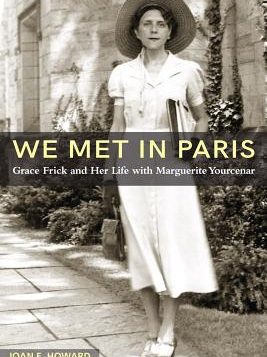

We Met in Paris: Grace Frick and Her Life with Marguerite Yourcenar

We Met in Paris: Grace Frick and Her Life with Marguerite Yourcenar

by Joan E. Howard

U. of Missouri Press. 468 pages, $45.

“MAJOR lesbian biographies” is a short roster of books. Lesbian subjects have been largely erased from history. Consequently, often in the past, and even today, the biographer’s task is made all the more difficult by the subjects themselves, their executors, and their gatekeepers. Tackling erasure requires a special kind of courage and dedication on the part of the biographer, as I discovered in restoring the life of Romaine Brooks. Joan Howard joins this distinguished sisterhood with We Met in Paris.

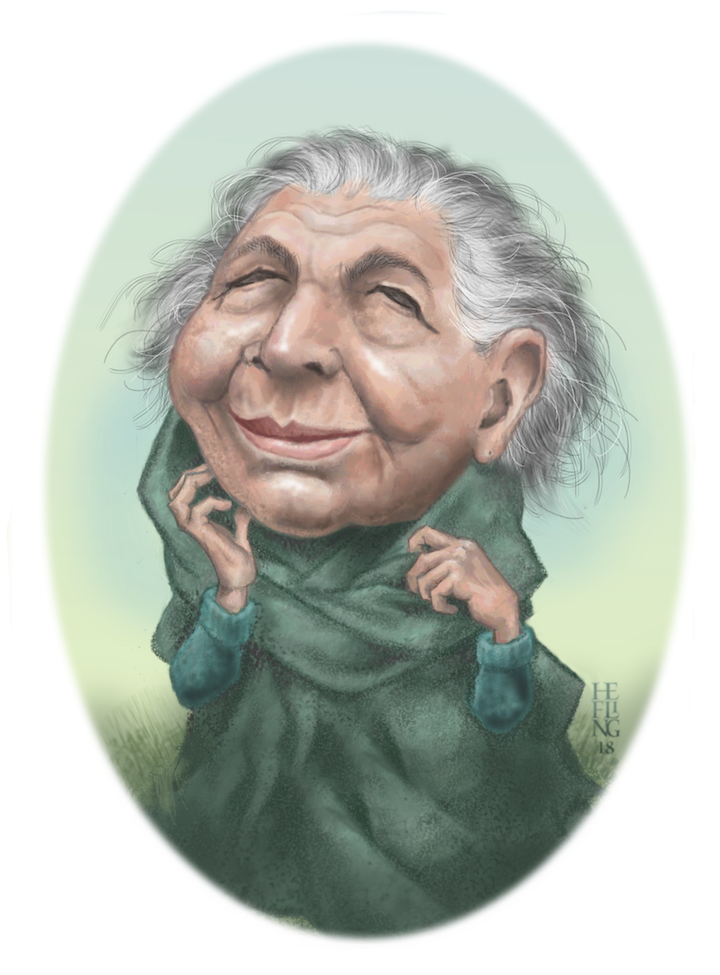

Howard’s labor of love recasts the relationship between writer Marguerite Yourcenar (1903–1987) and her lover, editor, and translator, Grace Marion Frick (1903–1979). When they met in Paris during the winter of 1937, Frick was an intrepid PhD student at Yale, struggling with her dissertation on the 19th-century English poet George Meredith. Yourcenar was a budding genius, a rising star on the French literary scene, with two novels published to critical acclaim. They were both staying at the Hôtel de Wagram, Yourcenar’s base of operations. Frick interrupted Yourcenar to introduce herself. They landed in bed together the next day. They were tinder and flint, as Vita Sackville-West once described her relationship with Virginia Woolf. Yourcenar didn’t want it to end, and on September 18th, she followed Frick to America, where she remained for the next 41 years.

They were a happy couple for most of their life together. If Yourcenar suffered from displacement, as some have claimed, it certainly wasn’t evident when she applied for American citizenship in 1942. Yourcenar mingled with no notable writers, it seems. She wrote in French. Frick edited every manuscript that left the house and translated Yourcenar’s work into English. They shared the cooking—and of course they composted.

Howard’s biography tells the story of their professional and domestic life at Petite Plaisance in Northeast Harbor, Maine, on a remote island far away from artistic currents. Their self-imposed isolation produced a literary masterpiece, Memoirs of Hadrian (1951). Still in print, this book is as politically significant today as it was in the aftermath of two world wars. Howard’s book precedes a flurry of new projects about Yourcenar and Hadrian, including a new opera by Rufus Wainwright that’s scheduled to open in Toronto in October.

Memoirs of Hadrian won Yourcenar her place among the immortals as the first woman admitted to the Académie Française in 1980. It was an honor Frick longed to share but never lived to savor. She died before the investiture, following a harrowing battle with breast cancer that Howard’s book documents in gruesome detail.

Memoirs of Hadrian won Yourcenar her place among the immortals as the first woman admitted to the Académie Française in 1980. It was an honor Frick longed to share but never lived to savor. She died before the investiture, following a harrowing battle with breast cancer that Howard’s book documents in gruesome detail.

Grace Frick grew up poor, in Toledo. She was orphaned at fifteen and taken in by well-to-do relatives in Kansas City. She graduated from Wellesley College in 1927 with a master’s degree. Academic distinction was critical for Frick’s job prospects. Her professors described her as “excellent with good executive ability, high ideals of scholarship and conduct, imagination and quick sympathy, much ingenuity, and a keen sense of humor.” And, one may add: a spirit of adventure that served the couple well in their travels and tribulations.

Frick loved to travel, and she never failed to remind people that they had met in Paris, which was the center of the literary and artistic world, and Ground Zero for lesbian celebrity couples. It was where they stayed for at least part of the year just to keep up-to-date. But Frick and Yourcenar were not a typical lesbian couple in this respect. Just why is what makes this book so interesting.

Money was a problem in their early years. Yourcenar, of noble birth, fled her native Belgium in World War I. She wasn’t able to recover any of her family wealth until middle age. To pay the bills, Frick abandoned her dissertation and secured jobs teaching languages at various American colleges. In 1940, Frick was appointed the second academic dean at Hartford Junior College, a two-year private school for women. Despite Frick’s energy, dedication, and organizational skills, she was fired two years later by the board of trustees. Bigotry was the unstated reason. Frick and Yourcenar made no secret of living together as a couple. Fortunately, Yourcenar had obtained a job teaching French at Sarah Lawrence College. Frick’s uncle died, leaving her a modest fortune that allowed them to buy a small house by the sea in the setting they loved on Mt. Desert Island. It was a brutal commute for Yourcenar, who didn’t drive. But it was worth it for two naturalists who became forerunners of today’s organic lifestyle.

Yourcenar continued to write and lecture. At least one avant-garde experiment left them bruised. In 1942, their bisexual Hartford friend Chick Austin produced one of Yourcenar’s plays at the Wadsworth Athenæum, where Austin was director. The following year, Austin was forced to take a leave of absence after producing John Ford’s incestuous play, Tis Pity She’s a Whore. Leaving his wife was the final scandal that got him sacked. Guilty by association, Yourcenar had become a target of anti-communist politicians bent on suppressing homosexuality.

Senator Joe McCarthy explicitly aligned homosexuality with communism, declaring both to be subversive of American values. By 1954, McCarthyism was in full swing when Yourcenar’s citizenship began to be challenged in a series of harrowing passport nightmares. The couple retreated to the relative safety of Northeast Harbor, where they were mostly welcomed into the live-and-let-live community. By 1951, Frick was freelancing as a “literary research assistant.” Memoirs of Hadrian, published that year, finally brought them undreamed-of financial success.

Contrary to what previous biographers have claimed, Howard argues persuasively that Yourcenar now had enough money to escape back to France had the relationship run its course. Howard’s careful research serves as a corrective to this and other inaccurate claims. For instance, to explain why Yourcenar veered away from “female subject matter,” previous biographers have shied from the obvious answer: ambition. Yourcenar wanted to be taken seriously by the literary establishment in France and America. Instead, biographers traced Yourcenar’s obsession with gay male protagonists to a seven-year, unrequited passion for her gay French editor that supposedly shadowed her for life. Howard’s research suggests that Yourcenar’s misguided heterosexual affair was a reality, not a fantasy—with Greek shipping heir Andreas Embiricos, a student of psychoanalysis during his years with Yourcenar.

The best passages in Howard’s book flesh out our understanding of Frick’s place in Yourcenar’s life, and vice versa. Frick seems to have recognized that the death of Yourcenar’s mother ten days after her birth traumatized Yourcenar and made her feel like a lost and lonely child all her life. Yourcenar became a source of inspiration and a fixation for Frick, who devoted her life to her. Credit Grace Frick, the managing partner, with forging their shared mission. The bold, brash American fascinated and attracted Yourcenar. Frick was cool, intellectual, outspoken, and politically active, making no bones about her lesbianism, but not flaunting it. Their day books reveal the negotiated differences that kept the original spark burning.

What’s puzzling is why, at the end of her life, Yourcenar was at such pains to downplay Frick’s centrality to her work. They were clearly collaborators. Yet in various interviews Yourcenar gave at the end of her life, she belittled Frick’s contributions to her work. Indeed there is early evidence of ambivalence about Frick’s role in her work. Only after Memoirs of Hadrian had become a bestseller did Yourcenar acknowledge Frick’s contributions in print: “Although Hadrian bears no dedication, it ought to have been dedicated to G.F.”

At the close of Howard’s book, there remains the unsolved enigma of their relationship. Why did this ambitious power couple, with all the means necessary to capitalize on the international success of Memoirs of Hadrian, fail to become cultural influencers? And, most worrying for those who want Yourcenar’s work to stay relevant to new generations, why did she disable scholars and intimates like Joan Howard by embargoing her private correspondence until 2037?

Marguerite Yourcenar and Grace Frick share a grave in Northeast Harbor, Maine. From there, it’s only a short walk to the shore where visitors can still look out over Somes Sound and contemplate the ever-constant, yet fluctuating, ripples of this pair’s life together.

Cassandra Langer, a freelance writer based in New York City, is the author of Romaine Brooks: A Life (Wisconsin).