ARLEZ-VOUS ALLEMAND?” In the early 1900s, this question (“Do you speak German?”) could be heard in certain pissoirs and cruising spots around Paris, a coded way to ask if someone was gay. This expression derived from the fact that same-sex sexuality was starting to be called “the German vice” at this time, and Berlin was seen as the destination of choice for such activities.

Charges of homosexuality in the government and in the military were taken very seriously in Wilhelm II’s Germany (1890–1918). There had been some scandals involving the German Army and the apparent suicide, in 1902, of industrialist Friedrich Alfred Krupp after proof of his dalliance with boys on the Isle of Capri became public. But it was the so-called Eulenburg Affair that truly shocked Germany and the world, and that had the more serious consequences. A group of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s closest friends and cabinet members were brought to trial on charges of homosexuality in a series of five civil trials and court-martials lasting from 1907 to 1909. In the course of the highly publicized proceedings, at which the renowned sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld testified, concepts of homosexuality and gay identity would become issues of public discussion for the first time. It could be argued that the modern concept of gay identity was born during the Eulenburg Affair. (Two recent books, Robert Beach’s Gay Berlin (2014) and Martin Duberman’s Jews Queers Germans (2017), discuss the affair and acknowledge its importance.)

The general public in both Germany and France viewed homosexuality as a perversion, and men who engaged in it were seen not only as effete, but also, because they were vulnerable to blackmail, as a potential threat to national security. No doubt this is part of the reason why the French, Germany’s chief enemy, spoke of “the German vice” and depicted German military personnel on postcards as unmanly and effeminate. And while feminizing one’s enemy was standard practice, French postcards were particularly profuse and imaginative in doing so. Similar sentiments, interestingly, can be found on Polish, Italian, and Belgian cards, while Germans themselves at times gave a humorous twist to their being associated with homosexuality.

So, let me share some of my findings regarding this important episode in queer history as it is reflected on postcards, which were an early medium by which ordinary people could learn about current events and be exposed to new ideas. Indeed, the importance of postcards cannot be overstated. During their golden age, from 1898 to 1919, billions of cards were printed and exchanged throughout the world. In 1909 alone, the last year of the Eulenburg trials, an estimated 833 million cards were mailed in Great Britain, 668 million in the U.S., 160 million in Germany, and eighteen million in France.

Figure 1. In “The Moltke-Harden Trial,” Count Kuno von Moltke is shown leaving the courthouse where his libel case is being heard against Maximilian Harden, editor of the news magazine Die Zukunft. Harden had accused Moltke, the recently resigned military commander of Berlin and member of the Kaiser’s inner circle, of being homosexual, and Moltke sued. Testimony revealed that Moltke was in a sham marriage with his wife, Lilly von Elbe, who blamed her husband’s infatuation with Prince Philipp zu Eulenburg for the marriage’s failure. Eulenburg, an intimate friend of the Kaiser’s, was a prince and hereditary peer in the Prussian House of Lords and had served as ambassador to Austria-Hungary before being exposed as homosexual. In the end, Moltke, with his somewhat effeminate mannerisms, was judged “subconsciously homosexual,” a position argued by Magnus Hirschfeld, while Harden was acquitted. At no point was Moltke accused of violating paragraph 175 of the German penal code, which criminalized homosexual acts. Over fifty foreign journalists were assigned to cover the series of trials, and hundreds of articles covering the events were published. On the second day of the first trial, police were called in to control the crowds outside.

Figure 2. A humorous spoof on the Eulenburg affair can be found on a German card featuring a fairy tale maiden and two couples. The central couple is comprised of two men in an embrace. The one on the left is pictured as effeminate, dressed in a checkered suit and with his derrière protruding. The men cry out to one another: “My Sweetie! You, my beloved soul!” To their right is an ordinary-looking older couple in which the frau admonishes her husband: “Look, old guy, you never flatter me with such pretty names.” On the left side is an inset showing a long-haired young princess with a castle tower behind and a caption that reads “Phili: Fairy Tale.” This is a reference to Prince Eulenburg (“Phili”), and the terms “sweetie” and “my beloved soul” came up in the libel trials as terms of endearment exchanged between Moltke and his alleged lover Eulenburg.

Figure 2. A humorous spoof on the Eulenburg affair can be found on a German card featuring a fairy tale maiden and two couples. The central couple is comprised of two men in an embrace. The one on the left is pictured as effeminate, dressed in a checkered suit and with his derrière protruding. The men cry out to one another: “My Sweetie! You, my beloved soul!” To their right is an ordinary-looking older couple in which the frau admonishes her husband: “Look, old guy, you never flatter me with such pretty names.” On the left side is an inset showing a long-haired young princess with a castle tower behind and a caption that reads “Phili: Fairy Tale.” This is a reference to Prince Eulenburg (“Phili”), and the terms “sweetie” and “my beloved soul” came up in the libel trials as terms of endearment exchanged between Moltke and his alleged lover Eulenburg.

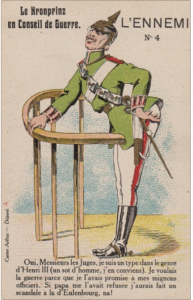

Figure 3. The association of Prince Eulenburg with the homosexuality believed to be rampant throughout Germany and its military prevailed for many years after the trials of 1907–1909. On a French propaganda postcard mailed in 1920, an effeminate Crown Prince Wilhelm testifies in court. “Yes, Your Honors, I am the same type of person as Henry III (a fool of a man, I agree). I wanted the war because I had promised it to my darling officers. If my father had refused, I would have caused a scandal à la Eulenburg, you understand?” Henry III was a 16th-century king of France who was said to have had homosexual relations with his court favorites, known as the “mignons,” the same word used by the crown prince to describe his officers. Wilhelm stands with his rear end sticking out while his monocle and bright red lips further indicate effeminacy. The card, titled “The Crown Prince at the Council of War,” is number 4 in a series called “The Enemy.” A decade after the trial, the assumption is being made that recipients of this French card would still remember the Eulenburg scandal.

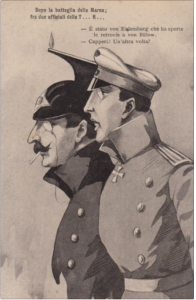

Figure 4. An undated Italian card referring to the Battle of the Marne in World War I again evokes the name of Eulenburg to refer to homosexual behavior. On the card, two officers after the battle are having the following dialogue: “First officer: It was von Eulenburg who opened the rear to von Bülow. Second officer: Golly! Once again?” Von Bülow was the German ambassador to Italy from 1914 to ’15 and was unable to persuade Italy to join the Central Powers. Earlier he had been accused by the journalist Maximilian Harden of homosexual behavior at the all-male social gatherings of the Kaiser’s friends hosted by Prince Eulenburg.

Figure 4. An undated Italian card referring to the Battle of the Marne in World War I again evokes the name of Eulenburg to refer to homosexual behavior. On the card, two officers after the battle are having the following dialogue: “First officer: It was von Eulenburg who opened the rear to von Bülow. Second officer: Golly! Once again?” Von Bülow was the German ambassador to Italy from 1914 to ’15 and was unable to persuade Italy to join the Central Powers. Earlier he had been accused by the journalist Maximilian Harden of homosexual behavior at the all-male social gatherings of the Kaiser’s friends hosted by Prince Eulenburg.

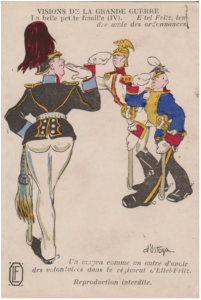

Figure 5. Kaiser Wilhelm’s second son Eitel Friedrich, though married, was rumored to be gay. Like his older brother Wilhelm, he also fought in World War I. A French postcard hints at Eitel’s illicit relations with his orderlies, while depicting him in the most unflattering (for a soldier) manner. The top of the card reads: “Visions of the Great War. The pretty little family. Eitel Fritz, sweet friend of the orderlies.” Below the caricature, the caption reads: “One of the ways of getting volunteers into Eitel Fritz’ regiment.” Eitel is shown from the rear with protruding buttocks, standing daintily with one foot in front of the other. With a white-gloved hand to his puckered lips, he is returning a salute to two other servicemen. The card is signed by the artist, Jerzy Ostoja (1878–1937).

Figure 6. A scathing allusion to Moltke can be found on another French propaganda card from World War I. This card, mailed in 1914, depicts a French soldier with his bayonet penetrating the rear of a German soldier, who is throwing up his arms in pain. The French caption above the illustration reads “War 1914,” and the one below reads “Sheaths for French bayonets patented by Moltke.” Feminizing the enemy is standard practice in war propaganda, but this explicitly sexual image recalls the accusations related to Moltke’s homosexual liaisons from a decade earlier.

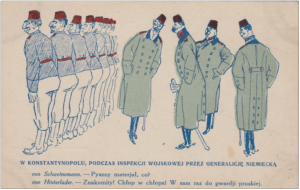

Figure 7. The theme of rampant homosexuality in the German military extends to an illustrated postcard printed in Poland. Here, four German officers are assiduously inspecting a group of Turkish soldiers from behind, focusing on their butts. The main caption reads: “In Constantinople, during a military inspection by a body of German generals.” Under that, a soldier named von Schweinemann is saying: “Delicious material, no?” Another, von Hinterlader, replies: “Outstanding! Chap for chap! Perfect for the Prussian guard!” The name Schweinemann translates as “Pig Man,” while Hinterlader, which literally means “breach-loading gun,” was a vulgar term for a homosexual.

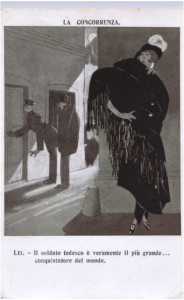

Figure 8. German soldiers were known at times to prostitute themselves, if only to earn a bit of extra income, and there were areas of Berlin where one could make such connections. On an Italian postcard titled “Competition,” a female prostitute looks on resentfully from behind a wall at two men about to enter a building. The man bending over in front to open the door is a German soldier. Directly behind, if not pressed against his protruding rear end, is a finely dressed gentleman in a top hat. The caption reads: “She: The German soldier is really the greatest conqueror in the world.”

Figure 8. German soldiers were known at times to prostitute themselves, if only to earn a bit of extra income, and there were areas of Berlin where one could make such connections. On an Italian postcard titled “Competition,” a female prostitute looks on resentfully from behind a wall at two men about to enter a building. The man bending over in front to open the door is a German soldier. Directly behind, if not pressed against his protruding rear end, is a finely dressed gentleman in a top hat. The caption reads: “She: The German soldier is really the greatest conqueror in the world.”

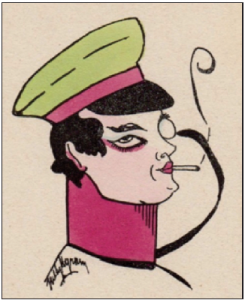

Figure 9. During the Eulenburg trials, questions arose as to the nature of  male homosexuality. Was it inborn, as many thought, indicative of a “third sex,” or acquired? Or was it simply one variant in the array of sexual feelings and behavior exhibited by men? Due largely to the public discussions generated by the trials, the word “homosexual” signifying a personality type started to gain currency. On an anti-German card, printed in Brussels, we see in profile the head of a German officer, made to look effeminate with his eye liner, monocle, and reddened lips. Below are the words “Une ‘tante’ d’Allemagne!,” best translated as “a German auntie.” It is an early example of a postcard revealing how society was coming to view homosexuals as a social type.

male homosexuality. Was it inborn, as many thought, indicative of a “third sex,” or acquired? Or was it simply one variant in the array of sexual feelings and behavior exhibited by men? Due largely to the public discussions generated by the trials, the word “homosexual” signifying a personality type started to gain currency. On an anti-German card, printed in Brussels, we see in profile the head of a German officer, made to look effeminate with his eye liner, monocle, and reddened lips. Below are the words “Une ‘tante’ d’Allemagne!,” best translated as “a German auntie.” It is an early example of a postcard revealing how society was coming to view homosexuals as a social type.

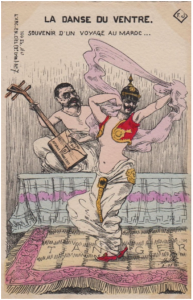

Figure 10. A rather curious French card labeled “The Belly Dance: souvenir of a voyage to Morocco” refers to Kaiser Wilhelm’s visit to Tangier in 1905. The Kaiser declared that he had come to support the independence of Morocco, a stance that was a direct challenge to French influence in the country. The French card implies that the only return for Germany was a belly dancer in the form of a German soldier performing a sexy dance with a veil. Rather ironically, three years later, while performing a pas seul in a tutu in the presence of the Kaiser at a private estate, chief of the Military Secretariat Dietrich von Hülsen-Haeseler dropped dead. The affair, with its homosexual overtones, was hushed up at the time.

Figure 10. A rather curious French card labeled “The Belly Dance: souvenir of a voyage to Morocco” refers to Kaiser Wilhelm’s visit to Tangier in 1905. The Kaiser declared that he had come to support the independence of Morocco, a stance that was a direct challenge to French influence in the country. The French card implies that the only return for Germany was a belly dancer in the form of a German soldier performing a sexy dance with a veil. Rather ironically, three years later, while performing a pas seul in a tutu in the presence of the Kaiser at a private estate, chief of the Military Secretariat Dietrich von Hülsen-Haeseler dropped dead. The affair, with its homosexual overtones, was hushed up at the time.

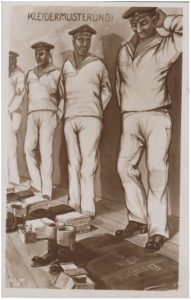

Figure 11. Germans were not without a sense of humor when it came to homosexuality. On a card titled “Kleidermusterung!” (“clothing inspection”), two sailors in a line waiting to be inspected break rank. The one furthest to the right assumes a feminine pose of modesty with his eyes cast downward and his left arm held coyly behind his head. The adjacent sailor glances over with desire. Here, the image of the male sailor, long an icon of heterosexual virility, takes on a new twist.

Figure 11. Germans were not without a sense of humor when it came to homosexuality. On a card titled “Kleidermusterung!” (“clothing inspection”), two sailors in a line waiting to be inspected break rank. The one furthest to the right assumes a feminine pose of modesty with his eyes cast downward and his left arm held coyly behind his head. The adjacent sailor glances over with desire. Here, the image of the male sailor, long an icon of heterosexual virility, takes on a new twist.

The first quarter of the 20th century witnessed a heightened interest in homosexual behavior in Germany, spurred on by high- profile government scandals and concerns for state security. The Eulenburg Affair of 1907–1909 set the stage for open public discourse on the nature of homosexuality while at the same time drawing all the more attention to Germany as a center of homosexuality and confirming the notion of “the German vice.” This association of Germany with homosexuality was then employed for propagandistic purposes by Germany’s enemies in World War I. The picture postcard, a ubiquitous means of communication at the time, both reflected and reinforced this stereotype.

Stephan Likosky’s latest book is With a Weapon and a Grin: Postcard Images of France’s Black African Colonial Troops in WWI (2017).