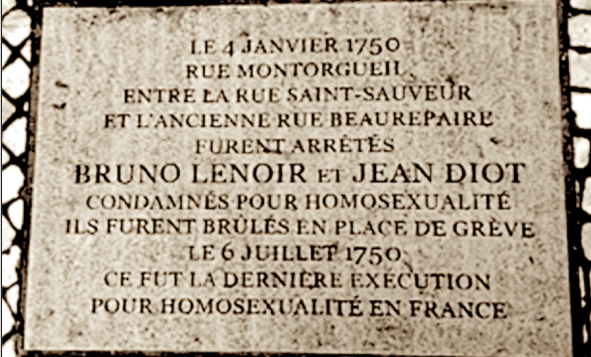

IF YOU HAVE VISITED Paris in the last five years, you may have seen a plaque embedded in the pavement in the pedestrianized blocks of rue Montorgueil that commemorates Bruno Lenoir and Jean Diot, the last men executed for sodomy (not homosexuality, as the inscription indicates) in France, on 6 July 1750. This plaque has undoubtedly provoked not only horror and sorrow but also questions in the minds of natives and tourists alike. How many others were burned at the stake for this crime with or (in this case) without aggravating circumstances such as blasphemy and violence? Did the prosecution of these two men constitute a turning point in the history of repression, decades before the decriminalization of pederasty during the Revolution? What do we know about Lenoir and Diot and other workingmen, as well as noblemen and clergymen, involved in same-sex relations at this time and place?

The answers to these questions lie in several archival collections that include thousands of relevant documents from the years 1715 to 1765 and hundreds more from the 1780s. Michel Rey (1953-93) explored some of the sources in a series of articles published decades ago. Other historians, more in this country than in France, have continued this research.* We are currently digesting abundant but incomplete information about the profiles and networks of men the police called “sodomites” (from the name of the city destroyed by fire in Genesis 19) before 1750 and “pederasts” (from the Greek words for love of boys) after that year. We are processing surprises and revising conclusions as we proceed. A database under construction at Colorado College, which may contain as many as 10,000 names in the end, will allow us to analyze age, status, origins and addresses, proclivities, and activities more systematically in the future than has been possible in the past. The project website will include background essays (my topics thus far include dogs, friendship, and suicide), an introduction to archival resources, a comprehensive bibliography, and many other features.

The answers to these questions lie in several archival collections that include thousands of relevant documents from the years 1715 to 1765 and hundreds more from the 1780s. Michel Rey (1953-93) explored some of the sources in a series of articles published decades ago. Other historians, more in this country than in France, have continued this research.* We are currently digesting abundant but incomplete information about the profiles and networks of men the police called “sodomites” (from the name of the city destroyed by fire in Genesis 19) before 1750 and “pederasts” (from the Greek words for love of boys) after that year. We are processing surprises and revising conclusions as we proceed. A database under construction at Colorado College, which may contain as many as 10,000 names in the end, will allow us to analyze age, status, origins and addresses, proclivities, and activities more systematically in the future than has been possible in the past. The project website will include background essays (my topics thus far include dogs, friendship, and suicide), an introduction to archival resources, a comprehensive bibliography, and many other features.

Records of surveillance, entrapment, arrest, interrogation, imprisonment, and occasional prosecution provide the only access we have to the heads, hearts, and hands of the flesh-and-blood men (as opposed to fictional characters) who desired men in 18th-century Paris. (Women who desired women did not seek them in public spaces under surveillance, so we know almost nothing about them.) This modest essay has a single but not simple objective, which is to consider the ways in which the extant sources allow us to hear their voices, in the first or third person.

We do not know, for example, what one Lenoir, age twenty or 21, a cobbler’s assistant, and Diot, forty, a domestic servant turned day laborer, said to each other in rue Montorgeuil after 11 pm on 4 January 1750. But thanks to the unpublished judicial proceedings, we do know what they said, or at least some of what they said, to the sergeant of the guardsmen who arrested them in the act, to the district police commissaire who consigned them to prison, and to the magistrates who interrogated them more than once. Both men denied the charges and, without lawyers to advise them, reworked their stories in the course of January. Lenoir reported that Diot had “importuned” him but later testified that he had been inebriated and did not remember anything. Diot asserted that he had tried to help the drunken workman but later insisted that he had been alone at the site on the night in question. As this case suggests, men in custody had more reason to defend themselves than to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth to officers, commissaires, or magistrates, who chastised more than a few of them for lying.

Men spoke more freely during other types of encounters, which generated different sorts of documents. The Archives de la Bastille contain hundreds of reports of conversations between “sodomites” and police decoys in public spaces such as the Luxembourg and Tuileries gardens. The reports include many of the same comments and gestures, as well as numerous variants in their opening lines. Thus, for example: Charles Gentil accosted a man listening to music emanating from the Tuileries palace by noting that “there are some fine instruments in this ensemble” and adding that “there are others that do not make so much noise but give more pleasure” (from the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Archives de la Bastille, November 1, 1728). He explained by exposing himself, as countless others did without the clever verbal prelude. Many “sodomites” discussed their endowments or endurance, preferences and adventures, all in order to impress and entice the object of their desires. Some declared that they had never liked women (sometimes in misogynistic terminology) and always liked men—which begins to sound like an assertion of personal sexual identity.

But not so fast. The reports in question are not transcripts but accounts composed after entrapment, in which decoys recalled what “sodomites” had said and done, in greater or lesser detail. Some agents recorded several pages of dialogue, but others summarized all the words exchanged during the game of seduction and deception as the usual “nonsense.” We do not know for sure how many of these men made authentic or formulaic remarks about women versus men. Judging from the sources, more attributed their taste for men to the experience of “corruption” by someone else, whether years, months, or weeks before the arrest. In any event, “sodomites” on the prowl performed in the gardens, with their voices and bodies, to close the deal. Some prevaricated, for example, about their marital status, and more exaggerated about their assets and sexual exploits. It is significant that some accused sodomites thought that a lifelong aversion for women made them more desirable. At the same time statements about a lifelong attraction to men cannot be taken as a transparent marker of a distinctive sense of identity on the part of the minority who made them, let alone the majority who did not.

Around 1750, the police interrogated individuals implicated by men under arrest much more systematically than before. Few of the depositions, which constitute condensed sexual autobiographies, include incriminating declarations about lifelong attraction. Most of them include exculpatory revelations about the insiders and outsiders in the lives of the deponents who had “corrupted” them. Jean Baron, age 24, a valet, admitted that he had masturbated “frequently” with comrades ten years before and “contracted an inclination for this vice, which he has not been able to correct himself of thus far” (January 20, 1750). Some of the depositions include accounts of assemblies of accused “sodomites” (in which men dressed and talked like women) or expressions of repentance, which does not mean that the men did not attend such gatherings or confess their misconduct before or after.

By the 1780s, the police did not employ decoys or question prisoners as routinely as in the past. Reports of arrest during this decade contain few conversations, few interrogations, and therefore less information in their own words about what “pederasts” said and did. Over the course of the century, changes in methods of surveillance and detention dictated changes in recorded evidence, which do not, in and of themselves, demonstrate changes in behaviors and attitudes. It does not make sense to assume that men in the 1720s had more self-consciousness of sexual difference than men in the 1780s did. It does make sense to read every record with the circumstances and objectives that shaped it in mind, without making “sodomites” and “pederasts” sound more modern than they were or indeed could have been. We need to consider what they said, as well as what they did not say, and how and why they said it, before we assume we know what they meant.

Archival documents provide more access to voices in public spaces, in the Luxembourg and Tuileries or in custody, than in private places not subject to regular surveillance. We know that “sodomites” met friends and had sex in taverns and the furnished rooms they rented in boardinghouses, as well as the residences of men of rank or means, who often employed the services of procurers. We know more about their outer than inner lives, so I was astonished to discover three undated, handwritten notes in the dossier of Louis Malisset, age 22 or 23, tall, handsome, effeminate, a former lackey, who reportedly “corrupts young folks in order to place them” as servants “with folks of the taste of sodomy” (April 28, 1733). In one note, he used the informal “you” (tu) in acknowledging receipt of a letter from “my dear friend” (grammatically male) and the formal “you” (vous) in designating himself “your servant.” In between, he expressed gratitude for the friend’s “attentions,” and added: “I will try to deserve them more from now on than I did in the past.” The friend might be the unnamed benefactor who supposedly paid him an annual pension until he learned that Malisset “associated with too many people.” Two notes in a different hand and more proper French, presumably written to rather than by Malisset, deserve to be quoted in full:

Is it possible, my dear friend, that in this Paris where I felt the first effects of your kindness, where I had so often the pleasure of being close to you, we are now so far apart. I would be dead from sorrow already if the pleasure of seeing you again did not protect me from my worries. But alas, what can this pleasure delight me with because I am on the point of losing you despite all I have done to protect myself from it.

Farewell, my dear. I do not have the time to say anything to you, so tell yourself, from me, all the tenderest things you can imagine, and perhaps you will still fall quite far short of what I feel.

We do not know what happened to separate the two men, but, despite the formal “you,” they certainly sound like more than “just friends,” and the police assumed as much. With any luck we will find more such texts to remind us that men could and did voice affection for each other long ago.

* For more on Rey’s work and research in progress, see Jeffrey Merrick, “Patterns and Concepts in the Sodomitical Subculture of Eighteenth-Century Paris,” in the Journal of Social History50.2, 2016; and “New Sources and Questions for Research on Sexual Relations between Men in Eighteenth-Century France,” in Gender & History30.1, 2018.

Jeffrey Merrick, professor of history emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, is the author of Sodomites, Pederasts, and Tribades: A Documentary History of Same-Sex Relations in Eighteenth-Century France(Penn State, 2019).