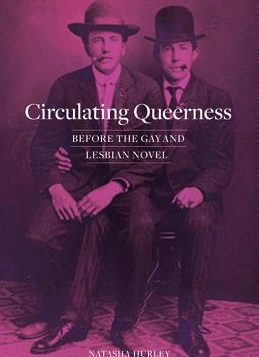

Circulating Queerness: Before the Gay and Lesbian Novel

Circulating Queerness: Before the Gay and Lesbian Novel

by Natasha Hurley

University of Minnesota Press. 320 page, $27.

WHERE DID today’s gay novel come from? Did it spring Athena-like fully armed from the mind of its authors? In her fascinating, adroit, but at times maddeningly opaque second book of queer studies, Natasha Hurley aims to answer these questions. In five dense, far-ranging chapters, she traces the emergence of the gay novel. Hurley argues that what we now identify as the overt gay or lesbian novel grew out of earlier literary productions, ones that contributed to the “making of selves and sentences, sympathies and worlds that [had]not yet existed.”

Protagonists whom we would now identify as queer, lesbian, gay, or bisexual often first showed up in literature as spinsters, eccentrics, and chums—characters defined “not by their inner sympathies at all but by their locations.” These locations, whether the hyper-sexualized South Sea Islands or the drawing rooms of unmarried Boston ladies, came to signal the possibility of complex, fully realized homosexual lives. Hurley rejects the notion that these early works were examples of “closeted writing.” Instead, she argues for a more nuanced approach, examining the conditions that made way for the homosexual novel. The case studies she considers are ones which, she argues, anticipate in a variety of ways the explicit gay and lesbian novel.

Melville’s novel Typee (1846)—a text with an “acquired queerness” that was not legible to its first audience—is a case in point. The social world of the novel’s South Seas location, with its unflinchingly steamy descriptive detail, helped the book gain a wide and appreciative audience. Over time, Typee—the most successful book Melville ever published—came to seem queer to some of its readers. At what point in its reading history this occurred is not clear, but Melville’s refusal to condemn the same-sex affection depicted in the novel opened up possibilities “for readers to see a glimmer of license for sexual relationships between men.” By the 20th century, Melville had emerged as an inspiration—Hurley calls it a “persistent presence”—in the imaginations of gay writers like Hart Crane, Robert Duncan, and Tennessee Williams.

The focus of Hurley’s second chapter is a little-known writer named Charles Warren Stoddard. Stoddard maintained a robust correspondence with virtually every major literary figure of his time. His letters are, she says, “an astonishing reflection of the ways the American publishing industry at the end of the nineteenth century was both created and reflected through sexual relationships between men.”

Hurley next turns her attention to the appearance of “the old maid” in late 18th- and 19th-century American literature. In stories and novels by Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sarah Orne Jewett, and Edith Wharton, this stock type—a “historically distinct figure, not a lesbian euphemism”—began to be seen in more complex ways that made it possible for readers to imagine another type of unmarried woman, the lesbian. The evolution of the old maid literary type is consolidated in one late 19th-century novel, Henry James’ The Bostonians. Although James never set out to write a lesbian novel per se, his careful attention to the lives of the novel’s two main female characters, Olive Chancellor and Verena Tarrant, emphasizes the existence and in fact the centrality of these relationships in American society.

Once it became possible for American readers to imagine same-sex relationships, a shift took place in American letters. By the end of the 19th century, authors were testing the possibility of novels with fully developed queer protagonists. While the overtly homosexual novel was still some years away, nevertheless an author like Sarah Orne Jewett could produce a short story like “Martha’s Lady,” which, she noted in 1897, one could read “joyfully between the lines.” Two decades later, Henry Blake Fuller would come out—in bothsenses of that phrase!—with Bertram Cope’s Year(1919), an unambiguously gay novel, and one “mobilized by fascination with queer life.”

Hurley, an associate professor of English at the University of Alberta, is not immune to the virus of postmodern jargon. While the lay reader will find much of this book quite readable, too many sentences creep into her prose that this reader found inscrutable. What, for instance, does one make of a sentence like this: “Fictions of queer life (environmentally, temporally, romantically, and psychically) come more fully into view as a life narrative, subject to change over time, as fictional episodes are positioned alongside each other and in sequence, if not in series—all while the homosexual as a sexological and psychological type is becoming a species.” There is so much worth serious consideration in Hurley’s book, but sentences like that one—alas, not a lone example—at times make her literary sleuthing a very murky affair.

_____________________________________________________________

Philip Gambone is a regular contributor to this magazine.