IT’S A BUSY FRIDAY NIGHT at the Cocoon, the main gay club in Krakow, one of the largest clubs in Poland. The former cinema is full of bodies: male, female, and in-between. Young men dance ferociously, disappearing from time to time into the sweat of the dark room. Someone points out that the man standing next to the wall, surrounded by adoring men, is the newly elected Mr. Gay of Poland.

Is the “cocoon” an apt metaphor for gay life in the officially Catholic country, another word for “the closet”? Or would a better metaphor be, as some have suggested, that of a nest that breeds sin and a new erotic capitalism, as Poland prepares to join the European Union (EU)? Poland is a special case here since it is the most sexually conservative country among former Soviet satellites. The political revolution happened here, but not the sexual one. Is it happening now?

The state of human rights for sexual minorities can serve as a lens through which to observe the condition of Polish democracy as it has entered society and culture since the fall of Communism in 1989. Like democracy itself, the evolution of gay rights is far less advanced in Poland than in Western Europe. At the same time, victimhood is no longer an acceptable option for the growing gay and lesbian movement in today’s Poland. The civil right activities that started in the 1980’s and the demands for equal rights and visibility in public space have become stronger with each passing year. The Polish Gay Pride Parade has been organized in Warsaw since 1995, and the first Mr. Gay contest took place in 1997.

While human rights in relation to sexual orientation may lag in Poland and Eastern Europe generally, there is for that very reason a transforming energy contained in sexual otherness that makes the subject here different from its Western incarnation. The commercial commodification has not quite happened yet, and the political and social implications of being gay are still at the cutting edge. Moreover, for a country like Poland that’s struggling with both democracy and religious fundamentalism, the problem of sexual difference can give art a margin for subversiveness and even revolutionary potential.

This transforming energy is present in the works that visual artists have produced during this period. Let me offer the possibility that visual culture can operate as an agent for change in a society in which sexual minorities form a political underclass. In my quest to capture the transformation that has occurred since 1989, then, I have examined the homosexual motifs in the art of the 1990’s.

Coming Out in Public Art

In 1992 the office of the Director of the Provincial Center Of Culture, located in the City Hall in Gdansk, was magically transformed for three days when its interior was covered with a snow-white mist of down. The installation by Krzysztof Malec, a young artist, was entitled Silence; it altered the institutional space and exposed to the public an alternative version of the office. The filling of the room with a weightless down effaced the room’s material shapes and sharp edges, and created an atmosphere of secrecy and otherness. Among the many associations that this installation evoked, its title, “Silence,” offers the best clue to its central meaning: that of an unspoken presence in the official architecture, mute but all-encompassing, altering reality yet leaving it exactly the same.

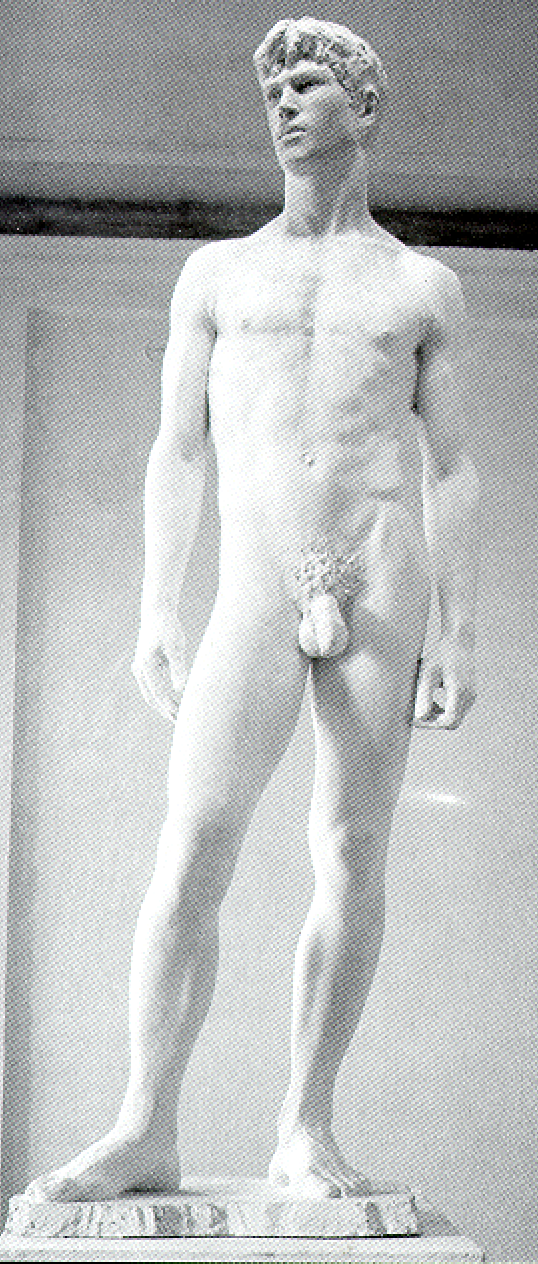

Three years later, the artist took the next big step, offering a much more direct expression with a sculpture, The Male Nude, in an exhibition called “I and AIDS,” organized by artists in 1995 in Warsaw’s Capital Cinema. It was the first art show devoted to AIDS to be held in Poland. The exhibition was censored after two days as too controversial. In addition to their sexual content, many works depicted the human body in contexts of threat, surveillance, and fear. At the center of the show stood Krzysztof Malec’s The Male Nude, a white plaster sculpture of a muscular subject. The artist’s earlier “silence” has now become an explicit statement: a fully embodied erotic desire. The Male Nude clearly refers to Michelangelo’s David, an emblem of homosexual desire in art.

The shift from the highly metaphorical Silence to The Male Nude’s explicitness marks a transition in Polish society and culture in the 1990’s. The “silence” of the earlier work reflects one side of the question of gay and lesbian identity in contemporary Polish life. In the realm of politics and law, the subject of homosexuality is hardly visible or else is treated with disdain. But in the realm of popular culture, the media and its consumerism tell another story. The sexual otherness is an attractive product to sell, in a limited dose, of course, especially in a form of talk-show trauma, comedy, or erotic tease.

But the Polish gay and lesbian associations (Lambda, Campaign Against Homophobia, and ILGCN Poland) are working on legal changes, on improvement at the level of official policies of the state towards sexual minorities. At stake are such key issues as passing a law against discrimination, introducing partnership agreements, and initiating anti-homophobic education in schools. Throughout the 90’s there was little official discussion of these matters. Hence, the down of silence filled the office in a public institution associated with power. Malec’s installation was thus a kind of secret intervention that stole its way into an official space that was closed to homosexual rights.

And it’s a space that remains oblivious or hostile to these rights to this day. Actually, homosexuality was decriminalized in Polish law in 1932, very early compared to Western European societies, which didn’t do so until the 1960’s and 70’s. Formally, the surprisingly liberal law continued to function in Communist Poland after World War II. But the law did little to change the negative attitudes of society and the authorities. Under Communism homosexuality tended to be viewed as a social pathology or psychological disorder, and it shows up in mostly medical and criminal contexts. This attitude continues to operate in Polish society today—polls continue to show that seventy to eighty percent of Poles dislike homosexuals—and the recent Constitution is a continuation of it.

The Constitution of 2 April, 1997, lays out in Article 32 the fundamental principle of non-discrimination “on any grounds.” This phrase is the result of a compromise reached in the debate preceding the adoption of the Constitution. One of the drafts specified “sexual orientation” as a protected category, but this draft was strongly opposed by the Catholic Church and by president Lech Walesa, who stated that this inclusion could be a danger for the family and the moral upbringing of children. This draft was finally rejected in favor of a provision that barred discrimination “on any grounds.”

The Public Body and the Body Politic

A second city hall event involved a “public projection” of words and images by artist Krzysztof Wodiczko at the City Hall Tower in Krakow in August 1996. Wodiczko is an international champion of critical public art. He uses a technique of public projection onto the walls of buildings associated with power. In his art he undertakes a study of otherness and alienation, which he calls “xenology.” The Krakow action was an instance of xenology in which he projected the alienation of a gay man in a newly democratic Poland that remains inhospitable to sexual minorities.

It was a dark rainy evening. The artist projected images of hands holding various objects, as if attributes of human fate, on the brick wall of the City Hall Tower in the center of Market Square. The images of hands were accompanied by voices resonating across the square. One told the story of an abused wife, another of the lonely, fear-filled life of a drug addict. Another image depicted the gesticulating hands of a young gay man. The voice that went with them told his story of the physical pain of being beaten, and the spiritual pain of rejection.

In Wodiczko’s view, a public projection can change the lives of the marginalized. His art takes them from a space of invisibility at society’s outer edges, of non-being, and thrusts them into center stage. Now it becomes apparent that they’re victims of society—of violence and intolerance that have caused them to seek refuge at the margins of society. By projecting these images onto the symbol of official power, Wodiczko has produced not only a monument to society’s “losers” but also a kind of negative monument to society’s inhumanity in its treatment of some of its members.

Soon after this action the national campaign for the victims of domestic violence started, but nothing has changed in the situation for sexual minorities. This suggests that Wodiczko’s approach is not without drawbacks. By projecting the Other as essentially a victim, the artist may succeed in making people feel compassion for the outsider’s suffering—but that places them in a position of superiority vis-à-vis the victim, and not one of equality.

The “I and AIDS” exhibition was not only Krzysztof Malec’s moment; it was also the event at which Andrzej Karas, the first openly gay artist in Poland, appeared on the scene. His coming out was staged as an artistic performance. In a series of three collages set in fetishistic frames of red plush, the artist placed his own likeness in the middle of cut-outs from erotic gay magazines. Fragments of exposed masculine bodies overlap, creating a whirlpool of desires, a performance exploding with lust. Inside this visual-libidinal confection, in the center of this picturesque orgy, reigns an image of the artist masked in pagan costume. Through this mosaic of organs and muscles, in effect, the viewer enters the artist’s own auto-erotic dream.

The works of Andrzej Karas are based upon self-portraits in which a desire for artistic expression is combined with a personal longing to reveal one’s sexuality and one’s physical self. His art confronts the outside society’s demand for concealment of desire and the gay world’s very different standards of sexual expression. The latter is the subject of Karas’s most interesting works, many of which are often inspired by pornography. These self-portraits depicting his erotic fantasies signal the arrival of a self-aware and open homosexual creativity in Polish visual culture. To be sure, such art has not entered the broad public consciousness of Poland, but its appearance reveals a freedom of expression for the new generation of artists and their audience.

Women’s Art

Many of the most intriguing works concerned with homosexual eroticism in Poland are being created by women. Women artists use their work to critique the patriarchal scheme of gender relations and to explore the potentialities of sex. Katarzyna Kozyra’s video installation, which represented Poland at the Venice Biennale in 1999 and won a prize of distinction there, was built on video clips taken at a men’s bathhouse. Kozyra, disguised as a man with a false beard and a penis, clandestinely shot the footage of men in the Gellert Bathhouse in Budapest, a venue for gay cruising and casual sex.

The Men’s Bathhouse is realized from a gay man’s point of view. The artist introduces the viewer as one of the participants in an interplay of desiring gazes. In her narrative the artist discusses the homosexual atmosphere and incessant interplay of erotic looks—as well as her embarrassment over trying to participate while disguised as a man. In a fascinating way this embarrassment passes on also to viewers of her art, especially to the male part of the audience. Kozyra strongly sexualizes the male body through both the feminine and the gay male gaze.

The paradox of invisibility and visibility appears here again: an ambiguity that goes to the core of current attitude towards homosexuality. In 1999, Poland was awarded one of her few prizes at the Venice Biennale, the most prestigious European exposition of contemporary art, for a video installation about a gay meeting place. The Biennale is a strongly nationalist show in that the art is chosen to represent the country of origin, with Kozyra’s installation representing Polish culture that year. This fact would seem to be a testament to the liberalization of Polish culture—yet the very success of Kozyra’s showing triggered a campaign against contemporary art in Poland and a return to censorship (especially in the cases of merging the religious and the erotic). In like fashion, as soon as The Men’s Bathhouse appeared, many Polish authorities blasted the work despite its acclaim on the international scene.

Still, Karas’s self-portraits and Kozyra’s Bathhouse signal a fundamental cultural change in sexuality that’s taking place in Poland and is probably not stoppable, for all the sad reality of official resistance as depicted in Krzysztof Wodiczko’s works. Meanwhile, the Polish gay organization Campaign Against Homophobia plans another action of public art entitled “Let them see us” for later this year. Billboards for the show are supposed to depict photographic portraits of gay and lesbian couples holding hands right in the middle of Poland’s major cities.

IN THE TRADITION of Malec’s The Male Nude, gay art has focused on the beauty and eroticism of the male body. Those tendencies started to influence the visual culture of Poland only in the 1990’s, mainly in advertising and then in the arts. Together with the influence of Western pop culture, the gay movement and its erotic products began to penetrate the visual sphere of the country only after the fall of Communism in 1989. The erotic frenzy of 1970’s America and Western Europe never happened here, so the first appearance of homoerotic art occurred when the AIDS epidemic was already well underway. (Indeed the first mention of homosexuality in mainstream Polish newspapers was in the context of AIDS.) Consequently, the Poles’ first glimpse of homoerotic art emerged in an exhibition about bodily and sexual fears and anxieties.

The works of art discussed here are located between two poles, as it were. On the one hand, there is critical art engaged in the social field, on the other, private erotic expressions. Both involve the representation of homoeroticism in public institutions and spaces, forcing the controversial subject of homosexuality into the arena of public discussion and thereby breaking a long silence. The presence of homoerotic art serves as a sign of a Polish culture in transition. As such, it offers a window on the state of democracy in Poland, on the advancement of Europeanization, and on the limits of artistic freedom.

Still, Poles are divided over whether the arrival of homoerotic art is a sign of progress and development or instead of crisis and collapse. Or perhaps it is just a fashion or an ideology. But it is precisely this tension that gives homoerotic art its energy and power as an element in the nation’s cultural avant-garde. This is true not only in Poland but in Eastern Europe in general, since the subject of homoerotic love is still politically charged, unresolved, risky to talk about, and (for that reason) commercially unspoiled.

Pawel Leszkowicz is an art critic and lecturer in contemporary art at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland.