Alan Cumming stars as a New York artist named Sam Cooper who once had a successful career but stopped painting at some point and today is working on a video project about the life and death, by AIDS, of a close friend back in the ’90s. The plot becomes a contest between two generations when Sam meets Braeden, a man in his late twenties who comes on to Sam, who in turn assumes that Braeden must be a hustler. As fascinated as Sam is by his handsome new friend, his bitterness about the past is  only sharpened by Braeden’s blasé attitude toward being gay and his ignorance of past struggles. Sam later denounces a couple of gay friends for getting married, i.e. succumbing to bourgeois respectability. The generational clash is underscored via a device whereby grainy scenes of Sam from the ’80s appear intermittently, amateur footage presumably filmed by friends. The direction has a makeshift feel, as if the director would set up a scene and say, “Now get out there and act!” This lends itself to a natural flow of dialog in a movie that drifts along, pleasantly enough, to no particular conclusion.

only sharpened by Braeden’s blasé attitude toward being gay and his ignorance of past struggles. Sam later denounces a couple of gay friends for getting married, i.e. succumbing to bourgeois respectability. The generational clash is underscored via a device whereby grainy scenes of Sam from the ’80s appear intermittently, amateur footage presumably filmed by friends. The direction has a makeshift feel, as if the director would set up a scene and say, “Now get out there and act!” This lends itself to a natural flow of dialog in a movie that drifts along, pleasantly enough, to no particular conclusion.

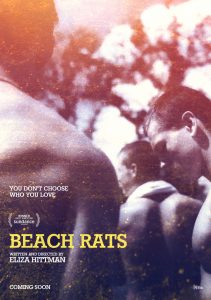

Beach Rats

Beach Rats

Directed by Eliza Hittman

Billed as a coming-of-age story—though one might question this claim—Beach Rats is about a working-class kid in Brooklyn who hangs out with a trio of thuggish friends and does drugs while struggling with being gay (he spends a lot of time on a Manhunt-like website). Frankie is super-easy on the eyes, and he’s almost never out of our sight. The only time we’re not looking at Frankie is when we’re seeing the world from his point of view, as when he’s high on uppers and pot at a loud outdoor dance party trying to impress both his posse and his girlfriend, and the world is spinning out of control. Did I mention that he has a girlfriend? Like many closeted young men in his situation, he goes out of his way to be seen in public with a female companion, even while desperately trying to avoid a private encounter with her that might end in failure.

The boys drift through summer, hanging out at the beach and at penny arcades until they start to run low on money and drugs—a predictable prelude to the end of innocence. Frankie’s penchant for hooking up with guys he meets on-line converges with his need for weed in a particularly sinister way. (Annoyingly, the film implies that marijuana is the kind of drug that people steal and kill for.) As Frankie descends deeper into survival mode, a question arises: will he perform a single decent act that could prove he’s a human being, or reveal himself to be a monster at root? The answer, alas—spoiler alert—is sure to disappoint.

The boys drift through summer, hanging out at the beach and at penny arcades until they start to run low on money and drugs—a predictable prelude to the end of innocence. Frankie’s penchant for hooking up with guys he meets on-line converges with his need for weed in a particularly sinister way. (Annoyingly, the film implies that marijuana is the kind of drug that people steal and kill for.) As Frankie descends deeper into survival mode, a question arises: will he perform a single decent act that could prove he’s a human being, or reveal himself to be a monster at root? The answer, alas—spoiler alert—is sure to disappoint.