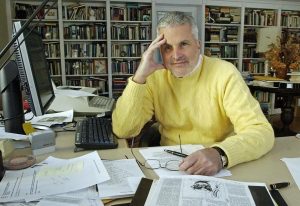

J.D. (“SANDY”) MCCLATCHY was so energetic, so ubiquitous, so generous with his time and talent that it’s hard to imagine that this star, this constellation, is now extinct. For years he was the editor of The Yale Review, the chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, the president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the editor of the great James Merrill’s papers, a prolific and inspired poet, the author of many libretti, including the New York City Opera’s hit Emmeline and Ned Rorem’s adaptation of Our Town. He wrote books on Anne Sexton, put together a glossy book about writers’ houses, and edited anthologies of love poetry, including Love Speaks Its Name: Gay and Lesbian Love Poems. He also translated the subtitles for many operas at the Met. (The last time I saw him was recently at the Met between acts of Rossini’s Semiramide, which he’d subtitled.) He famously shortened and translated the libretto for Julie Taymor’s whimsical production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute for children.

He was such a dear man, so witty, so gifted. He was a foul-weather friend who’d take care of everyone in need. Too funny to be sentimental, he was modest in his kindness. Erudite, sexy, magisterial, he resembled an older generation of genius poets (James Merrill, John Hollander, Richard Howard) more than his dumbed-down contemporaries. He translated Horace, turned his own life into great poetry, entertained with style and joie de vivre, remembered every name, never indulged others nor himself, had his portrait painted by Philip Pearlstein, was one of the last cultured New Yorkers. And a wonderfully encouraging force in the world of the arts.

I liked him because he liked me (does that sound too narcissistic?). He pretended he lusted after me when I was young and presentable. When I outed Merrill in The Farewell Symphony as someone who died of AIDS, he defended me against all the deniers. He liked my books, though he preferred my articles in various shelter magazines.

I met him through Alfred Corn, the great poe, and his longtime friend. For years Sandy and his husband Chip Kidd were one of the most prominent power couples in gay New York. Chip is the country’s leading book designer—always dashing off to conferences in Japan, universally honored for his innovative work—a novelist, a publisher, and the author of books of images about Batman and Superman. He and Sandy did everything to perfection—designed their New York apartments, their house in Stonington, Connecticut, their condo in Palm Beach. They were always beautifully dressed, alive with the latest gossip, true insiders, but miraculously modest. Sandy was invariably alert to absurdity and pretension, including his own, but nourishing to dozens of young poets and critics and novelists, including Henri Cole and Michael Carroll. He always had a new poem—thematically outrageous, formally conservative—on the hob, whether he was writing about his own mammogram or his radiation therapy. He was the brightest—the most cultured, the most inventive, the most door-opening—person our culture has been able to offer.

Edmund White’s latest book is titled The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading (Bloomsbury).