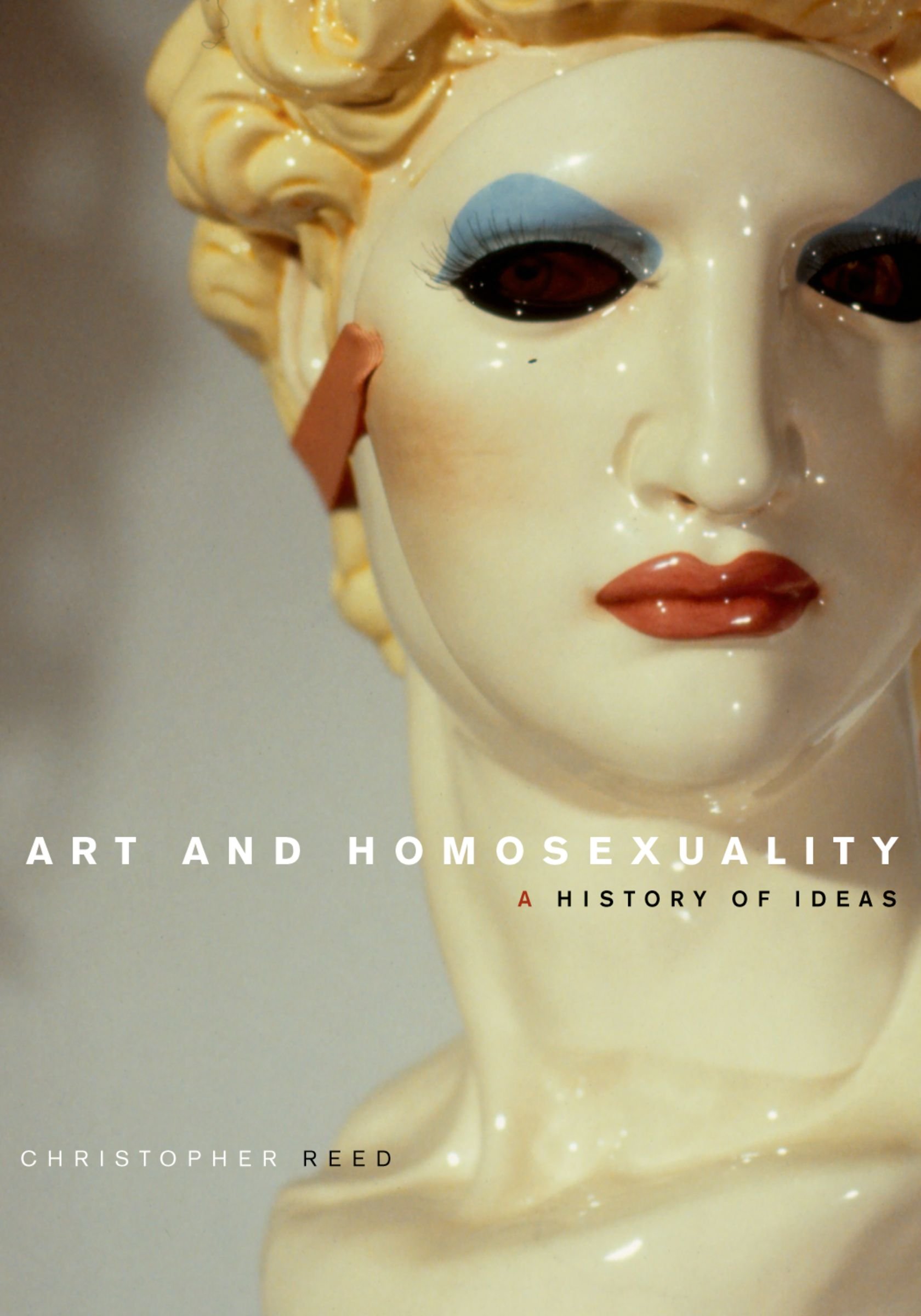

Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas

by Christopher Reed

Oxford Univ. Press. 304 pages, $39.95

“CALLING SOMEONE ‘arty’ or ‘artistic’ has often been a euphemism for homosexuality, and political debates about homosexuality have often played out as arguments about images.” So begins Christopher Reed’s inquiry into why these relationships between art and homosexuality have persisted and flourished in the modern era. Reed’s provocative and beautifully illustrated book may seem like another effort to define a history of homosexual art, following such influential works as Emmanuel Cooper’s The Sexual Perspective: Homosexuality and Art in the Last 100 Years in the West, James Saslow’s Pictures and Passions: A History of Homosexuality in the Visual Arts, and Harmony Hammond’s Lesbian Art in America, to name a few. But Reed takes a different path in his account, questioning how a history of homosexual art homogenizes more than illuminates. This book hinges on the argument that the story of homosexual art is not simply a history of objects and persons, but rather a complex story of cultural ideas about art and homosexuality that have changed across time and place. While we may connect artistic tendencies with homosexual ones today, this was not always the case.

It is an ambitious project, for the book covers a large swath of history and spans the globe, encompassing early Greek vases, Tokugawa-era Japanese prints, 19th-century French Romantic paintings, American abstract expressionist canvases, and Native American  woven prints. This schematic collection of objects is heavily anchored in American artists and works (particularly in the latter half of the book) so that, despite its gesture toward globalism, the book lacks depth in considering the social meanings of non-Western homoerotic art. This limitation does not, however, take away from Reed’s imaginative reconsideration of the varied intersections between art and homosexuality.

woven prints. This schematic collection of objects is heavily anchored in American artists and works (particularly in the latter half of the book) so that, despite its gesture toward globalism, the book lacks depth in considering the social meanings of non-Western homoerotic art. This limitation does not, however, take away from Reed’s imaginative reconsideration of the varied intersections between art and homosexuality.

Consider Reed’s interpretation of Michelangelo’s David. While an iconic artifact in the history of homosexual art, the statue was initially interpreted as a powerful image of Florentine power and influence. Florence was the epicenter of the early Renaissance, and David reflected “the Florentine elite’s vision of their city as the inheritor of Athenian ideals, including a Greek appreciation for masculine beauty.” This is not to deny the statue’s erotic meanings, only to suggest that we need to be cautious about celebrating the David’s homoerotic appeal based on contemporary notions. To understand a history of homosexual art is to grapple with the complicated ways in which homoeroticism has been tied to, or detached from, a particular culture’s definitions of what constitutes art.

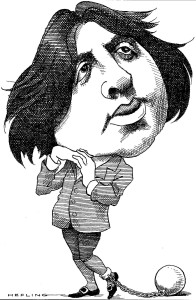

It was the emergence of Æstheticism in the 19th century that planted the seeds of our contemporary connection between “the artist” and homosexuality. The circle of Anglo-American women artists clustered around Harriet Hosmer in Rome in the 1860’s, for example, found success within the male-dominated art form. Hosmer, who called her circle of female friends the “jolly bachelors,” advocated, in Reed’s words, an “active rejection of heterosexual imperatives” as crucial for the professional success of a female artist. Hosmer and those in her circle used her status as a professional artist to question the gender and sexual norms of the era. Then of course there was Oscar Wilde, dedicated as he was to the idea of turning life into art and art into life, who ended up living out a certain archetype of the suffering homosexual artist, even as his writings had sharpened the image of the artist as a wit and a dandy. Reed contends that the long-term effect of the Wilde trial was to make “æstheticism the ‘look’ of homosexuality, and thus a touchstone in the emergence of gay subcultures, for decades to come.”

Nevertheless, the backlash against Wilde would haunt the work of many avant-garde artists in much of the 20th century. Reed offers a critique of the avant-garde in the early century, pointing out that, while Modernism is seen as a rebellion against middle-class æsthetic notions, it also embedded a homophobia that marginalized many artists, notably Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth, and Duncan Grant, whose paintings of homoerotic themes were often rejected by avant-garde artists and critics. Reed argues intriguingly that the notion of homosexuality as a personal secret was integral to the avant-garde: “Homosexuality, inscribed by sexology as the secret status of the artist as a ‘type,’ became the paradigmatic secret of avant-garde art. Its status as an ‘open secret’—constantly suspected and hinted at, but never frankly acknowledged—is one of the defining characteristics of the modernist avant-garde.”

This thread of secrecy is present in the abstract expressionists of the 1940’s and 1950’s, exemplified by Jackson Pollock’s exaggerated heterosexual masculinity in both his art and his public persona. At the same time, some gay artists reimagined the relationship between art and homosexuality, infusing their art with a resistance to critical demands of the time. Francis Bacon’s use of eroticized Physique Pictorial images and Andy Warhol’s pop art and camp æsthetic questioned not only the definition of “art” but also the avant-garde’s attitude toward homosexuality.

Art in the AIDS crisis came to define homosexual anger and rage in a way that was politically engaged and sexually explicit. Artists were at the center of the culture wars of the 1980’s, as witness the battles over Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, which became a rallying cry for conservatives. Nor has this controversy gone away entirely even today. Late in 2010, an exhibition called Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in Portraiture opened at the National Portrait Gallery. Conservative groups and politicians forced the gallery directors to remove an AIDS-inspired video installation by David Wojnarowicz titled “Fire in the Belly.” Still, as curator Jonathan Katz noted in an interview in this magazine (March-April 2011), the very fact that gay art is being presented as an overlooked genre at the Smithsonian would seem to be a sign of progress.

Where might this progress lead us? Reed’s book concludes with the lesson that “definitions are dependent and dynamic.” This falls quite flat and was a disappointment in a book rich with historical insights. But despite these last few pages, Art and Homosexuality provides a useful rethinking of the history of our art and ourselves.

James Polchin teaches writing at NYU, writes a visual arts column at TheSmartSet.com, and edits the website WritinginPublic.com.